Signs of Life

Last year we bought a young cherry tree to replace an acer that had died in the first year of the pandeic, possibly because we hadn’t reckoned with the very dry Spring. So we have and watched over its successor like a pair of anxious parents. Yesterday morning I went out to check on it and photographed the top of one of its branches, relieved by the realisation that it is clearly ok.

Later, looking again at the photograph, I find myself marvelling at how good the camera in the iPhone 11 is. I’m a serious photographer and usually bring a Leica with me when we go walking. But, even then, I sometimes find that the iPhone produces better pictures. And, of course, the old adage — that the best camera is always the one you happen to have with you — applies with increasing force. Apple’s decision to pour astonishing amounts of resource and technical talent into the iPhone camera has clearly paid off.

Quote of the Day

The Prime Minister made much the same false statement to parliament on 24 Nov, 5 Jan, 12 Jan and 2 Feb. @FullFact have repeatedly requested a correction and the Office for Statistics Regulation have written to his office to ask him to stop. The claim is important in its own right (it’s that there are hundreds of thousands more people in employment now than before the pandemic; in fact there are hundreds of thousands less) but the principle is important too. You can be thrown out of the House of Commons for accusing someone of lying – but not, it seems, for repeatedly making untrue statements?

Tim Harford, on his blog

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Chet Atkins and Mark Knopfler | I Still Can’t Say Goodbye

Link

It’s nice the way it steals up and grabs you.

Long Read of the Day

What Was the TED Talk?

An insightful assessment by Oscar Schwartz of the TED-talk phenomenon and the story about our future(s) that it’s been subliminally pushing over recent decades and which, Schwartz thinks, “has contributed to our unending present crisis”.

The story goes like this: there are problems in the world that make the future a scary prospect. Fortunately, though, there are solutions to each of these problems, and the solutions have been formulated by extremely smart, tech-adjacent people. For their ideas to become realities, they merely need to be articulated and spread as widely as possible. And the best way to spread ideas is through stories — hence Gates’s opening anecdote about the barrel. In other words, in the TED episteme, the function of a story isn’t to transform via metaphor or indirection, but to actually manifest a new world. Stories about the future create the future. Or as Chris Anderson, TED’s longtime curator, puts it, “We live in an era where the best way to make a dent on the world… may be simply to stand up and say something.”

And yet, Schwartz maintains, TED’s archive is actually “a graveyard of ideas” an endlessly optimistic manifesto for futures that never materialised. So what happened to those futures?

It’s a great read, so the spoilers stop here.

But afterwards…

I came away with two thoughts.

One was that the interesting futures envisaged by the attractive solutionists on the TED stage didn’t come about because they seemed blissfully unaware of the realities of political, ideological and corporate power which are actually making sure that those futures never happened, or — if they did — happened under their supervision.

Another thought sparked by one striking passage:

Perhaps the most incisive critique came, ironically, at a 2013 TEDx conference. In “What’s Wrong with TED Talks?” media theorist Benjamin Bratton told a story about a friend of his, an astrophysicist, who gave a complex presentation on his research before a donor, hoping to secure funding. When he was finished, the donor decided to pass on the project. “I’m just not inspired,” he told the astrophysicist. “You should be more like Malcolm Gladwell.” Bratton was outraged. He felt that the rhetorical style TED helped popularize was “middlebrow megachurch infotainment,” and had begun to directly influence the type of intellectual work that could be undertaken. If the research wasn’t entertaining or moving, it was seen as somehow less valuable. TED’s influence on intellectual culture was “taking something with value and substance and coring it out so that it can be swallowed without chewing,” Bratton said. “This is not the solution to our most frightening problems — rather, this is one of our most frightening problems.”

I also liked Robert Cottrell’s assessment on his curated newsletter, The Browser.

He thought that Schwartz’s piece was,

an astute assessment of the impact that the TED Talk had on the cultural role of the public intellectual. No punches are pulled. At the height of its popularity, the “inspiresting” style of these speakers was reaching tens of millions. This mode is “earnest and contrived. It is smart but not quite intellectual, personal but not sincere, jokey but not funny. It is an aesthetic of populist elitism”

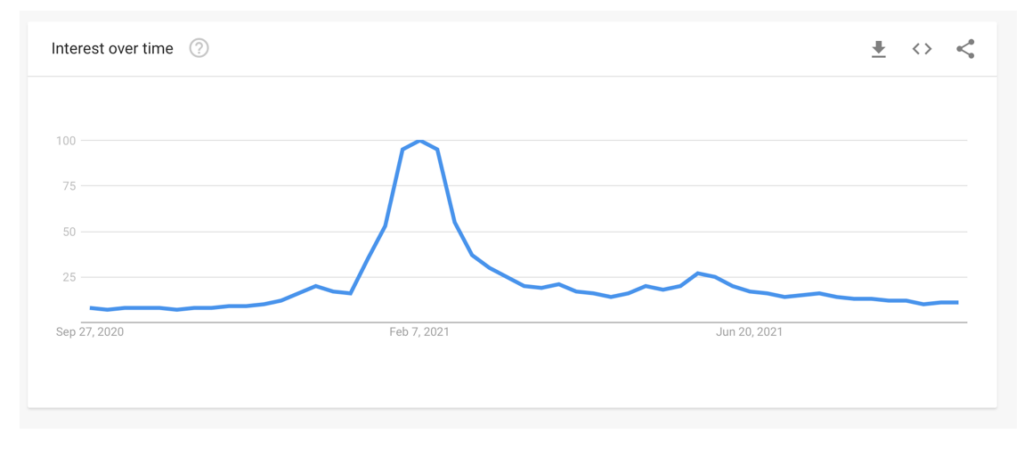

Has Facebook peaked?

My OpEd in last Sunday’s Observer:

Facebook was much in the news last week, although you may not realise that because it has been renamed Meta in the hope the bad vibes associated with its maiden name would gradually fade from public memory. (Google tried the same stunt with Alphabet and that hasn’t worked either.)

For a change, though, Facebook’s latest moment at the top of the news agenda had nothing to do with scandals and everything to do with its financial results, which were so unexpectedly bad that the shares dropped 25% at one point, taking $240bn (£177bn) off its market value, which in turn led to a 2% drop in the Nasdaq index.

Given that Facebook has hitherto been a licence to print money, so much so that at one stage (in 2019), when it was fined $5bn by the Federal Trade Commission, its shares actually went up as Wall Street registered that the ostensibly massive fine was actually the equivalent of a fleabite on an elephant.

But this time was different. Why? Three factors stood out from reports of Mark Zuckerberg’s conference call with stock market analysts: the impact of TikTok; Apple’s move to require iPhone users to consent to being tracked by advertisers; and the revelation that the hitherto unstoppable growth in the number of Facebook users has stalled…

Read on

Embracing George W?

Fabulous essay by Elayne Oliphant on meeting George W Bush at the ceremony where she became a US citizen.

Beforehand, I had told myself numerous stories about why I was pursuing American citizenship: the US had undeniably become home, I wanted to vote, I wanted to cross borders with the same passport as my children. To myself, however, I carefully avoided the question of whether or not I could obtain American citizenship—with relative ease as a white, cis-gendered, straight, professional, upper middle-class Canadian—without also engaging in American violence.

But now here I was, participating in a shocking display of televised propaganda, waving my tiny flag furiously as the camera swooped around us ahead of each commercial break. In the presence of George W. Bush, I uttered an oath in which I promised to forego all previous loyalties and be willing to “bear arms on behalf of the United States when required by the law.” It was a powerful and painful reminder that all of these elements—my family, my community, and American violence—cannot be disentangled.

Fascinating, nuanced piece.

My commonplace booklet

Testing the effectiveness of KN95 and surgical mask ‘fit hacks’. You’d be amazed what people do to try and improve the fit. Link