David Howarth, the former MP for Cambridge (and one of the few Members of Parliament to emerge with honour from the expenses scandal), at a CSaP seminar on Friday. He’s now resumed his academic career after standing down at the last election. His successor as MP, Julian Huppert, was an academic until he was elected.

Category Archives: Asides

Terminological inexactitude

I’ve long been struck by the way in which technological terms get corrupted (i.e. abbreviated) in common parlance. Thus “transistor radio” became “transistor”, and “videotape” (or “videocassette”) became “video”. The same thing is now happening to “blog post”. On Sunday I called on a friend who mentioned that he was “writing a blog” about something we were discussing when he clearly mean a blog post. And this morning I find that two eminent bloggers have slipped into the same usage — here and here.

Dearly beloved, I say unto you: The tipping point is near.

Juicy Toms

Want to pay lower interest rates on bonds? Get connected.

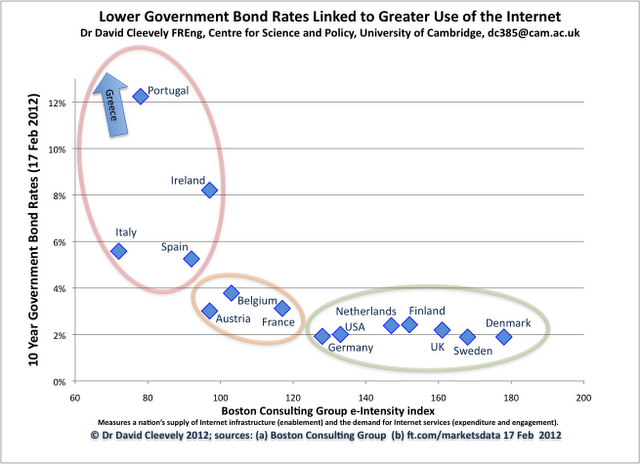

Sitting next to me at last week’s lecture by Simon Hampton of Google was David Cleevely who in addition to being a successful entrepreneur is also the Founding Director of the Cambridge Centre for Science and Policy. At one point, Simon put up a slide showing the percentage of GDP contributed by the Internet in a wide range of European countries. As the animation flashed by David whispered to me: “wonder if there’s a correlation between those percentages and bond yields?” After the lecture, he cycled off purposefully into the gathering gloom. I suspected that he was Up To Something.

He was. Yesterday he and his son Matthew (who’s currently doing a PhD at Imperial College Business School) published this chart on their blog.

They plotted 10-year governmental bond rates against the Boston Consulting Group’s measure of “e-intensity” for countries in the Eurozone group.

Member states which have not had the capacity to adopt and develop the internet and ecommerce are those with skyrocketing risk premiums on their governments’ debt. These states form a distinct group: Portugal, Italy, Spain, Ireland and Greece (which is literally off the scale) – all with high debt premiums and an e-Intensity score of well under 100.

There are two other groups: those with high e-Intensity and low government bond rates such as Germany, Denmark and the UK, and a middle group (Belgium, Austria and France) with lower e-Intensity (100-120) and raised bond rates of 3-4%.

David and Matthew see two possible (and possibly non-exclusive) explanations for this:

1. Low e-Intensity indicates underlying structural problems: countries with high e-Intensity are those which have invested in modern processes, improved productivity and benefit from strong institutions. These are the countries that have lower borrowing costs, as they are best placed to grow their economies in the future.

and/or

2. e-Intensity (or what it represents) is a fundamental capability: countries which use the internet intensively can respond more flexibly to shocks and crises, instead of being weighed down by cumbersome 20th century processes and institutions.

So…

if you can get a country to invest in, use, and compete on the internet, then you must have either eliminated or minimised any underlying structural problems, or created a flexible and robust economy, or both.

Policymakers, please note.

From web pages to bloatware

This morning’s Observer column.

In the beginning, webpages were simple pages of text marked up with some tags that would enable a browser to display them correctly. But that meant that the browser, not the designer, controlled how a page would look to the user, and there’s nothing that infuriates designers more than having someone (or something) determine the appearance of their work. So they embarked on a long, vigorous and ultimately successful campaign to exert the same kind of detailed control over the appearance of webpages as they did on their print counterparts – right down to the last pixel.

This had several consequences. Webpages began to look more attractive and, in some cases, became more user-friendly. They had pictures, video components, animations and colourful type in attractive fonts, and were easier on the eye than the staid, unimaginative pages of the early web. They began to resemble, in fact, pages in print magazines. And in order to make this possible, webpages ceased to be static text-objects fetched from a file store; instead, the server assembled each page on the fly, collecting its various graphic and other components from their various locations, and dispatching the whole caboodle in a stream to your browser, which then assembled them for your delectation.

All of which was nice and dandy. But there was a downside: webpages began to put on weight. Over the last decade, the size of web pages (measured in kilobytes) has more than septupled. From 2003 to 2011, the average web page grew from 93.7kB to over 679kB.

Quite a few good comments disagreeing with me. In the piece I mention how much I like Peter Norvig’s home page. Other favourite pages of mine include Aaron Sloman’s, Ross Anderson’s and Jon Crowcroft’s. In each case, what I like is the high signal-to-noise ratio.

How things change…

From Quentin’s blog.

There’s a piece in Business Insider based on an interesting fact first noted by MG Siegler. It’s this:

Apple’s iPhone business is bigger than Microsoft

Note, not Microsoft’s phone business. Not Windows. Not Office. But Microsoft’s entire business. Gosh.

As the article puts it:

The iPhone did not exist five years ago. And now it’s bigger than a company that, 15 years ago, was dragged into court and threatened with forcible break-up because it had amassed an unassailable and unthinkably profitable monopoly.

Wow! It seems only yesterday when Microsoft was the Evil Empire.

Regulating the Net

This evening I went to an interesting lecture on “The challenges of regulating the Internet” given by Simon Hampton, who is Google’s Director of Public Policy for Northern Europe. He was, he insisted, speaking only “in a personal capacity” and the audience, for the most part, took him at his word. His thesis was that in the technology business the greatest challenge is “the transition from scarcity to abundance” and that policy-makers haven’t taken this transition on board.

The metaphor he used to communicate abundance was the hoary story of the guy who invents the game of chess and who, when asked by the Emperor what he would like as a reward requests one grain of rice on the first square, two on the second, four on the third, etc. You know the story: according to Hampton by the time you get to the 64th square the amount of rice needed is the size of Everest. At which point my neighbour, David Cleevely, nudged me and said that he had worked it out and it was enough rice to cover the entire surface of the earth to a depth of nine inches! But it turned out that, for Hampton, the metaphor also has a chronological dimension: we’re just about half-way through the chessboard.

As befits someone who spends a lot of time in Brussels arguing with the anti-trust division of the European Commission, he has a pretty jaundiced view about what goes on there. But he made a good point, namely that the EU finds it easiest to regulate in new areas simply because regulating in existing areas means dealing with the reluctance of member states to change their existing laws. The result is that the Commission tends to to move too quickly to legislation (in the form of Directives) in emerging areas. Examples: the e-Money Directive; the e-Signature Directive; and, now, the Privacy Directive. Plus, of course, the idiocy of applying to the Net concepts designed for regulating TV broadcasters.

He then went on to list the four big companies that have “embraced abundance” — Apple, Amazon, Google and Facebook. They all operate on massive scale and have an interest in a bigger, freer Internet — though they have only recently woken up to the necessity of lobbying for this in the corridors of power (which is why the campaign against SOPA was so significant). In this context, Hampton claimed, size really matters — which is why moving into the second half of the chessboard is so significant. “The larger the haystack, the easier it is to find the needle.” (Not sure I followed his logic here.)

He was interesting on the subject of lobbying — which of course is a large part of his job and he defined it as trying to persuade legislators and policy-makers that their concept of the public interest should be realigned with those of industrial lobbies. People in declining industries tend to scream, and thereby gain public — and media and legislators’ — attention; in contrast, people in new, growing industries are too busy getting on with it — which probably explains why the big Internet companies were so slow to get their lobbying act together in Washington.

Finally, Hampton moved to the question of how to rethink policy-making in the context of abundance. In his opinion, there’s no need to change the broad objectives of public policy. The key switch that is needed is for policy-makers to “embrace abundance”.

What would that mean in practice? He suggested three general principles:

In the Q&A the main topics were (a) the cluelessness of legislators in relation to the Internet, and (b) concerns about privacy (hardly surprising given this). I made the point that legislators have always been clueless, so there’s nothing new here. (I quoted Bertrand Russell’s argument about why an MP couldn’t be more stupid than his constituents — “because the more stupid he is, the more stupid they are to elect him”.) The point is that in a representative democracy, Members of Parliament should not be expected to be knowledgeable about everything. It’s Parliament, as an institution, that needs to be knowledgeable — which is why we need evidence-based policy-making in relation to Internet regulation, intellectual property, etc. And, to date, we’ve had very little of that.

So the battle for an open Internet continues.

iMicroscope

The product ecosystem that surrounds Apple iDevices reminds me of the Peace of God as described in the Bible — in that “it passeth all understanding”. This is an add-on for the iPhone4 (and 4S) that turns it into a microscope.

Well, sort-of.

The only thing I could find to test it when it arrived was a penny. This is how it came out.

Somehow, I don’t think it’ll make me into a latter-day Leeuwenhoek. But it’s fun.

Telling it like it is

Just came on this in Aaron Sloman’s wonderful home page:

What should I write if asked to act as an academic referee, and the invitation requests me to assess the impact of the candidate’s work?

“I am not interested in impact, only quality of research, which does not always correlate with impact, since the latter is often subject to fashion and transient funding policies, etc. If you want a study of impact you would do better to consult a social scientist. Moreover high impact as measured by citations is often a consequence of making mistakes that many other people comment on.***

Many great research achievements could not possibly be assessed for their impact until many years later, in some cases long after the death of the researcher (e.g. Gregor Mendel).I’ll tell you what I think about the research quality: things like the depth, difficulty, and importance of the questions addressed, the originality, clarity, precision and explanatory power of the theories developed, and how well they fit known facts, as far as I can tell. If there are engineering products I may have some comments on their contribution to research. I shall not be able to evaluate their contribution to wealth or happiness.”

Thanks to Seb Schmoller for the link.

***Footnote: Really acute observation this. One of the most cited research papers in recent history is the infamous MMR paper published by the Lancet.

Consent of the Networked

I’ve just got Rebecca MacKinnon’s new book and am looking forward to reading it. But at the same time as it arrived I also got notification of her talk at the Boston launch of the book. It’s vintage MacKinnon: intelligent, informed, perceptive. I particularly like her concept of the “Sovereigns of Cyberspace” — Zuckerberg, Bezos, Page, Brin, Apple, Microsoft. I also like her use of the “information ecology” metaphor: we’ve moved from an ecosystem characterised by scarcity (a desert) to one characterised by abundance (a rain-forest) and the challenge is to devise a system of governance for that.

John Kampfner’s review is here.