Category Archives: Asides

How to do invective

From H.L. Mencken’s obit of William Jennings Bryan who was three times the Democratic candidate for President of the US, and the 41st Secretary of State but who was also a major opponent of Darwinism and a witness in the 1925 Scopes trial:

When I first encountered him, on the sidewalk in front of the office of the rustic lawyers who were his associates in the Scopes case, the trial was yet to begin, and so he was still expansive and amiable. I had printed in the Nation, a week or so before, an article arguing that the Tennessee anti-evolution law, whatever its wisdom, was at least constitutional – that the yahoos of the State had a clear right to have their progeny taught whatever they chose, and kept secure from whatever knowledge violated their superstitions. The old boy professed to be delighted with the argument, and gave the gaping bystanders to understand that I was a publicist of parts. Not to be outdone, I admired the preposterous country shirt that he wore – sleeveless and with the neck cut very low. We parted in the manner of two ambassadors.

But that was the last touch of amiability that I was destined to see in Bryan. The next day the battle joined and his face became hard. By the end of the week he was simply a walking fever. Hour by hour he grew more bitter. What the Christian Scientists call malicious animal magnetism seemed to radiate from him like heat from a stove. From my place in the courtroom, standing upon a table, I looked directly down upon him, sweating horribly and pumping his palm-leaf fan. His eyes fascinated me; I watched them all day long. They were blazing points of hatred. They glittered like occult and sinister gems. Now and then they wandered to me, and I got my share, for my reports of the trial had come back to Dayton, and he had read them. It was like coming under fire.

Thus he fought his last fight, thirsting savagely for blood. All sense departed from him. He bit right and left, like a dog with rabies. He descended to demagogy so dreadful that his very associates at the trial table blushed. His one yearning was to keep his yokels hated up – to lead his forlorn mob of imbeciles against the foe. That foe, alas, refused to be alarmed. It insisted upon seeing the whole battle as a comedy. Even [Clarence] Darrow, who knew better, occasionally yielded to the prevailing spirit. One day he lured poor Bryan into the folly I have mentioned: his astounding argument against the notion that man is a mammal. I am glad I heard it, for otherwise I’d never believe it. There stood the man who had been thrice a candidate for the Presidency of the Republic – there he stood in the glare of the world, uttering stuff that a boy of eight would laugh at. The artful Darrow led him on: he repeated it, ranted for it, bellowed it in his cracked voice. So he was prepared for the final slaughter. He came into life a hero, a Galahad, in bright and shining armor. He was passing out a poor mountebank.

Lovely term, that: mountebank.

Multi-trick cyclist

Quentin is game for anything challenging or dangerous. Bungee-jumping, for example. And now this. At £695 it’s not cheap. There’s a two-wheel version with seat for £699.95 which would be more my style. About the same price as an Apple Watch Series 2! Unlike the watch, though, it’s illegal on UK pavements and roads.

Quentin’s other electric vehicle is indeed a BMW.

Green tech irony

Aw, isn’t that nice. The Kentucky Coal Mining Museum is switching to solar power to save money.

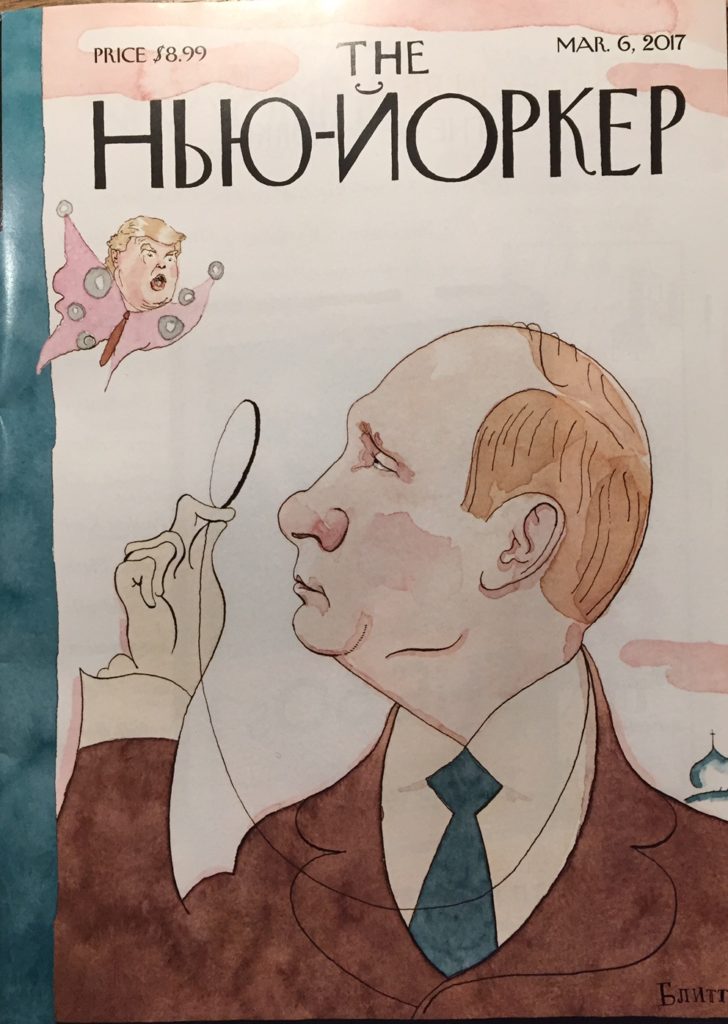

At last, some action from the EU

Good news from the Electronic Freedom Foundation:

European Union Announces Plan for Privacy Wall Around U.S.

European Union Commissioner for Justice Vera Jourova announced plans today to permanently protect Europeans’ data from U.S. government spying with the newest transnational data agreement: Privacy Wall. Once approved by the European Commission, the EU will begin constructing a thirty-foot wall around the United States. Only U.S. tech companies that comply with EU privacy restrictions and prohibit U.S. government access to their data will be given fiber optic grappling hooks to transport Europeans’ data across the Atlantic, over the wall, and back to their U.S.-based servers. U.S. lawmakers appeared unfazed by U.S. companies’ complaints that Privacy Wall will effectively kill their business abroad, but they responded to alarm bells raised by officials in the intelligence community who are concerned about losing generalized access to Europeans’ data.

Hmmm… Pity it’s April 1st.

Jimmy Breslin, RIP

Jimmy Breslin died last week at the age of 88. May he rest in peace: his writing gave some of us a lot of pleasure. The NYT gave him his due in a nice obit. Sample:

Love or loathe him, none could deny Mr. Breslin’s enduring impact on the craft of narrative nonfiction. He often explained that he merely applied a sportswriter’s visual sensibility to the news columns. Avoid the scrum of journalists gathered around the winner, he would advise, and go directly to the loser’s locker. This is how you find your gravedigger.

“So you go to a big thing like this presidential assassination,” he said in an extended interview with The New York Times in 2006. “Well, you’re looking for the dressing room, that’s all. And I did. I went there automatic.”

And if you’re wondering what that refers to, here’s his column on the funeral of JFK.

The next war

Interesting snippet from Tom Ricks:

I interviewed Eric Schmidt of Google fame, who has been leading a civilian panel of technologists looking at how the Pentagon can better innovate. He said something I hadn’t heard before, which is that artificial intelligence helps the defense better than the offense. This is because AI always learns, and so constantly monitors patterns of incoming threats. This made me think that the next big war will be more like World War I (when the defense dominated) than World War II (when the offense did).

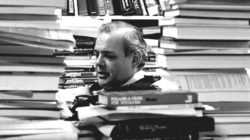

Bob Silvers: getting it right

“In one of my first articles, I used the phrase ‘in terms of.’ He insisted on deleting it, because, he explained, writers used it as filler when they thought there was some relation between A and B but did not know what the relation was.”

Robert Darnton, remembering Bob Silvers, founder of The New York Review of Books, who has died after a short illness.

The ultimate tip for writers (and graduate students)

First drafts don’t have to be perfect. They just have to be written!