Category Archives: Asides

Frozen Buddha

The Cedar in winter

Smugmugs

Grotesque* garden ‘ornaments’. Taken using the intriguing Pro HDR App on the iPhone.

* Which reminds me of what Sydney Smith famously said upon coming on Mrs Grote wearing a turban. “Now I know the meaning of grotesque”.

Down Arrow

Winter menu

We went Christmas shopping this afternoon and wondered why the town seemed strangely deserted. It was, for example, easy to park, which is unheard-of at this time of year. And then, emerging from a bookshop, we realised why. The long-forecast snow had finally arrived. All at once the streets were eerily quiet, and one was reminded of how snow absorbs sound. It was strange to see how bars and restaurants, with their fires (real or fake), customers and bustling staff, suddenly seemed more inviting. I paused outside one and photographed its billboard, now half-obscured by snow. But we didn’t go in: we had meals to prepare, promises to keep.

Walking back to the car, I found myself thinking of the opening sequences of John Huston’s film of Joyce’s short story, The Dead, with the carriages delivering the guests to the Morkan sisters’ annual party, each one arriving with a light dusting of snow on their coats. And then I remembered the wonderful closing passage of the story, as Gabriel Conroy broods in his hotel bedroom on what his (now-sleeping) wife has told him about the young boy who had loved her as a girl.

A few light taps upon the pane made him turn to the window. It had begun to snow again. He watched sleepily the flakes, silver and dark, falling obliquely against the lamplight. The time had come for him to set out on his journey westward. Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

I’ve just looked out. The snow has stopped falling. But the landscape has been transformed. A muddy garden has suddenly become pristine, marred only by the tracks of the cats’ paws. Trees which had been denuded of leaves have become exquisite ice-sculptures. And it’s so, so quiet. As Yeats might have said: I shall have some peace here tonight, for peace comes dropping slow.

Stenographers to power: time to squeak up or be squashed

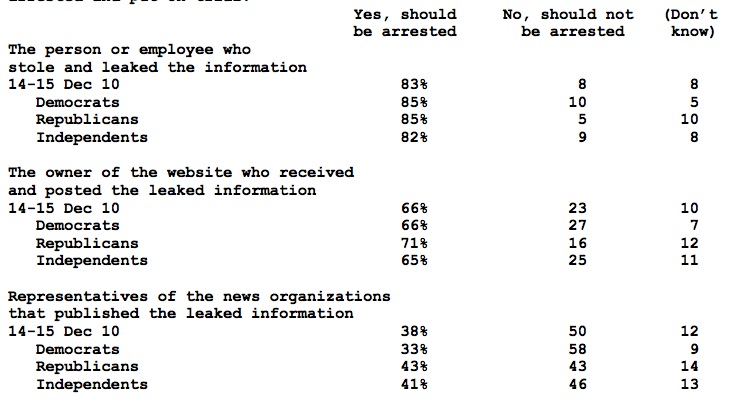

Excerpt from the most recent Fox News poll about WikiLeaks. Note the similarity between Republicans and Democrats. And the more lenient view respondents appear to take towards the New York Times, which, after all, is also publishing the leaked cables.

After writing the previous post, I came on Jay Rosen’s excellent piece about the failure of US mainstream journalism in the run-up to the Iraq war, and that in turn led to Michael Massing’s magisterial piece in the NYRB in 2004. Massing opens his critique thus:

In recent months, US news organizations have rushed to expose the Bush administration’s pre-war failings on Iraq. “Iraq’s Arsenal Was Only on Paper,” declared a recent headline in The Washington Post. “Pressure Rises for Probe of Prewar-Intelligence,” said The Wall Street Journal. “So, What Went Wrong?” asked Time. In The New Yorker, Seymour Hersh described how the Pentagon set up its own intelligence unit, the Office of Special Plans, to sift for data to support the administration’s claims about Iraq. And on “Truth, War and Consequences,” a Frontline documentary that aired last October, a procession of intelligence analysts testified to the administration’s use of what one of them called “faith-based intelligence.”

Watching and reading all this, one is tempted to ask, where were you all before the war? Why didn’t we learn more about these deceptions and concealments in the months when the administration was pressing its case for regime change—when, in short, it might have made a difference? Some maintain that the many analysts who’ve spoken out since the end of the war were mute before it. But that’s not true. Beginning in the summer of 2002, the “intelligence community” was rent by bitter disputes over how Bush officials were using the data on Iraq. Many journalists knew about this, yet few chose to write about it.

“That’s not getting the story wrong”, writes Rosen. “That’s redefining the job as: reflecting what the government thinks.”

This was the nadir. This was when the watchdog press fell completely apart: On that Sunday when Bush Administration officials peddling bad information anonymously put the imprimatur of the New York Times on a story that allowed other Bush Administration officials to dissemble about the tubes and manipulate fears of a nuclear nightmare on television, even as they knew they were going to war anyway.

The government had closed circle on the press, laundering its own manipulated intelligence through the by-lines of two experienced reporters, smuggling the deed past layers of editors, and then marching it like a trained dog onto the Sunday talk shows to perform in a lurid doomsday act.

Something similar is going on now with WikiLeaks. The American public is being softened up for another Administration ‘coup’. The Fox News poll suggests that this time it’ll be even easier to pull it off.

How WikiLeaks is morphing into WMD 2.0

Glenn Greenwald is right. We’re watching a re-run of the stenographers to power in the mainstream media picking up the signals from the political establishment (especially in the US) and obligingly parroting the party line. “The government and establishment media”, writes Greenwald,

are jointly manufacturing and disseminating an endless stream of fear-mongering falsehoods designed to depict them as scary villains threatening the security of The American People and who must therefore be stopped at any cost.

An example: the way most media outlets (even the august New York Times) have relayed the lie that WikiLeaks has “dumped” 250,000 cables into the public domain. This seems to be entirely untrue: only a tiny fraction of the trove has actually been published — and not by WikiLeaks but by the five serious newspapers that have been given access to the material. Whether by accident or design, though, the effect of endlessly repeating the 250,000 falsehood is to demonise WikiLeaks and its founder, Julian Assange. It’s all eerily reminiscent of the way in which the American public were misled in the run-up to the Iraq war — with nameless fears of terrible threats (WMDs) plus demonisation of an individual leader (then it was Saddam, now it’s Assange and Bradley Manning, the soldier accused of collecting the cables and giving them to WikiLeaks).

It’s no surprise that the US official reaction to WikiLeaks seems hysterical: it is. And contradictory: witness Greenwald’s dissection of Vice President Biden’s oscillations on the extent of the “damage” caused by the leaked cables. One minute (December 16) he’s on record saying:

I don’t think there’s any damage. I don’t think there’s any substantive damage, no. Look, some of the cables are embarrassing . . . but nothing that I’m aware of that goes to the essence of the relationship that would allow another nation to say: “they lied to me, we don’t trust them, they really are not dealing fairly with us.”

Now he’s been taped for the edition of Meet the Press going out tomorrow saying:

This guy has done things that have damaged and put in jeopardy the lives and occupations of other parts of the world. He’s made it more difficult for us to conduct our business with our allies and our friends. For example, in my meetings — you know I meet with most of these world leaders — there is a desire to meet with me alone, rather than have staff in the room: it makes things more cumbersome — so it has done damage.

Could it be, Greenwald wonders, that someone in the Attorney-General’s office quietly warned Biden that his declaration about no “substantive damage” might undermine attempts to convict Assange on espionage grounds?

But what’s really troubling is the way in which mainstream media seem to playing along with all this. Worse still, nobody seems to be paying much attention to the way that Bradley Manning is being incarcerated. The Daily Beast has an interesting report of the conditions under which he is being confined:

The conditions under which Bradley Manning is being held would traumatize anyone. He lives alone in a small cell, denied human contact. He is forced to wear shackles when outside of his cell, and when he meets with the few people allowed to visit him, they sit with a glass partition between them. The only person other than prison officials and a psychologist who has spoken to Manning face to face is his attorney, who says the extended isolation—now more than seven months of solitary confinement—is weighing on his client’s psyche.

When he was first arrested, Manning was put on suicide watch, but his status was quickly changed to “Prevention of Injury” watch (POI), and under this lesser pretense he has been forced into his life of mind-numbing tedium. His treatment is harsh, punitive and taking its toll, says Coombs.

To any detached observer, this regime constitutes a form of torture — as, in fact, the UK implicitly recognised when it eventually stopped using it on IRA prisoners in Northern Ireland. Last week the New Yorker carried a really thoughtful article about solitary confinement by Atul Gawande in which he said this:

This past year, both the Republican and the Democratic Presidential candidates came out firmly for banning torture and closing the facility in Guantánamo Bay, where hundreds of prisoners have been held in years-long isolation. Neither Barack Obama nor John McCain, however, addressed the question of whether prolonged solitary confinement is torture. For a Presidential candidate, no less than for the prison commissioner, this would have been political suicide. The simple truth is that public sentiment in America is the reason that solitary confinement has exploded in this country, even as other Western nations have taken steps to reduce it. This is the dark side of American exceptionalism. With little concern or demurral, we have consigned tens of thousands of our own citizens to conditions that horrified our highest court a century ago. Our willingness to discard these standards for American prisoners made it easy to discard the Geneva Conventions prohibiting similar treatment of foreign prisoners of war, to the detriment of America’s moral stature in the world. In much the same way that a previous generation of Americans countenanced legalized segregation, ours has countenanced legalized torture. And there is no clearer manifestation of this than our routine use of solitary confinement—on our own people, in our own communities, in a supermax prison, for example, that is a thirty-minute drive from my door. [Emphasis added.]

What’s strange and disturbing to an observer on this side of the Atlantic is watching the Obama, administration heading down the same moral cul-de-sac as that traversed by his predecessor.

Filtering the Firehose: the usefulness of Twitter

Over the years I’ve been using the following rule as a kind of litmus test: if the mainstream media is baffled by a technological innovation then the odds are that it’s a significant development. So it was originally with the Web (“the Citizen Band radio de nos jours” was how one British newspaper editor described it to me in the early 1990s), SMS, blogging and social networking. And, of course Twitter. I’ve lost count of the number of sensible people who made a point of declaring themselves “baffled” by Twitter. So now it’s amusing to see them creeping, tentatively, one by one, onto the service, and setting themselves up to follow me plus a few genuine Twittercelebs — Alan Rusbridger, for example, or Stephen Fry. All of which explains, I guess, why Twitter has put on 100 million new users in 2010.

The standard line for the Twitter-sceptics is that they cannot for the life of them see what they would use it for. My standard response is to explain why I find it valuable: it enables me to plug into a thought-stream that I find useful and valuable. This is because I follow only two categories of people: those whom I know personally; or those whose thoughts I find stimulating, informative or wise. I also point out to sceptics that when one has a reasonable Twitter following, it can be a good way of getting intelligent answers to questions like “How do I [statement of technical problem]?” or “Has anyone had this problem with [software package]?” or “Does anyone know of a reference for [quote]?” Generally, though, my interrogators do not seem to find these explanations helpful and they go away shaking their heads in wonderment at the peculiarities of geeks.

For me, the WikiLeaks controversy has highlighted the usefulness of Twitter. It made me realise that essentially it has become a human-mediated RSS feed. The people I follow on the service are essentially filtering the firehose for me. And hopefully I am doing the same for them.

As usual, Dave Winer — one of the wisest filters in my stream — has interesting things to say about this.

Twitter is useful, imho, for two things:

1. As a way to share links.

2. As a way to speak your mind.

These days I use it almost exclusively for #1. Very little of #2.

People just aren’t that interested in what other people think. And it’s damned difficult to speak your mind 140 characters at a time. Most of the time you can anticipate in advance what the misunderstandings will be, and self-edit. Then self-censor. Why bother going through all that michegas.

But as a link-sharing tool, it is really excellent.

(I respectfully disagree with his claim about people not being “that interested”. I am generally very interested in what he thinks.) But, being Dave, he has gone the extra mile with this idea. First of all, he publishes a link archive which has all the links he has published since 2009. He’s also been flowing his links into a special WordPress blog.

“Maybe”, he muses,

I’m mostly using Twitter the way people use del.icio.us.

Maybe there’s a lesson in there. Perhaps if we figure out how to decentralize del.icio.us, we’ll be on the way to decentralizing Twitter? Maybe all del.icio.us needed was to become realtime, and it would have become Twitter?

BTW, I often have the same idea about Flickr. It’s a gem, with a huge and influential user base, to this day. With a little love and care it might blossom into something really wonderful.

Yep. But it’s already pretty good.

LATER: There are rumours that Yahoo is planning to shut down del.icio.us. Hmmm… another reason to be suspicious of cloud computing. Dave Briggs has just published a good post about this.