My Observer colleague Peter Preston had terrific piece about the lawyers-vs-Twitter controversy in yesterday’s paper in which he highlighted an aspect of all this that has not received the attention it deserves. This is the fact that the motive force behind the growth in privacy injunctions is not just the intrusiveness of the British tabloid media, but the enterprising greed of London’s leading law firms. As he puts it,

The other defining change of the last 12 years has gradually seen the essential big earner for England’s small but richly endowed libel bar sliding away. English libel law, offering heavy damages, huge fees and real advantages to a prospective litigant, has slowly become another victim of the digital revolution. Our courts have traditionally welcomed cases from all over the globe, however vestigial publication to a UK audience may have been. In that sense, the internet seemed to offer still plumper pickings. But American administrations, first at a state then a national level, became disgusted by the justice they saw meted out to their citizens by the Strand. They have decided that no English ruling that infringes the right to free speech can be enforced across the Atlantic. Our own politicians, spurred into action, are seeking to reform the gross imbalances of English libel.

And this decline in libel rewards is fundamentally connected to the rise in privacy speculation since 1998. Max Mosley could have chosen libel, but opted for privacy. Lawyers, naturally, have moved into this fresh, potentially lush area of litigation. Sweeping injunctions – nobody has quite counted them yet – have become the weapon of first resort. Sometimes (as with Trafigura’s attempt to gag the Guardian) the case has been too outrageous to endure. More typically, though, the queue of celebrities at the court door has succeeded in buying expensive secrecy for marital misdeeds – even if some, such as Andrew Marr, eventually repented of going to court.

(Emphasis added).

What’s going on, I suspect, is that law firms are encouraging clients to splash out on what they (the lawyers, that is) must know is futile expenditure. In the case of footballers earning anything up to £200k a week, the fees probably look like small beer, so there’s clearly room for business expansion here — for lawyers.

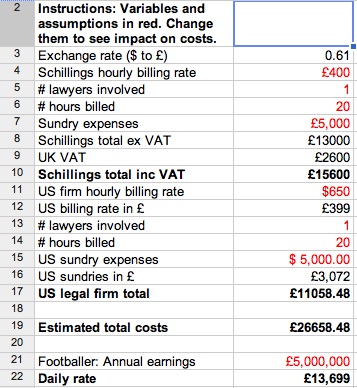

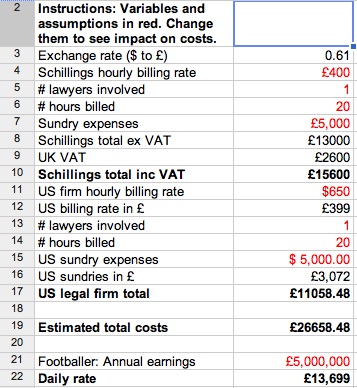

In the interests of helping innocent footballers I’ve built a simple DIY calculator which will enable the average footballer to work out how much it will cost him to fail to get a US court to force Twitter to reveal the identify of Twitterers. It assumes that a US law firm will also be needed to do the business on the American side. On the assumptions I started with, it looks like the minimum cost would be about two days’ wages.