Perceptive Tech review column by Wade Roush.

For book publishers, color screens are interesting but probably not revolutionary. Vook titles like The Breakaway Japanese Kitchen ($4.99), a cookbook that bundles recipes with related instructional videos, provide a taste of what's possible. But with most long-form writing, the words are paramount. If their purpose is to stimulate the mind’s eye, then color and animation are overkill, which is why I doubt that the iPad will wholly undercut the market for the Kindle-style devices.

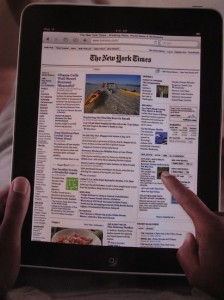

For magazine, newspaper, and textbook publishers, on the other hand, the iPad and the wave of tablet devices just behind it create enormous opportunities. Magazines are distinguished from books not merely by their periodical nature and their bite-size articles but by their design. If digital-age readers still want information that’s organized and ornamented in the fashion of good magazines–and there’s no reason to think they don’t–then devices that mimic the form and ergonomics of old-fashioned print pages will be needed to deliver it.

But to succeed on the new platforms, publishers will have to innovate, not simply imitate established media: they will have to move beyond the current crop of static digital magazines. The problem with most of the publications built on e-magazine platforms from Zinio, Zmags, and other startups is that they are simply digital replicas of their print counterparts, perhaps with a few hyperlinks thrown in as afterthoughts. Publishers should look for better ways to use tablet screens such as the iPad’s, with its multitouch zooming and scrolling capabilities, and to make their content interactive.

And an interesting (and much longer) New Yorker piece by Ken Auletta, which suggests that the real significance of the eBook boom will be a radical rethinking of the publishing business.

Tim O’Reilly, the founder and C.E.O. of O’Reilly Media, which publishes about two hundred e-books per year, thinks that the old publishers’ model is fundamentally flawed. “They think their customer is the bookstore,” he says. “Publishers never built the infrastructure to respond to customers.” Without bookstores, it would take years for publishers to learn how to sell books directly to consumers. They do no market research, have little data on their customers, and have no experience in direct retailing. With the possible exception of Harlequin Romance and Penguin paperbacks, readers have no particular association with any given publisher; in books, the author is the brand name. To attract consumers, publishers would have to build a single, collaborative Web site to sell e-books, an idea that Jason Epstein, the former editorial director of Random House, pushed for years without success. But, even setting aside the difficulties of learning how to run a retail business, such a site would face problems of protocol worthy of the U.N. Security Council—if Amazon didn’t accuse publishers of price-fixing first.

It’s the old story: digital technology means having to rethink more or less everything:

Jason Epstein believes that publishers have been handed a golden opportunity. The agency model, he says, is really another form of the consortium he proposed a decade ago: “Publishers will be selling digital books directly to the iPad. They are using the iPad as a kind of universal warehouse.” By doing so, they create opportunities to cut payroll and overhead costs. Epstein said that e-books could also restore editorial autonomy. “When I went to work for Random House, ten editors ran it,” he said. “We had a sales manager and sales reps. We had a bookkeeper and a publicist and a president. It was hugely successful. We didn’t need eighteen layers of executives. Digitization makes that possible again, and inevitable.”

Auletta closes his piece with speculation that Amazon (and maybe, one day, Apple) will move to exclude publishers from the process and deal directly with authors. After all, most readers don’t buy books because they’re published by a particular publishing house. For them, the author is the brand.

Interesting stuff.