Category Archives: Amazon

Facebook: (yet) another scandalous revelation

If you’re a cynic about corporate power and (lack of) responsibility — as I am — then Facebook is the gift that keeps on giving. Consider this from the NYT this morning:

For years, Facebook gave some of the world’s largest technology companies more intrusive access to users’ personal data than it has disclosed, effectively exempting those business partners from its usual privacy rules, according to internal records and interviews.

The special arrangements are detailed in hundreds of pages of Facebook documents obtained by The New York Times. The records, generated in 2017 by the company’s internal system for tracking partnerships, provide the most complete picture yet of the social network’s data-sharing practices. They also underscore how personal data has become the most prized commodity of the digital age, traded on a vast scale by some of the most powerful companies in Silicon Valley and beyond.

The deals described in the documents benefited more than 150 companies — most of them tech businesses, including online retailers and entertainment sites, but also automakers and media organizations, and include Amazon, Microsoft and Yahoo. Their applications, according to the documents, sought the data of hundreds of millions of people a month, the records show. The deals, the oldest of which date to 2010, were all active in 2017. Some were still in effect this year.

Is there such a condition as scandal fatigue? If there is, then I’m beginning to suffer from it.

Tim Wu’s top ten antitrust targets

He writes:

If antitrust is due for a revival, just what should the antitrust law be doing? What are its most obvious targets? Compiled here (in alphabetical order) , and based on discussions with other antitrust experts, is a collection of the law’s most wanted — the firms or industries that are ripe for investigation.

Amazon

Investigation questions: Does Amazon have buying power in the employee markets in some areas of the country? Does it have market power? Is it improperly favoring its own products over marketplace competitors?

AT&T/WarnerMedia

Investigation question: In light of this, was the trial court’s approval of the AT&T and Time Warner merger clearly in error?

Big Agriculture

Over the last five years, the agricultural seed, fertilizer, and chemical industry has consolidated into four global giants: BASF, Bayer, DowDuPont, and ChemChina. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, seed prices have tripled since the 1990s, and since the mergers, fertilizer prices are up as well.

Investigation question: Were these mergers wrongly approved in the United States and Europe?

Big Pharma

The pharmaceutical industry has a long track record of anticompetitive and extortionary practices, including the abuse of patent rights for anticompetitive purposes and various forms of price gouging.

Investigation and legislative questions: Are there abuses of the patent system that are still ripe for investigation? Can something be done about pharmaceutical price gouging on drugs that are out of patent or, perhaps more broadly, the extortionate increases in the prices of prescription drugs?

Facebook

Having acquired competitors Instagram and WhatsApp in the 2010s in mergers that were arguably illegal, it has repeatedly increased its advertising load, incurred repeat violations of privacy laws, and failed to secure its networks against foreign manipulation while also dealing suspicious blows to competitor Snapchat. No obvious inefficiencies attend its dissolution.

Investigation questions: Should the Instagram and WhatsApp mergers be retroactively dissolved (effectively breaking up the company)? Did Facebook use its market power and control of Instagram and Instagram Stories to illegally diminish Snapchat from 2016–2018?

Google

Investigation question: Has Google anticompetitively excluded its rivals?

Ticketmaster/Live Nation

Investigation questions: Has Live Nation used its power as a promoter to protect Ticketmaster’s monopoly on sales? Was Songkick the victim of an illegal exclusion campaign? Should the Ticketmaster/Live Nation union be dissolved?

T-Mobile/Sprint

Investigation question: Would the merger between T-Mobile and Sprint likely yield higher prices and easier coordination among the three remaining firms?

U.S. Airline Industry

The U.S. airline industry is the exemplar of failed merger review.

Investigation and regulatory questions: Should one or more of the major mergers be reconsidered in light of new evidence? Alternatively, given the return to previous levels of concentration, should firmer regulation be imposed, including baggage and change-fee caps, minimum seat sizes, and other measures?

U.S. Hospitals

Legislative question: Should Congress or the states impose higher levels of scrutiny for health care and hospital mergers?

Investigation question: In light of this, was the trial court’s approval of the AT&T and Time Warner merger clearly in error?

Sic transit gloria

The New York Times today reports that Sears, which more than a century ago pioneered the strategy of selling everything to everyone, filed for bankruptcy protection early on Monday. In terms of ambition, its only rival is Amazon, but even Amazon hasn’t yet got round to selling houses in kit form, as Sears did as long ago as 1908. Here’s one from the catalogue: two bedrooms, two reception rooms, a kitchen and a splendid porch — yours for $1248.00. No mention of a bathroom, though.

Amazon’s minimum wage

Interesting commentary by Alex Tabarrok:

Amazon’s widely touted increase in its minimum wage was accompanied by an ending of their monthly bonus plan, which often added 8% to a worker’s salary (16% during holiday season), and its stock share program which recently gave workers shares worth $3,725 at two years of employment. I’m reasonably confident that most workers will still benefit on net, simply because the labor market is tight, but it’s clear that the increase in the minimum wage was not as generous as it first appeared…

Worth reading in full.

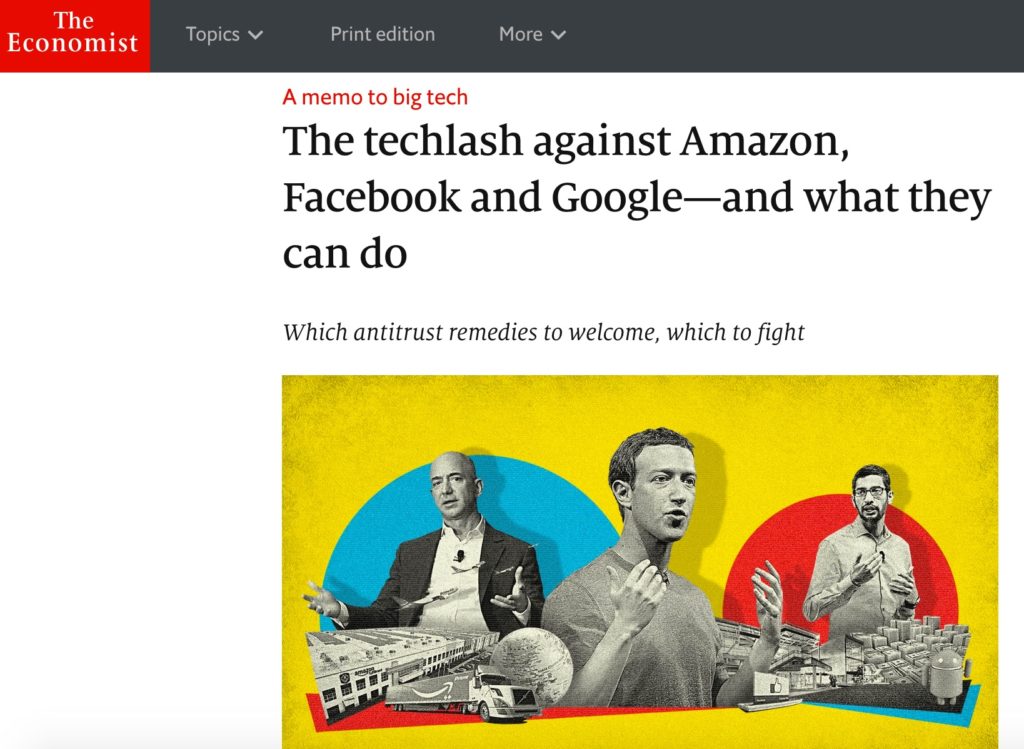

Controlling digital giants: new ideas wanted

This morning’s Observer column:

The five biggest companies in the world are now all digital giants, each wielding monopolistic power in their markets. We are increasingly aware that some of their activities are socially damaging: they are deepening inequality, avoiding taxation, undermining democratic processes, creating addictive products, eroding privacy and so on. And yet, with the odd exception (mostly represented by the European commission), our societies seem transfixed by them, like rabbits paralysed in the tractor’s headlights. Politicians bleat about the need to do something about the digital giants, but so far it’s been all talk and no action.

This is strange because democracies have extensive legal toolkits for dealing with overweening corporate power. We have antitrust and competition laws, monopolies and merger commissions and federal trade commissions coming out of our ears. And yet – again with the single exception of the European commission – they seem unable to deal with the digital giants. Why?

The answer is partly historical and partly ideological…

Amazon’s move into healthcare

This morning’s Observer column about the collaboration between Amazon, Warren Buffett and JP Morgan:

Launching the initiative with his customary folksy bluntness, Buffett said that “the ballooning costs of healthcare act as a hungry tapeworm on the American economy. Our group does not come to this problem with answers. But we also do not accept it as inevitable.” If this – plus the fact that the new venture is to be a not-for-profit enterprise – was intended to be soothing, then it failed. The announcement immediately wiped billions off the valuations of the corporate tapeworms that have for decades fastened like leeches on the US healthcare system. And it’s not Buffett that scares them, but Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s chief executive and founder.

They’re right to to be scared…

The ‘techlash’ goes mainstream

How things change

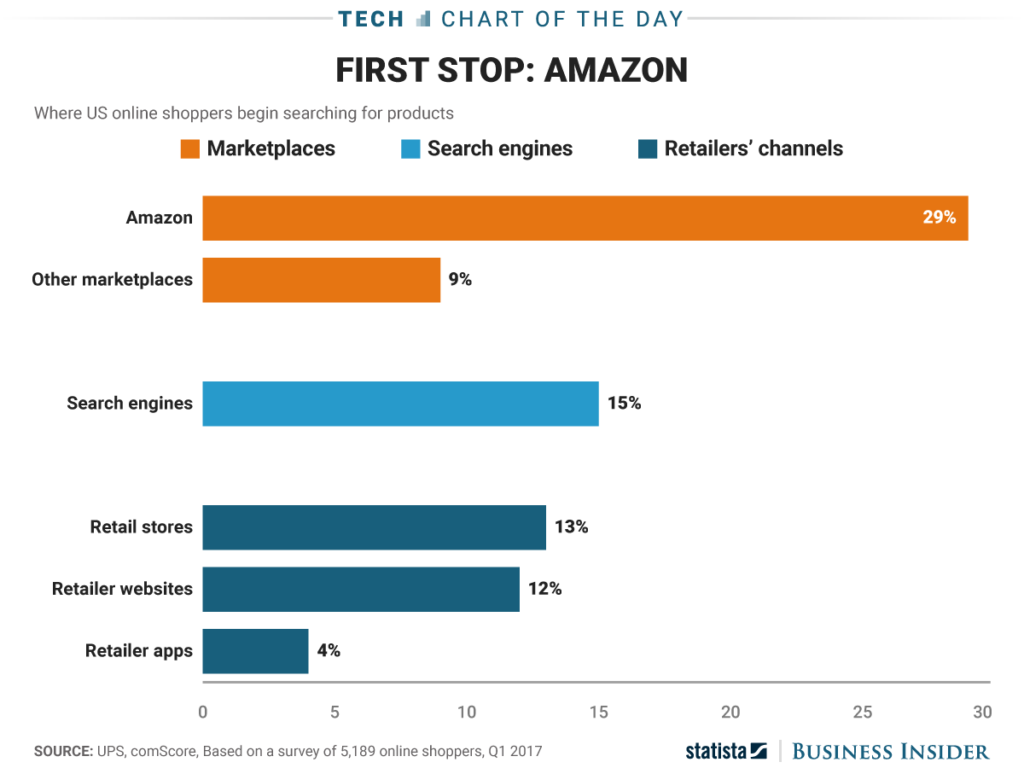

The €2.4B fine on Google handed down by the European Commission stemmed originally from complaints by shopping-comparison sites that changes in Google Shopping that the company introduced in 2008 had amounted to an abuse of its dominance in search. But 2008 was a long time ago in this racket, and shopping-comparison sites have become relatively small beer because Internet users researching possible purchases don’t start with a search engine any more. (Many of them start with Amazon, for example.)

This is deployed (by the Internet giants) as an argument for the futility of trying to regulate behaviour by dominant firms: the legal process of investigation takes so long that the eventual ruling is so out of date as to be meaningless.

This is a convenient argument, but the conclusion isn’t that we shouldn’t regulate these monsters. Nevertheless it is interesting to see how the product search scene has changed over time, as this chart shows.

The obvious solution to the time-lag problem is — as the Financial Times reported on January 3 — for regulators to have “powers to impose so-called “interim measures” that would order companies to stop suspected anti-competitive behaviour before a formal finding of wrongdoing had been reached.” At the moment the European Commission does have powers to impose such measures, but only if it can prove that a company is causing “irrevocable harm” — a pretty high threshold. The solution: lower the threshold.

Amazon and the long game

This morning’s Observer column:

The news that Amazon had acquired Whole Foods Market for $13.7bn sent shivers down the spine of every retailer in America. Shares in Walmart fell 7%, and rival Kroger by 17%. Amazon’s market capitalisation, in contrast, went up by $11bn. So why the fuss? At first sight it seemed straightforward: Amazon wanted to get into food sales, and it fancied having a network of 400 urban stores; and Whole Foods (which some of my American friends call “whole wallet” because of the cost of its products) was ailing. There was also a small political angle: John Mackey, co-founder of Whole Foods, had been enmeshed in a row with an activist investor that threatened to drive him from power; by selling to Amazon, he gets to keep his job. So: small earthquake in food retailing, not many dead?

Er, not quite, and only if you avoid taking the long view. And, with Amazon, the long view is the only one that makes sense…