Two horses and fancy upholstery

My favourite 2CV adaptation turned up at the Boules court the other day. It’s such a lovely piece of work. Note the wicker picnic-box on the rear.

Quote of the Day

”When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

- Charles Goodhart

Often called “Goodhart’s Law” ever since he articulated it in 1975.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

J.S. Bach | Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major, BWV 1042 – III. Allegro

Short but very sweet.

Long Read of the Day

Untangling quantum entanglement

This essay by philosopher Huw Price and physicist Ken Wharton is the most startling thing I’ve read in a while. It’s about one of the strangest aspects of quantum mechanics, the study of the sub-atomic world — in which most of what we have learned in the ‘real’ world of billiard-balls, planets and gravity and Newton’s Laws, doesn’t seem to apply.

And entanglement is at the heart of the weirdness. Wikipedia describes it as

“the phenomenon that occurs when a group of particles are generated, interact, or share spatial proximity in a way such that the quantum state of each particle of the group cannot be described independently of the state of the others, including when the particles are separated by a large distance.”

In their essay, Price and Wharton suggest a new way of thinking about it. Here’s how they open the batting:

Almost a century ago, physics produced a problem child, astonishingly successful yet profoundly puzzling. Now, just in time for its 100th birthday, we think we’ve found a simple diagnosis of its central eccentricity.

This weird wunderkind was ‘quantum mechanics’ (QM), a new theory of how matter and light behave at the submicroscopic level. Through the 1920s, QM’s components were assembled by physicists such as Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger. Alongside Albert Einstein’s relativity theory, it became one of the two great pillars of modern physics.

The pioneers of QM realised that the new world they had discovered was very strange indeed, compared with the classical (pre-quantum) physics they had all learned at school. These days, this strangeness is familiar to physicists, and increasingly useful for technologies such as quantum computing.

The strangeness has a name – it’s called entanglement – but it is still poorly understood. Why does the quantum world behave this strange way? We think we’ve solved a central piece of this puzzle.

Read on and wonder.

Fintan O’Toole on RTE’s slow-rolling crisis.

RTE is Ireland’s national broadcaster and it’s now embroiled in an epic crisis because of revelations about its chaotic management, casual ethics and undercover payments to a leading broadcasting celebrity named Ryan Tubridy. The trigger point for the crisis was the discovery of undercover payments made to Tubridy during the Covid lockdown to compensate him for reductions in his non-broadcasting income caused by the pandemic.

Since public money is involved, the Republic’s legislators opened hearings on the matter, which meant that from Day One my fellow-citizens have been enthralled (and increasingly enraged) by daily revelations about the managerial chaos, ineptitude and arrogance that prevailed in the country’s leading media organisation.

From the outset, though, Tubridy maintained an air of high-minded detachment. All of those non-disclosed payments had been negotiated by his agent, Noel Kelly, disclosed to the revenue authorities, and the tax due on them had been duly paid. “Nothing to see here: any questions see my agent” was the general tenor of his responses.

This pose has exasperated Fintan O’Toole, Ireland’s leading opinion columnist, and he penned a terrific column about it the other day. Like most of his stuff it is hidden behind the Irish Times’s paywall, but since I pay through the nose for a subscription I think it’s time some of his high-octane indignation got a wider airing. So here goes…

He starts with a story about Seamus Heaney, Ireland’s greatest poet since Yeats.

In 1981, Seamus Heaney wrote to his American agent, Selma Warner, about the fees she was demanding for readings by him on US campuses. He was angry because they were too high.

Heaney was not yet quite as famous as he would become, but his reputation was already very considerable and he was a mesmerising performer of his own work. Warner had started to ask for $1,000 for a reading – the equivalent of about $3,300 today.

Heaney’s complaint was that this was too much money: “I do not wish to be a $1,000 speaker. Apart from my moral scruples about whether any speaker or reader is worth anything like that, I do not wish to become a freak among my poet friends, or to press the budgets of departments of literature at a time when the money for education is drying up in the United States.”

Which later brings him to Tubridy:

Let’s not succumb to “my agent made me do it” stories. Agents, however colourful and assertive, are intermediaries: these deals were done between RTÉ and Tubridy.

It was Tubridy’s job to have the “moral scruples”. Kelly is not his Father Confessor – he’s his attack dog. It is always up to the conscience of the client as to whether the dog should be called off before he bites off any particular pound of flesh.

I was the Observer’s TV Critic for nine years, and in that time got to know the British TV industry quite well. I wasn’t much impressed by it. It was fantastically complacent, male-dominated, over-compensated, sexist and unbelievably indulgent to its senior (male) executives. The stories coming out of RTE at the moment bring back memories of those stirring times.

Books, etc.

Revenge of the Librarians

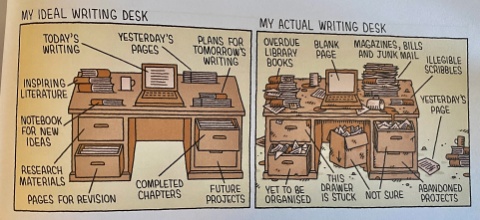

This came as a surprise present from a dear friend the other day. Tom Gauld is a cartoonist and illustrator whose work is regularly published in the The Guardian, The New Yorker and New Scientist. What’s lovely about it is that he has a penetratingly wry insight into the world of writers and would-be writers, e.g.

My commonplace booklet

- Fiat tries to compete with the Vespa Fiat has launched a tiny new EV that supposedly can be driven by 14-year-olds — in Italy at least according to this link. That’s because it has a top speed of only 28mph. It has a small 5.4kWh battery and a range of 47 miles. Neat idea, but somehow I can’t see many teenagers thinking it’d be as cool as a Vespa. Especially if the said scooter were an EV too.

- Meta launches Threads — its supposed alternative to Twitter. On the grounds that columnists should do these things so others don’t have to suffer, I downloaded the app when it first appeared on Thursday morning. Then discovered that in order to access it I needed to open Instagram, which I’ve only used a few times years ago and for which I’d mislaid my password. So went through the usual reset-my-password nonsense and discovered that Instagram is just as nauseating as I remembered, but eventually got through to Threads. It’s kind-of like Twitter, but has the usual Facebook/Meta surveillance practices, and so, after a cursory inspection of naff Threads postings, deleted it. I enjoyed the subliminal wit in Jack Dorsey’s comment on it, though: “All your Threads are belong to us”!

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox ay 6am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!