Window box

Quote of the Day

”A writer is a guy in the hospital wearing one of those gowns that’s open in the back. An editor is walking behind, making sure that nobody can see his ass.”

- John Bennett (who was an editor at the New Yorker)

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Liam O’Flynn & Mark Knopfler | An Droichead (the Bridge)

Long Read of the Day

The End of US Democracy

Bleak conclusion from John Quiggin, an economist not given to hysteria.

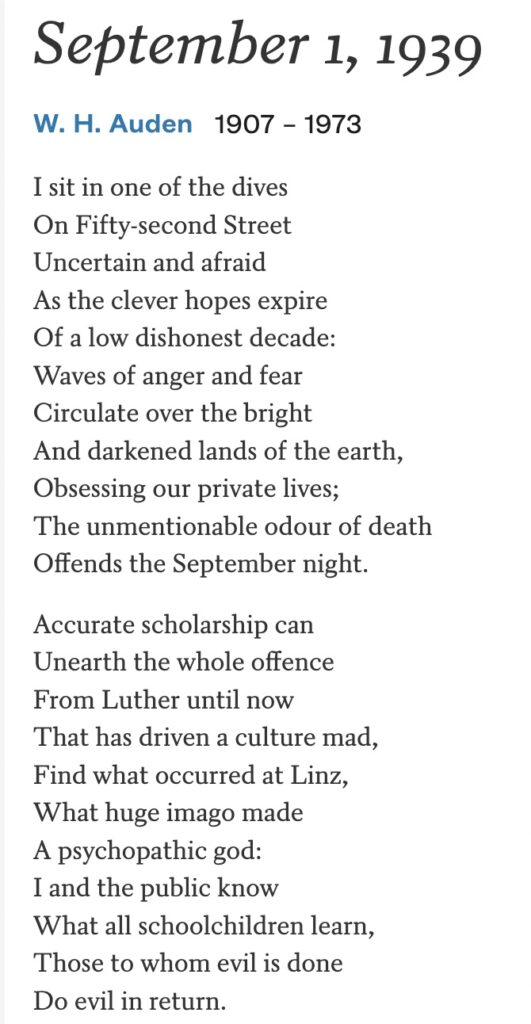

When I wrote back in November 2024 that Trump’s dictatorship was a fait accompli there was still plenty of room for people to disagree. But (with the exception of an announced state of emergency) it’s turned out far worse than I thought possible.

Opposition politicians and judges have been arrested for doing their jobs, and many more have been threatened. The limited resistance of the courts has been halted by the Supreme Court’s decision ending nationwide injunctions. University leaders have been forced to comply or quit. The press has been cowed into submission by the threat of litigation or harm to corporate owners. Political assassinations are laughed about and will soon become routine. With the use of troops to suppress peaceful protests, and the open support of Trump and his followers, more deaths are inevitable, quite possibly on a scale not seen since the Civil War.

The idea that this process might be stopped by a free and fair election in 2026 or 2028 is absurdly optimistic. Unless age catches up with him, Trump will appoint himself as President for life, just as Xi and Putin have done…

Yep. What’s so strange about this moment is that when one expresses a view like Quiggin’s in polite academic circles people tend to look awkward — as if they had suddenly realised that the person to whom they’d been talking was, er, not quite the full shilling. I’m wondering if this is what it was like living in Britain in the 1930s when Winston Churchill was widely regarded as a one-issue fanatic.

Of course it maybe just that people think that what happens in the US is not a problem for us. (Personally, I think they’re wrong about that.) Alternatively, maybe such widespread reluctance to engage with what’s happening signals passive acceptance of the idea that liberal democracy is on the way out and there’s nothing that we can do about it.

Does AI make us dull?

Sunday’s Observer column about an MIT experiment that shows what happens to the brain when writing an essay with the help of AI – and without it.

The project had four research questions: Did participants write significantly different essays when using LLMs, a search engine or only their brains? How did brain activity differ when using LLMs, search or brain-only? How did using LLMs affect memory? And how did LLM usage impact “ownership” of the essays?

What made the experiment distinctive was that all the participants were monitored by electroencephalography (EEG), a non-invasive method used to record electrical activity of the brain. They had to wear special headsets that placed electrodes on their scalps to detect and measure the electrical signals generated by their brains’ neurons as they fired. So it was possible to record the patterns of connections made in participants’ brains as they composed the essays…

My commonplace booklet

Andrew Sullivan on “The consequences of Israel’s hegemony”.

There may be good reasons for backing Israel over Iran’s disgusting regime, or the Saudis’ foul dictators. Everyone is better off without an Iranian nuke. But we should be clear-eyed: This is the Israel we have gone to war for. It is not the Israel of the 20th Century. It is a belligerent, ethno-nationalist country, run in part by ugly racists and those who wish Israel were Arab-free. It may well use this new power for very destructive ends. I hope for an Israeli domestic political miracle that makes this no longer true. But I am not optimistic.

Linkblog

Something I noticed, while drinking from the Internet firehose.

- Watch this robot cook shrimp and clean autonomously Link

Yeah, it kind-of does it. But it wouldn’t cut it in a real kitchen. Also, I don’t like shrimp. And it doesn’t know how to properly wash a greasy pan. But apart from that, it’s interesting.

The link may come up with a paywall block. If it does and you’re using Firefox as your browser, then just clicking to toggle “Reader view” on should give you a readable version of the article. The embedded videos are not on YouTube, alas.

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 5am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!