Closed for business

Quote of the Day

“I find television very educating. Every time somebody turns on the set, I go into the other room and read a book.”

- Groucho Marx

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

František Xaver Pokorný | Concerto in F-major for two horns

New to me, and lovely.

Long Read of the Day

The End of Silicon Politics

Yascha Mounk’s reflections on the lessons to be drawn from the Trump—Musk divorce.

The “HUGEst” political alliance of the century is breaking apart before our eyes in suitably spectacular fashion.

For the last months, the most powerful man in the world, Donald Trump, and the richest man in the world, Elon Musk, were a political item. Musk donated large sums to Trump’s campaign, lavished the newly reelected president with praise on his social network, and neglected his companies to pursue his side quest at the helm of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE). In return, Trump gave Musk unprecedented powers over the federal bureaucracy, staged joint press conferences in the Oval Office, and allowed him to lecture the assembled cabinet before rolling cameras. Nothing better symbolized the supposed “vibe shift” in America than the fact that Trump, practically a social pariah when he was first elected to the White House, could upon his return count on the outspoken support of the world’s most famous entrepreneur—and many other leading figures in Silicon Valley.

But it was also clear from the start that the match between Musk and Trump might prove stormy. The egos of both men are evidently outsized, their temperaments famously volatile. It did not take a genius to predict that their supposedly perfect match might prove short-lived, or even that it would end in acrimony. And yet, the speed with which their epic bromance has turned into an explosive feud is astonishing…

Read on. Mounk thinks the underlying reason for the break-up is the one well-known to divorce lawyers: When marriages fail, “it is often because each partner projected their hopes onto the other, only to discover belatedly that these had all along been misplaced”. Well, well.

Universities must learn to see AI as more than a tool for cheating

Yesterday’s Observer column…

Remember when ChatGPT first broke cover in late 2022 – the excitement, astonishment, puzzlement at what a mere machine could suddenly do? And then the attendant feelings of dread, anger, anxiety and denialism that struck teachers and academic administrations everywhere. This, they fumed, was a tool custom-built to enable cheating on a global scale.

In an academic world – especially the humanities – built on assessing students on the basis of written essays, how would we be able to assign grades when machine-written essays would be undetectable and in some cases much better than what the average student could produce on their own? Since this would be cheating, they concluded, the technology should be banned.

Thus did academia slam the stable door, apparently without troubling itself to reflect upon whether there might be alternative ways of grading student performance. Students, for their part, saw the technology as heaven-sent, and went for it like ostriches that had stumbled upon a hoard of brass doorknobs (as PG Wodehouse would have put it)…

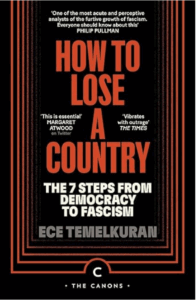

So many books, so little time

My piece in Friday’s edition about reading Otto Dov Kulka’s Landscapes of the Metropolis of Death reminded Andrew Brown of an essay he had written about the book many years ago.

So why did Imre, the conductor of the children’s choir in the family camp at Auschwitz, teach his charges Ode to Joy? What was his purpose? What was his point? Kulka sees the point of having a choir. Without activity, life would have been even closer to unendurable. But why, he asks, did Imre have the children perform a hymn, a manifesto that proclaims human dignity, humanistic values and a faith in the future “in the place where the future was perhaps the only definite thing that did not exist”?

One answer – and clearly the one that all respectable opinion must favour – is that this was a message of hope. Imre (himself gassed on 8 March 1944) knew or hoped that some children might survive, that some might be able to start rebuilding civilisation, and that to do so they needed the noblest things that European civilisation has made: Beethoven, Schiller and Dostoyevsky (another inmate, dying of diphtheria, passed on to Kulka his copy of Crime and Punishment).

This, Kulka says, is one possibility, “a very fine one” in fact. But there is another, apparently far more likely…

Read on. It’s a fine piece.

My commonplace booklet

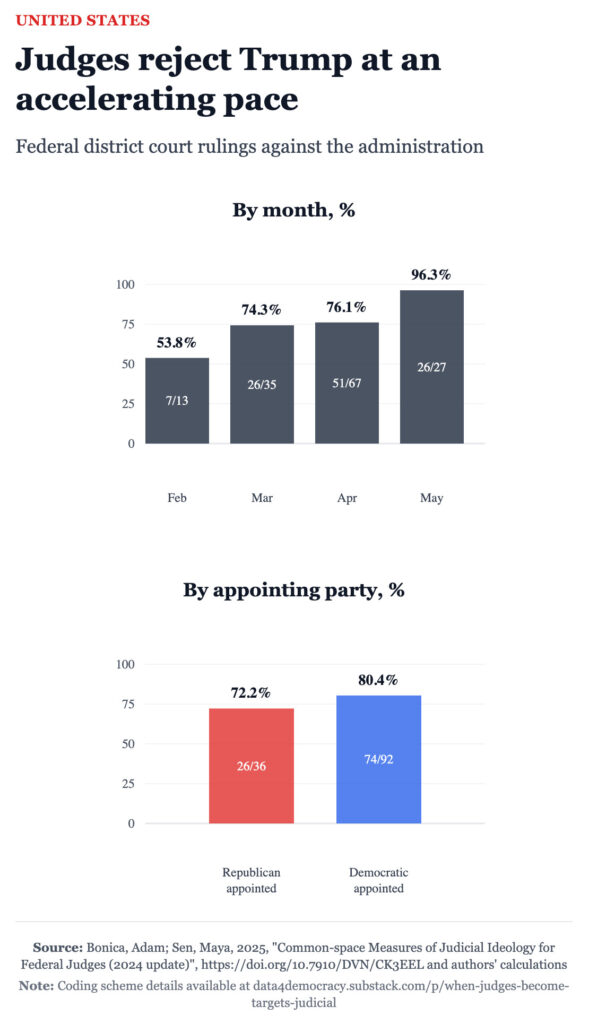

This was the front page of the Financial Times on Saturday. Ponder it for a moment, and reflect on how we got to this nightmarish position, where two insanely-wealthy feuding sociopaths, one a narcissist who has a finger on the nuclear button, the other a ketamine-fuelled man-child who can shut off internet access to the Ukraine military by flicking a switch, are being beseeched by some distressed hedge-fund dudes to “hug and make up”.

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 5am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!