Just One Cornetto

In the 1980s there was a memorable ad for Walls ice cream in which a Venetian gondolier sang “Just One Cornetto” to the tune of O Sole Mio. On my first visit to Venice, on a dark November day in 2008, I was walking on my own down a dark alley when I heard a man singing, and then turned a corner to find a Gondolier (not this one, alas: I didn’t have my camera with me) singing O sole Mio to two entranced American tourists.

Quote of the Day

”I think the ordinary is a very under-exploited aspect of our lives because it’s so familiar.”

- Photographer Martin Parr, RIP

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Luciano Pavarotti | O Sole Mio

Long Read of the Day

11 thoughts on the NSS

James Crabtree’s interesting take on the US National Security Strategy document that is currently roiling European governments.

Samples:

- The drafting process was chaotic. And it shows. From what I understand, an original much longer draft from the White House was junked entirely. Drafting was then handed to Michael Anton, a conservative thinker in the State Dept policy planning department (see below). Anton has since left the administration, but the final, much shorter draft — just 16 pages — was mostly his work. That is where all the civilizational language and harsh European rhetoric comes from.

And

- The NSS is fundamentally economic in focus. “The future belongs to the makers,” as it says. Trump’s first NSS in 2017 centered on Russia and China with a big focus on “great power competition.” This version doesn’t even mention that, and Russia is pleased. Instead, it’s full of stuff about migration, re-industrialization, chips, critical minerals, energy dominance and so on.

The key thing to hold on to, perhaps, is that Trump is incapable of strategy. He just does what he thinks will enrich or popularise him at any particular moment.

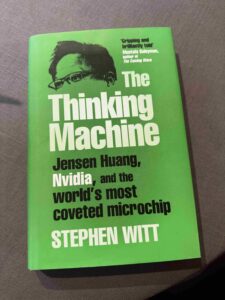

Books, etc.

Just started on this biography of the Levi Strauss de nos jours. Unputdownable so far.

My commonplace booklet

The finance industry in a nutshell

Lending money where it’s needed is what the modern form of finance, for the most part, does not do. What modern finance does, for the most part, is gamble. It speculates on the movements of prices and makes bets on their direction. Here’s a way to think about it: you live in a community that is entirely self-sufficient but produces one cash crop a year, consisting of a hundred crates of mangoes. In advance of the harvest, because it’s helpful for you to get the money now and not later, you sell the future ownership of the mango crop to a broker, for a dollar a crate. The broker immediately sells the rights to the crop to a dealer who’s heard a rumour that thanks to bad weather mangoes are going to be scarce and therefore extra valuable, so he pays $1.10 a crate. A speculator on international commodity markets hears about the rumour and buys the future crop from him for $1.20. A specialist ‘momentum trader’, who picks up trends in markets and bets on their continuation (yes, they do exist), comes in and buys the mangoes for $1.30. A specialist contrarian trader (they exist too) picks up on the trend in prices, concludes that it’s unsustainable and short-sells the mangoes for $1.20. Other market participants pick up on the short-selling and bid the prices back down to $1.10 and then to $1. A further speculator hears that the weather this growing season is now predicted to be very favourable for mangoes, so the crop will be particularly abundant, and further shorts the price to 90 cents, at which point the original broker re-enters the market and buys back the mangoes, which causes their price to return to $1. At which point the mangoes are harvested and shipped off the island and sold on the retail market, where an actual customer buys the mangoes, say for $1.10 a crate.

Notice that the final transaction is the only one in which a real exchange takes place. You grew the mangoes and the customer bought them. Everything else was finance – speculation on the movement of prices. In between the time when they were your mangoes and the time when they became the customer’s mangoes, there were nine transactions. All of them amounted to a zero-sum activity. Some people made money and some lost it, and all of that cancelled out. No value was created in the process.

That’s finance. The total value of all the economic activity in the world is estimated at $105 trillion. That’s the mangoes. The value of the financial derivatives which arise from this activity – that’s the subsequent trading – is $667 trillion. That makes it the biggest business in the world. And in terms of the things it produces, that business is useless. It does nothing and adds no value. It is just one speculator betting against another and for every winner, on every single transaction, there is an exactly equivalent loser.

John Lanchester, London Review of Books

Fabulous writer.

Errata

From Robbie McKendrick:

A small correction, the article and video about the Maggie’s Cancer Support Centre in Dundee are actually STV’s, not Sky’s.

Apologies to Scottish Television.

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 5am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!