Passage to Trinity

All Saints Passage. One of my favourite spots in Cambridge.

Quote of the Day

”The Right Honourable Gentleman is reminiscent of a poker. The only difference is that a poker gives off occasional signs of warmth.”

- Benjamin Disraeli on Prime Minister Robert Peel

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Sharon Shannon & Alan Connor | “Lament For Limerick”

Long Read of the Day

The homevoters and the haut precariat

Perceptive essay by Noah Smith, this time on how societies like the US (and the UK) are stratifying in new ways.

What’s less discussed are the classes of young people who don’t own homes. Some are poor or working-class, and are thus excluded from the economies of urban wealth and asset ownership. Among those are the class now being called the “precariat”, who lack steady employment and are forced to cobble together a living out of a web of tenuous work arrangements and social relationships. Others are successful high-earning PMC types, who might sigh at the price they have to pay for a home in a superstar city, but will eventually pony up the cash and become the next generation of bourgeoisie.

But in between those, I’m sensing there’s another class — people raised middle- or upper-middle class, but who for whatever reason have failed to get on either the income ladder of high-paying yuppie jobs or the wealth ladder of homeownership, and who are thus perpetually in danger of falling down out of the class into which they were born. I want to call these people the haut precariat.

Interesting and original — as ever with Smith. I don’t know how he does it.

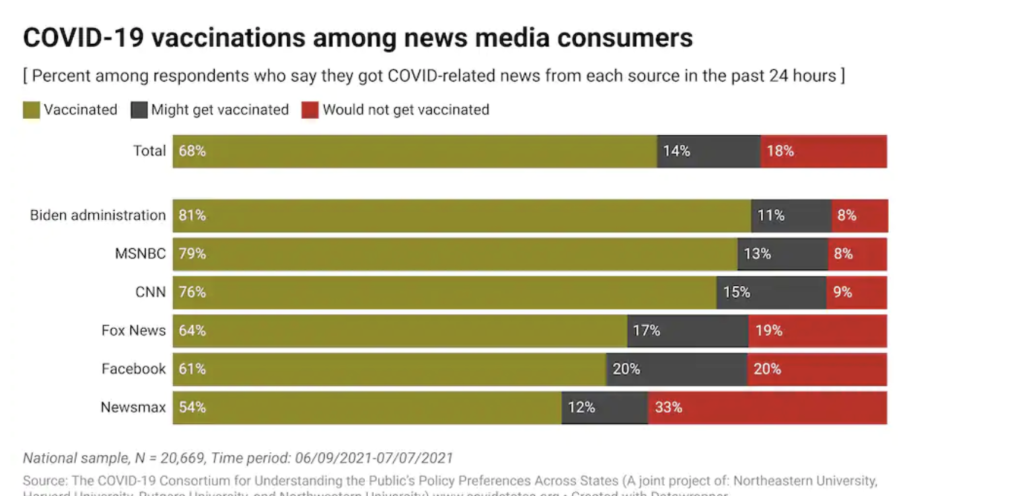

Chart of the Day

From the Washington Post:

Respondents who get news about the coronavirus via Facebook are less likely to get vaccinated than the average American and than non-Facebook users. Sixty-one percent of those Facebook users said they had been vaccinated, vs. 68 percent of the eligible U.S. population and 71 percent of non-Facebook users. The relationship was stronger for those who said that they had received coronavirus news or information only from Facebook and not from any of the other sources mentioned. Sixteen percent of all respondents fall into this category, and only 47 percent of them report being vaccinated, with 25 percent saying they will not get vaccinated.

Cyberwar: a dry run for the real thing

From yesterday’s Financial Times:

Joe Biden has warned that cyber attacks could escalate into a full-blown war as tensions with Russia and China mounted over a series of hacking incidents targeting US government agencies, companies and infrastructure.

Biden said on Tuesday that cyber threats including ransomware attacks “increasingly are able to cause damage and disruption in the real world”.

“If we end up in a war, a real shooting war with a major power, it’s going to be as a consequence of a cyber breach,” the president said in a speech at the Office for the Director of National Intelligence, which oversees 18 US intelligence agencies.

Cold wars can get hot. And, as Biden said later in his speech, Putin has oil and nukes and nothing else.

Humidity is the killer, not heat

Reading about the ‘heat dome’ phenomenon in the Pacific North West, I was puzzled about why high temperatures are deadly in some circumstances but not in others. And then I found this article in Slate.

Why is 120 degrees in Palm Beach not the same as 120 degrees in Palm Springs?

It turns out there’s some truth to the old cliché “it’s not the heat, it’s the humidity.” In scientific terms, it’s called a “wet-bulb temperature,” and understanding it is crucial to surviving—and mitigating—the climate crisis.

In reasonable heat, the human body is very good at maintaining a constant internal temperature of 97 to 99 degrees. When it gets hot outside, our bodies produce sweat; when the sweat evaporates, its transformation from liquid water on your skin to water vapor in the air requires energy. That energy comes from your body’s heat, so as the sweat evaporates, your body cools down.

A dry heat feels comfortable because the evaporation happens so fast that you don’t even notice the sweat on your skin. (This is also why dehydration is a huge risk in desert climates—while you feel the dry air is helping you tolerate the heat, you’re also losing water from your body the whole time. “Hydrate or die” is not just a clever slogan; it’s good science.)

Now suppose you’re in the same amount of heat, but in Palm Beach, where the air is incredibly humid. The air is already holding all the water vapor it can hold. So your sweat stays on your skin, and the heat that the sweat is supposed to remove from your body … stays in your body, and accumulates.

Your body has lost its ability to shed heat, and so your core temperature starts creeping up to approach the temperature of the air around you. Let the process go on long enough, and body temperature rises from comfortable 98 to deadly 108.

The article goes on to say that, according to the best climate models, large areas of the US will experience several weeks of hot wet-bulb temperatures by the middle of this century — i.e. in 30 years’ time. “By 2050, parts of the Midwest and Louisiana could see conditions that make it difficult for the human body to cool itself for nearly one out of every 20 days in the year,” ProPublica reported in September. During these periods of deadly heat, shade and hydration won’t save you. Any human without access to reliable air conditioning risks death.

And of course air conditioning itself contributes to global warming.

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!