Quote of the Day

”Sir Walter Scott, when all is said and done, is an inspired butler.”

- William Hazlitt

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

C.P.E. Bach: Cello Concerto in A | 3 Allegro assai

Sprightly, n’est-ce pas?

Long Read of the Day

Build competence, not literacy

How do you build a culture that emphasises solving problems rather than adhering to processes?

Nice blog post by Rob Miller, useful to anyone building a project team. ‘Literacy’ is about familiarity with processes; competence is about the ability to produce things.

Fusion dreams get a boost? Er, maybe

The NYT reported on an exciting experiment done by the Lawrence Livermore Lab in which 192 huge lasers were pointed at a tiny pellet of hydrogen (“the width of a human hair”) which they then annihilated, producing a burst of more than 10 quadrillion watts of fusion power (which is a non-negligible fraction of the 170 quadrillion watts the sun lavishes on the planet every day). There’s only one snag: the energy burst — “essentially a miniature hydrogen bomb”, says the Times — lasted only 100 trillionth of a second.

To this, Charles Arthur (Whom God Preserve) added his characteristically sardonic comment:

I love the principle of fusion, and I’ve written about it a few times (and stood inside the torus at JET in Oxfordshire – not while it was running), and I’m just as excited – possibly more – as the next person about it, but stories like this are absolute classics of the genre. Incredibly short duration? Check. Incredibly complex array required? Check. Didn’t achieve “ignition” (self-sustaining output)? Check. Excited scientists? Check. It might as well be a story in The Onion; you could, if you wanted, read it as emanating from that august publication, and they wouldn’t have to change a word.

Which is just perfect.

The fiasco in Kabul

An excoriating blast from Professor Paul Cornish, a friend and former colleague, now a distinguished defence and security analyst. Here’s an excerpt:

Instead of confronting this crisis of strategic credibility, too many in strategic leadership positions in the West indulge instead in wishful thinking, displacement activity and even rampant self-justification.

In the UK, with one or two notable exceptions such as James Heappey, the Minister for the Armed Forces, who manages to combine a sense of empathy with honest political realism and a soldier’s instincts for problem solving, we have had the embarrassing spectacle of high-level politicians, public officials and very senior military officers showing just how disconnected they are from this looming strategic reality. Keen to convince the media and the electorate that this is a temporary politico-military malfunction, from which ‘lessons will be learned’ before the normal service of strategic mastery is resumed, we are assured repeatedly that the Taliban surge was unexpected and unpredictable. Really? Ten years ago, following the second of two visits to Afghanistan, I made the following observation at a conference: ‘withdrawal – whenever it happens – should be seen not simply as the desperate ending of the intervention but as the most complex and dangerous part of the intervention. If this is mishandled or rushed, then we might be talking in five years’ time not just of the resurgence of some very unpleasant extremist and criminal groups, but of a regional conflagration.’ My sense of foreboding was premature by five years but if a visiting academic/think tank analyst could see things in this way then plenty of others, in more influential positions, will have come to a similar conclusion. And if the capture of Kabul was indeed so unexpected, why was there not only a ‘Plan A’ for the evacuation but also a ‘Plan B’? Was the capitulation unexpected, or were we preparing for it? As well as presenting a wholly confused, if not disingenuous analysis, the UK’s strategic leadership has also demonstrated an unbeatably inappropriate choice of actions and words: the Foreign Secretary remaining determinedly glued (some have alleged) to a sunbed in Crete while the crisis grew; or the UK Chief of Defence Staff insisting that the Taliban, an implacable enemy of Britain’s armed forces for many years, ‘has changed’ and that British troops are now ‘happy to collaborate’ with them.

The Taliban’s resumption of power in Afghanistan could have a very wide range of local, regional and international consequences, many of them incompatible with Western values and interests: the cancellation of human rights and liberties; the repression and maltreatment of women and girls; discrimination against ethnic and religious minorities; the dismantling of civic society; overreach by Pakistan and India’s reaction to it; the expansion of China’s geostrategic and political interests; and the recrudescence of state-sponsored, anti-Western, Sunni terrorism. In this dismal context, uncomfortable questions must be asked about the West’s reputation as a global strategic actor, about its ‘strategic ambition’ and about the relevance of its vision for the world. Both the US and the UK have presented themselves as expert in the high strategic art of combining ‘hard power’ (i.e., the power of coercion and compulsion) with ‘soft power’ (i.e., the power of attraction and persuasion). Does the Rout of Kabul suggest that either of these is functioning as it should, or is as convincing as is claimed? In the UK, the March 2021 review of national security and defence offered a vision of a post-Brexit ‘Global Britain’, finally achieving its destiny as a ‘force for good in the world’, a ‘soft power superpower’, and a country with globally deployable ‘hard power’. Broadly similar rhetoric was heard at the G7 and NATO summits in June 2021. After Kabul, are any of these promises, offers and assurances convincing? And who would rely upon them? Bells that ring as hollow as this should probably not be rung – at least not in public.

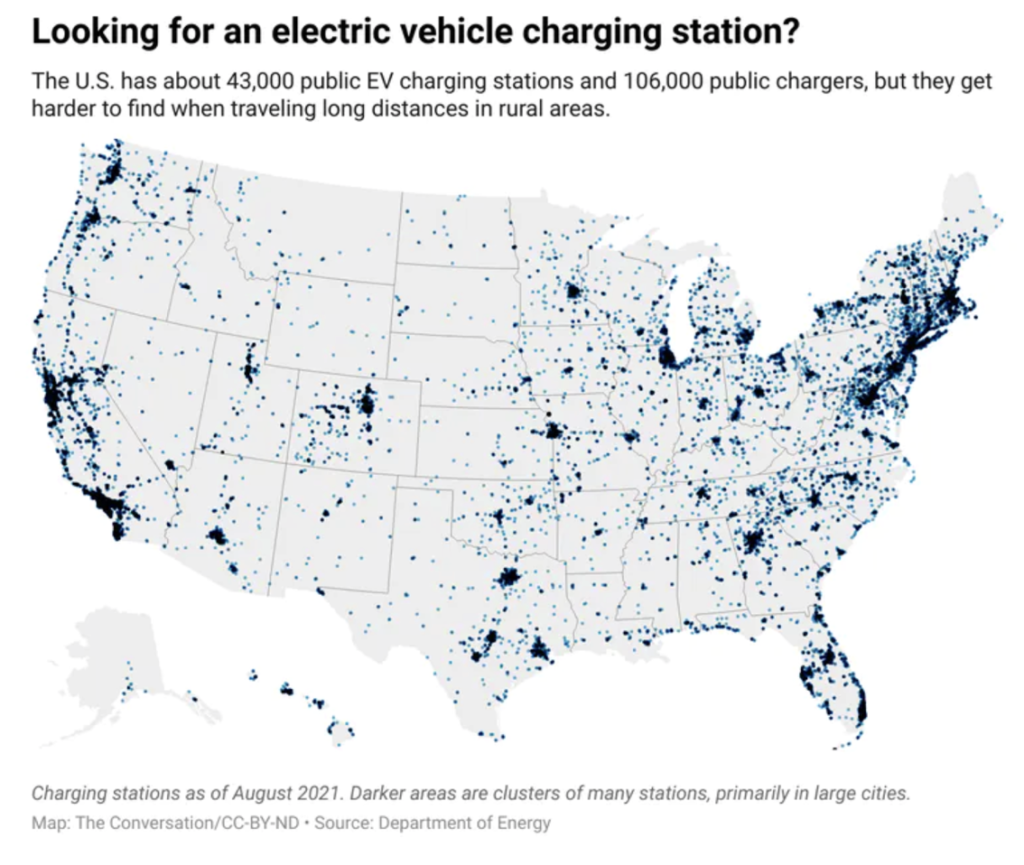

Chart of the Day

Looks like EV owners in lots of places will suffer from range anxiety.

Electrostatic headphones

The piece about electrostatic headphones yesterday prompted a nice email from Thomas Parkhill, who wrote that

Electrostatic headphones have been around since at least the 1970’s, but I think that they have always been a niche even in that rarefied world. Here is the very famous Jecklin Float, which sold for $300 in 1971 – worth looking up.

So I did look them up, and found a delicious review by J. Gordon Holt:

These are some of the most lusciously transparent-sounding headphones we’ve ever put on our ears, but we doubt that they will every enjoy much commercial success, for a couple of reasons.

First, and probably foremost, they are just downright uncomfortable for most people to wear. They feel as awkward as they look. Their width is not adjustable, so they either press uncomfortably against your head or flop loosely all over the place, depending on the fatness of your skull. Also, if you have a short neck, or like to sit hunched down in an easy chair while listening, the bottoms of the ‘phones or their protruding cable get hung on your shoulders.

Sonically, they are extraordinarily good (fig.1), except for two little hitches: They have virtually no deep-bass response; and they have a slightly vowel-like “eeh” coloration that seems to have something to do with the cavity between the headphones and the sides of your head.

The review also quoted the verdict of another audiophile, Bill Sommerwerck, who summed the Jecklin Floats up thus:

They are to hi-fi what a strapless bra is to undergarments.

This blog is also available as a daily newsletter. If you think this might suit you better why not sign up? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-button unsubscribe if you conclude that your inbox is full enough already!