One of the things that people overlook about the Kennedys is how Irish their political machines were. They (and other Irish-American politicos like the Daleys in Chicago) had a mastery of hyperlocal politics that’s quintessentially Irish. Charley Haughey or Bertie Ahern would have recognised Ted Kennedy’s hold on his Massachussetts constituency. In 1968, when the news broke that the Boston consulting firm Bolt Beranek & Newman had been awarded the contract to build the Interface Message Processors (IMPs) which were the ARPANET’s routers, the engineers were surprised to receive a telegram from their local Senator congratulating them on winning the contract to build the “Interfaith Message Processor”.

To anyone raised in rural Ireland, this attention to local detail seems totally familiar. My father — who was a totally non-political person and did not mix with politicians of any stripe — died many years ago in a Cork hospital at 7.15am on a Sunday morning. At 8am, a telegram expressing condolences arrived at our family home. It was from Jack Lynch, who was then the Irish Prime Minister — but also happened to be our local TD (i.e. member of Parliament).

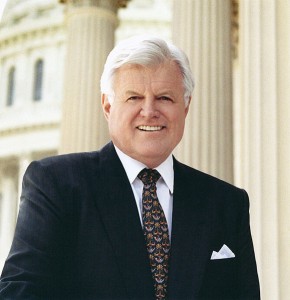

LATER: There’s a good piece in the Guardian by Joyce Carol Oates, who wrote a novel based on the Chappaquiddick incident. Excerpt:

‘There are no second acts in American lives’– this dour pronouncement of F Scott Fitzgerald has been many times refuted, and at no time more appropriately than in reference to the late Senator Ted Kennedy, whose death was announced yesterday. Indeed, it might be argued that Senator Kennedy’s career as one of the most influential of 20th-century Democratic politicians, an iconic figure as powerful, and as morally enigmatic, as President Bill Clinton, whom in many ways Kennedy resembled, was a consequence of his notorious behaviour at Chappaquiddick bridge in July 1969.

Yet, ironically, following this nadir in his life/ career, Ted Kennedy seemed to have genuinely refashioned himself as a serious, idealistic, tirelessly energetic liberal Democrat in the mold of 1960s/1970s American liberalism, arguably the greatest Democratic senator of the 20th century. His tireless advocacy of civil rights, rights for disabled Americans, health care, voting reform, his courageous vote against the Iraq war (when numerous Democrats including Hillary Clinton voted for it) suggest that there are not only “second acts” in American lives, but that the Renaissance concept of the “fortunate fall” may be relevant here: one “falls” as Adam and Eve “fell”; one sins and repents and is forgiven, provided that one remakes one’s life…

STILL LATER: There’s a fine obit in the Economist which concludes:

Yet even when he was carousing—and he sobered up in the 1990s—he was a hell of a senator. He was not a details man; he had a devoted staff for that. But he had passion and energy and a palpable desire to comfort the afflicted. From the moment he entered the Senate, he agitated for civil rights for blacks. His beefy fingerprints are on the Voting Rights Act, the Age Discrimination Act and the Freedom of Information Act. He pushed for an end to the war in Vietnam, for stricter safety rules at work and for sanctions against apartheid South Africa. He sometimes took bold stances while his party dithered: he opposed George Bush junior’s Iraq war from the start. Yet he worked hand-in-glove with Mr Bush to make schools more accountable and to liberalise immigration law, though the latter task defeated them both.

His last quest was to make health insurance universal. He first attempted this in the 1970s. This year he threw all his weight behind Barack Obama’s health plan, before cancer made him too ill to work. Last week, suspecting that the end was near, he urged a change in Massachusetts law to allow a temporary successor to be appointed by the Democratic governor. If this does not happen, the seat could be empty for months, depriving Democrats of their filibuster-proof majority in the Senate—and reminding Americans how big a man, in every sense, they have lost.