PJ O’Rourke RIP

Even when one disagreed with him about politics (which I certainly did), he was great fun and often a joy to read.

The NYT ran a good Obit. Sample:

He was a proud conservative Republican — one of his books was called “Republican Party Reptile: The Confessions, Adventures, Essays and (Other) Outrages of P.J. O’Rourke” — but he was widely admired by readers of many stripes because of his fearless style and his willingness to mock just about anyone who deserved it, including himself. In “Republican Party Reptile” he recalled his youthful flirtation with Mao Zedong.

“But I couldn’t stay a Maoist forever,” he wrote. “I got too fat to wear bell-bottoms. And I realized that communism meant giving my golf clubs to a family in Zaire.”

In 2010, The New York Times invited him and assorted other prominent people to define “Republican” and “Democrat.” He offered this:

“The Democrats are the party that says government will make you smarter, taller, richer and remove the crab grass on your lawn. The Republicans are the party that says government doesn’t work and then get elected and prove it.”

They (the Republicans) don’t make them like that any more.

Quote of the Day

”A spin with P. J. O’Rourke is like a ride in the back of an old pickup over unpaved roads. You get where you’re going fast, with exhilarating views but not without a few bruises.”

- Signe Wilkinson, reviewing PJ’s Parliament of Whores in the New York Times.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Peter Gabriel and Kate Bush | Don’t Give Up

Extraordinary duet. It’s had more than 40m views on YouTube, so they’re doing something right.

An obituary for coal

Every year at this time, subscribers to The Economist (of whom I’m one) get sent a copy of The World Ahead — supposedly looking forward to the coming year.

Given that 2022 is the year when burning coal in a domestic fire will be outlawed, Anne Wroe, the Economist‘s Obituaries editor, contributed “Ashes to Ashes”, an elegant Obituary for the natural resource that made Britain great. I read it aloud to a friend who was busy doing something else at the time and thought that readers who are not Economist subscribers might enjoy it. So here it is:

Everything you need to know about that Andrew Windsor business

Can’t imagine anyone bettering this dispatch in yesterday’s edition of Politico’s London Playbook newsletter.

SHAMING OF PRINCE ANDREW

ROYAL WRONG ‘UN: Queen Elizabeth II will help her son Prince Andrew pay an out-of-court settlement of more than £12 million to a woman who accused him of raping her when she was a child, in exchange for her silence and to prevent him from facing a jury trial. The sordid deal is the final disgrace for the queen’s third child and ends his prospect of ever salvaging his reputation or returning to public life. It raises searching questions about why Britain’s monarch is funding a settlement that saves Andrew from having to defend himself against Virginia Giuffre’s sexual abuse allegations in court. Andrew always claimed he had never met Giuffre and only weeks ago vowed to prove his innocence at a trial. Instead, he got his mum to pay her off. There is also the grim reality that since the queen, Andrew and the royal family derive much, if not all, of their wealth from the British public, it is essentially us who are paying for Andrew to buy his escape from justice. All in all, Tuesday was probably the most humiliating and damaging day for the royals in their recent history.

OUR NOBLE QUEEN: The story splashes most of today’s newspaper front pages. The Telegraph’s Victoria Ward and Josie Ensor report the queen will “partly fund” the settlement, which they are told “exceeds £12 million.” They say the terms of the deal require both Andrew and Giuffre not to discuss the case or the settlement in public. The Times’ Charlotte Wace, Will Pavia, Jonathan Ames and Mario Ledwith hear Andrew settled after pressure from Prince Charles as the case threatened to overshadow this year’s Platinum Jubilee. Playbook is not sure the queen paying off an alleged sexual abuse victim so she can have a party is as good a look as the royals think. The Sun’s Tom Wells say Andrew will never return to the front line of public life. The Mail calls it his “final humiliation.”

Long Read of the Day

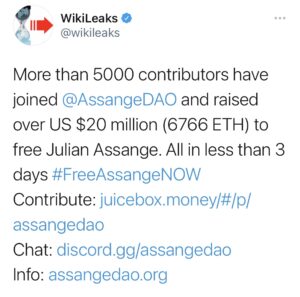

Peter Thiel, the Right’s Would-Be Kingmaker

Long, long piece by Ryan Mac and Lisa Lerer in the New York Times on the current political plans of Silicon Valley’s most disruptive libertarian. There’s no good news in it, except for Republican extremists and maybe Trump supporters. And it provides further confirmation of the extent to which dark money and personal wealth are destroying American democracy.

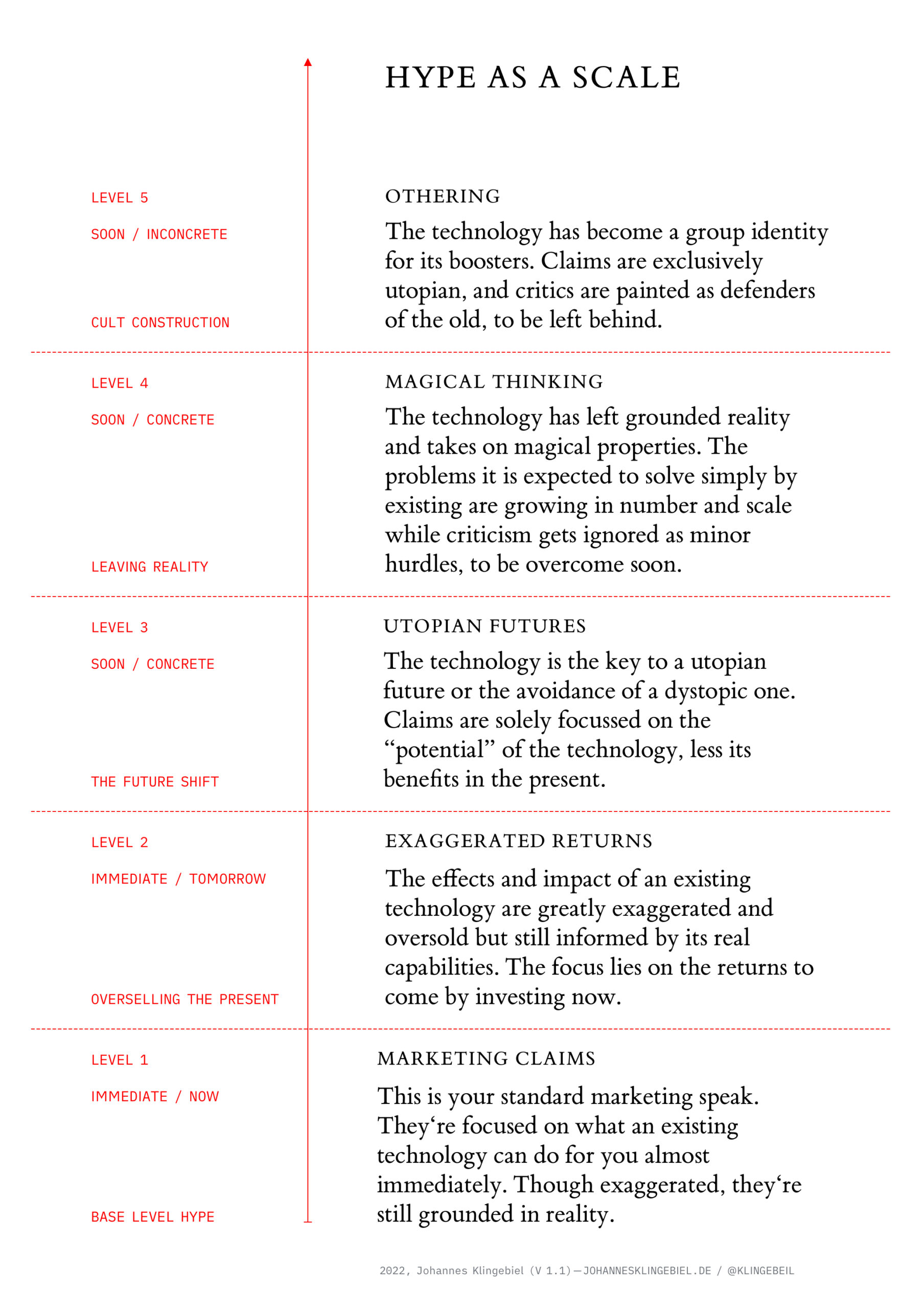

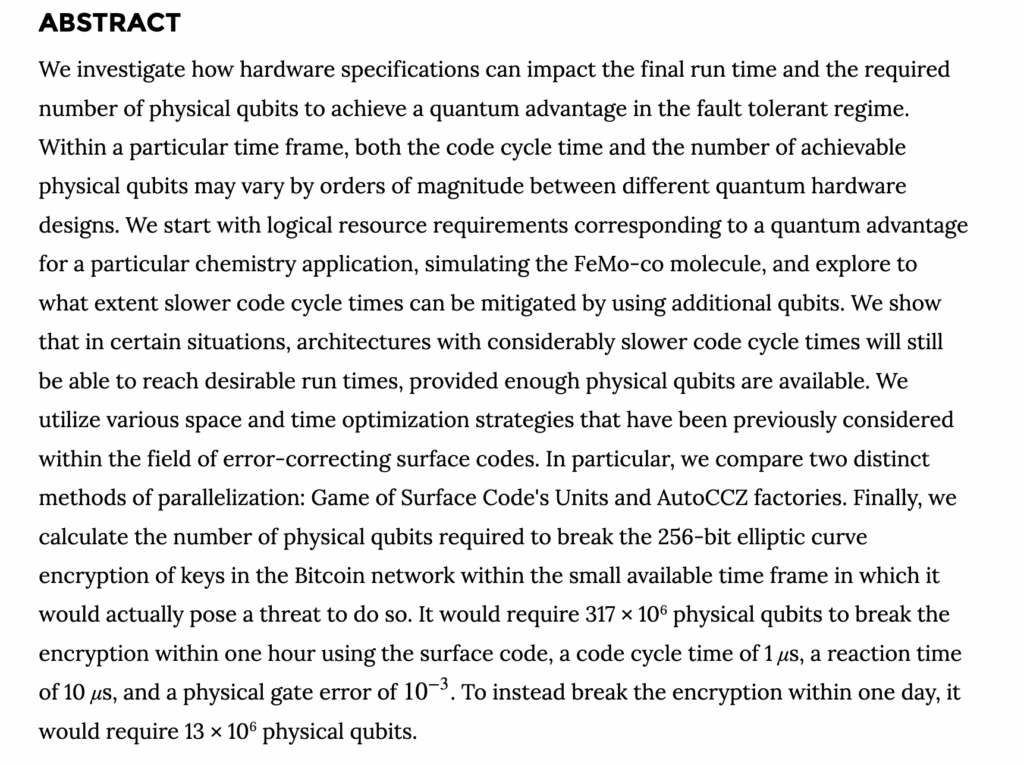

Realism about Quantum computing

Given that our entire digital world increasingly depends on strong and virtually unbreakable encryption, there have been lots of doomsday conjectures about the computational power that will supposedly be provided by ‘quantum’ computers — i.e. those that work with Qubits rather than binary bits. The belief is that quantum machines will be so powerful that they will do in minutes calculations that would take conventional machines millions of years.

This interesting paper seems to throw cold water on this. Here’s the Abstract:

Note the number of physical Qubits required: 317 million to break the Bitcoin encryption in a time period small enough to be operationally useful.

Reality check: At the moment, the biggest working quantum computer (IBM’s) has the princely number of 127 physical Qubits.

Tentative conclusion: Conventional encryption looks a good bet for the time being.

This Blog is also available as a daily email. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!