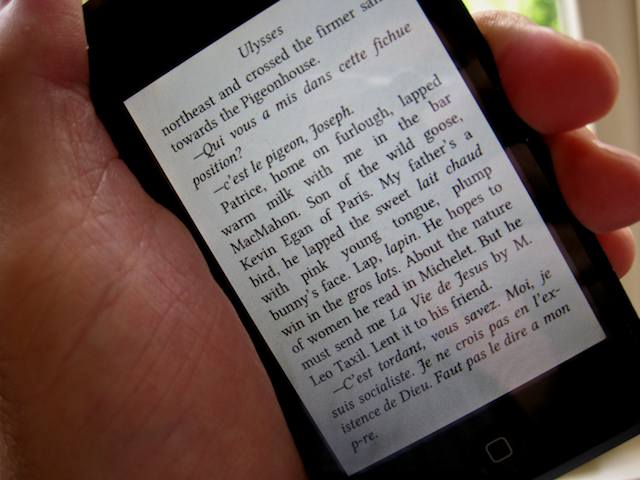

I bought the Eucalyptus iPhone App the other day (for the price of a single paperback book) and suddenly am able to search, download and read everything in the Gutenberg archive. It’s simply wonderful — no other word for it. The text is eminently readable and the interface delightfully simple. As is my wont at this time of year, I’m re-reading Ulysses. But this year instead of lugging around a thick volume, it’s in my shirt pocket. Magical!

Marilyn Moysa (1953-2009)

Photograph courtesy of the Edmonton Journal.

Marilyn Moysa, who was one of the best and toughest reporters I’ve known, has died after fighting a long and determined rearguard action against cancer. In 1992 she came to Wolfson College as a Press Fellow, with an established reputation as a campaigner for journalistic rights. In 1989, as the Labour Reporter of the Edmonton Journal, she had gone all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada to protect her sources. She risked being sent to jail for refusing to testify at a Labour Relations Board hearing, but she wouldn’t back down.

“I think she was apprehensive about how it might turn out, but she had decided in her own mind she wasn’t going to testify,” said the Journal’s lawyer, Fred Kozak, this week. “It was more a matter of principle.”

He went on to say that the case has stood as a warning to anyone wanting to subpoena a reporter.

“To put it bluntly, since then, many, many times we have used ‘Moysa’ to illustrate how seriously the media takes the issue,” he said.

In its obituary, the Journal said that “her stand for journalistic principles continues to shield her colleagues from being dragged into court to reveal their sources. When she died Monday at age 56 after battling cancer for two decades, she left a template for courage and determination, both in life and in her work.”

I remember Marilyn as a passionate, warm, funny and intelligent journalist. She came to Wolfson to study the changing legal climate around assisted human reproductive technology. (Cambridge was a pioneering centre of research and practice in the area at the time.) After she returned to Canada she was diagnosed with breast cancer and she kept us awestruck and moved by her annual dispatches from the chemotherapy battlefield. She was one of those life-enhancing people who left the world a better place than when she found it. I feel privileged to have known her. May she rest in peace.

Net neutrality and BT

I’m not a BT Broadband customer. Well, not directly. My home DSL service is supposedly provided by Pipex — which, when I last looked, had been acquired by Tiscali. But I am indirectly a BT customer because (a) they provide the phone line, and (b) they are the broadband wholesaler for Pipex/Tiscali. I’m paying for a service which theoretically offers 8mbps but in practice has never delivered anything better than 3mbps — against a theoretical maximum of 4mbps because of the distance between my home and the exchange. (I live in a village.)

I find the BBC iPlayer invaluable. But it’s often flaky. And HD is completely beyond my connection. Until I read this I was resigned to putting this down to the laws of physics.

BT Broadband cuts the speed users can watch video services like the BBC iPlayer and YouTube at peak times.

A customer who has signed on to an up to 8 megabit per second (MBPS) package can have speed cut to below 1Mbps.

A BT spokesman said the firm managed bandwidth “in order to optimise the experience for all customers”.

The BBC said it was concerned the throttling of download speeds was affecting the viewing experience for some users. Customers who opt for BT’s Option 1 broadband deal will find that the speed at which they can watch streaming video is throttled back to under 1Mbps between 1700 and midnight.

The BBC iPlayer works at three different speeds, 500Kbps, 800Kbps, and 1.5Mbps, depending on the speed of a user’s connection. There is also a high definition service which requires 3.2Mbps. Sources at the BBC said the effect of BT’s policy was to force viewers down on to the 500Kbps service, which can make the viewing experience less satisfactory.

I’ve just checked the speed of my collection at 6.15pm on a Friday evening. I’m getting only 1.78mbps. Hmmm… Time to investigate further. First stop, Pipex.

Labour’s National Security State: update

From the British Journal of Photography.

The Home Office has rejected a Freedom of Information Act request filed by the BJP regarding the disclosure of the list of all areas where police officers are authorised to stop-and-search photographers under Section 44 of the Terrorism Act 2000.

The controversial Act of Parliament, put into force in 2001, allows Chief Constables to request authorisation from the Home Secretary to define an area in which any constable in uniform is able to stop and search any person or vehicle for the prevention of acts of terrorism. The authorisation, which can be given orally, must be renewed every 28 days and only covers the areas specified in the Chief Constables’ requests.

While it is common knowledge that the entire City of London, at the behest of the Metropolitan Police, is covered by the legislation, it remains unclear which other areas in England and Wales have requested the stop-and-search powers.

After growing concerns from BJP readers, some of whom say they have been abusively stopped from taking pictures around the country, news editor Olivier Laurent filed a Freedom of Information Act request to the Home Office on 24 April. The request asked for a ‘full list of all areas – in England, Wales and Northern Ireland – subject to Section 44 Terrorism Act 2000 authorisations, which the Home Office has a statutory duty to be aware of.’

The request was rejected in late May on grounds of national security. ‘In relation to authorisations for England and Wales, I can confirm that the Home Office holds the information that you requested. I am, however, not obliged to disclose it to you,’ writes J Fanshaw of the Direct Communications Unit at the Home Office. ‘After careful consideration we have decided that this information is exempt from disclosure by virtue of Section 24(1) and Section 31(1)(a-c) of the Freedom of Information Act.’

‘Section 24(1) provides that information is exempt if required for the purposes of safeguarding National Security. Section 31(1)(a-c) provides that information is exempt if its disclosure would, or would be likely to, prejudice the prevention or detection of crime, the apprehension or prosecution of offenders, or the administration of justice.’

The Home Office continues: ‘In considering the public interest factors in favour of disclosure of the information, we gave weight to the general public interest in transparency and openness. This was considered in balance with not disclosing the information due to law enforcement and National Security issues.’

According to the Home Office’s Direct Communications Unit, the disclosure of a Section 44 authorisation in a particular area is an operational matter for the police force covering that area. ‘The Home Office believes that as Section 44 authorisations are used with up to date intelligence, to make any specific authorisation public could inadvertently release sensitive information. A list of authorisations that are in place could also allow any terrorists to act outside of them…

Kafka, where are you when we need you?

The real cost of staying connected

Useful analysis of the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) of (reading from left to right): iPhone 3Gs, Palm Pre and G1 Android — in the US.

[Source.]

Networked journalism

Lest the print media get too carried away by the ‘success’ of the Daily Telegraph’s revelations about MPs’ expenses, it’s worth recalling where all this stuff started. Charlie Beckett has a thoughtful post about this. Excerpt:

The independent MySociety website They Work For You has been providing non-partisan data on what MPs are doing for years, run by volunteers. Earlier, this year it created a Facebook campaign site to force the government to reveal the details of MPs’ expenses. The story had originally been set running by freelance journalist Heather Brooke who had tried to get details of MP’s expenses through the new Freedom Of Information powers created a few years ago by this Labour Government. Among the northern Continental states you are familiar with the concept of open government but this is a novelty in the UK. The system resisted Brooke’s requests and, indeed, MPs were on the verge of ruling against transparency on the details of their claims. The MySociety initiative played a critical part in reversing this policy of secrecy by revealing this manouvere which had been largely ignored by the mainstream media. Now the Daily Telegraph has paid for the CD-Rom which gave them all the details anyway. The story has exploded from a small but significant online campaign to a massive media story that threatens to bring down this government and has undermined faith in the whole parliamentary political system. That, my friends, is what I call Networked Journalism.

The way forward: anti-chaos engineering

Just reading one of those “How I Work” pieces by Matt Mullenweg — the WordPress guy. “I’m very disorganized”, he writes. “I’m wildly late all the time and really bad at keeping a schedule. That is one of the many reasons I love Maya [Desai]. Her official title is ‘anti-chaos engineer’, which is another way of saying office manager.”

Yep. I could use one of those.

French judges deem Internet access a fundamental human right

Good news (for once) in the Daily Mail.

Access to the internet is a human right, claim France’s most senior lawmakers.

The web was “an essential tool for the liberty of communication and expression”, according to the Constitutional Council.

It was ruling on legislation against pirates stealing copyrighted music, video and films from the Net…

China’s “Green Dam” censorware opens the door to malware

From Technology Review.

Controversy erupted this week over reports that the Chinese government plans to require all computers sold in the country to come with software that screens for objectionable websites. Although initial criticism came from privacy advocates and those most concerned about censorship, experts have also now found that the software could introduce critical security risks to computers across the country.

According to the BBC, the software communicates in plain text with central servers at its parent company. Not only does this potentially place personal information in the hands of eavesdroppers, but it could also allow hackers to take over PCs running the software, creating a massive zombie network that could deliver spam or attack other computers across the globe…

Ed Felten has followed up on this, drawing attention to an investigation by security researchers which confirms the story. Ed concludes:

This is a serious blow to the Chinese government’s mandatory censorware plan. Green Dam’s insecurity is a show-stopper — no responsible PC maker will want to preinstall such dangerous software. The software can be fixed, but it will take a while to test the fix, and there is no guarantee that the next version won’t have other flaws, especially in light of the blatant errors in the current version.

Schadenfreude: the new black

At lunch in College today we had an interesting discussion with a visiting Iranian journalist about the hypocrisy of Western countries trying to deny to some countries (e.g. Iran) the right to developments that the Western democracies take for granted for themselves. And then I came home and found this riveting piece by Joseph Stiglitz. One passage in particular caught my eye:

Among critics of American-style capitalism in the Third World, the way that America has responded to the current economic crisis has been the last straw. During the East Asia crisis, just a decade ago, America and the I.M.F. demanded that the affected countries cut their deficits by cutting back expenditures—even if, as in Thailand, this contributed to a resurgence of the aids epidemic, or even if, as in Indonesia, this meant curtailing food subsidies for the starving. America and the I.M.F. forced countries to raise interest rates, in some cases to more than 50 percent. They lectured Indonesia about being tough on its banks—and demanded that the government not bail them out. What a terrible precedent this would set, they said, and what a terrible intervention in the Swiss-clock mechanisms of the free market.

The contrast between the handling of the East Asia crisis and the American crisis is stark and has not gone unnoticed. To pull America out of the hole, we are now witnessing massive increases in spending and massive deficits, even as interest rates have been brought down to zero. Banks are being bailed out right and left. Some of the same officials in Washington who dealt with the East Asia crisis are now managing the response to the American crisis. Why, people in the Third World ask, is the United States administering different medicine to itself?

Many in the developing world still smart from the hectoring they received for so many years: they should adopt American institutions, follow our policies, engage in deregulation, open up their markets to American banks so they could learn “good” banking practices, and (not coincidentally) sell their firms and banks to Americans, especially at fire-sale prices during crises. Yes, Washington said, it will be painful, but in the end you will be better for it. America sent its Treasury secretaries (from both parties) around the planet to spread the word. In the eyes of many throughout the developing world, the revolving door, which allows American financial leaders to move seamlessly from Wall Street to Washington and back to Wall Street, gave them even more credibility; these men seemed to combine the power of money and the power of politics. American financial leaders were correct in believing that what was good for America or the world was good for financial markets, but they were incorrect in thinking the converse, that what was good for Wall Street was good for America and the world…

This kind of double-thinking hypocrisy pervades all areas of our public life now. Think of Tory MPs claiming for moats and duck houses while taking a stern line on public-sector pay increases. A particularly vivid example is provided by a prominent Irish banker who was eventually shown to be ‘warehousing’ huge (€80 million plus) loans extended to him by the bank of which he was CEO and (later) Chairman. And then some enterprising journalist found a recording of a radio interview this guy had given a few months before being exposed, in which he sternly talked about the need for working people to accept the need to live within their incomes. The whole system stinks.

There’s a nice cartoon accompanying the Stiglitz article. It lists the Four Horsemen of the financial apocalypse: mendacity, stupidity, arrogance and greed.