The nightweb

Pass the double cream (and the butter) and damn the consequences

It’s funny how movies and TV series spark off sales booms in books. (Remember the way an obscure reference to Flann O’Brien in Lost led to a sudden surge in demand for his The Third Policeman?) Well, the movie Julie and Julia has led to Julia Child’s 40-year-old cookbook, Mastering the Art of French Cooking, the tome that introduced the US gastronomic classes to French cuisine, climbing the NYT best-seller lists. And to an outbreak of blogging on the subject. Here’s an example from the NYT report.

Readers who only recently opened the book, and have been blogging and tweeting about it, have found some anachronistic surprises.

“I’m looking at these ingredients going, Oh, sweet Lord, we’ll die,” said Melissah Bruce-Weiner, 45, a resident of Lakeland, Fla., who bought the book on her way home from seeing the movie. Horrified by the prospect of cooking with pork fat, she tried her own variation of boeuf bourguignon, which she called “beef fauxguignon.”

“I know why all of the greatest generation has died of heart attacks,” she said. “I actually did a can of cream of mushroom soup, and a can of French onion soup, and a can of red wine — it was the same can — I filled it with the bottle that I had been drinking the night before.

“Yes, Julia Child rolled over in her grave when I opened the cream of mushroom soup, I’m pretty sure of that. But you know what? That’s our world.”

I’m not a purist, but really — cream of mushroom soup.

Farming today — and yesterday

It’s harvest day on the farm next to where we live. By the standards of my (Irish) childhood, it’s an enormous farm — maybe 300 acres, but by East Anglian standards it’s quite small. It’s owned by the University of Cambridge and our neighbour is therefore a tenant farmer. A century ago it would have employed maybe a dozen labourers, plus the farmer’s able-bodied sons. Now it employs precisely one person — the farmer himself.

All of this is possible because he now grows only cereals, and because of mechanisation. Up to this year, he’s done the harvesting himself, but his combine harvester is now so old, he tells me, that he can only get spares from the scrap dealer. So this year he’s got contractors in to do it, and this is the day they’ve chosen.

They’ve been at it since before dawn. It’s now dark and I’m sitting in the garden listening to the roar of enormous tractors pulling large trailers which, at about ten-minute intervals emerge from the fields loaded with grain. They go back and forth to the combine, load up with the grain that’s been cut and threshed in the intervening period, tip it out and then return to the fields. The house shakes as they thunder past.

Suddenly I’m transported back to my childhood, over half a century ago. We’re in Connemara, where my paternal grandparents were peasant farmers. They owned no machinery but did have a donkey and a cow. They lived in a classic Irish thatched cottage. The heart of the house was a large high-ceilinged kitchen with an open fire which burned turf (i.e. peat). At each gable end of the house there were a few tiny rooms – one a parlour which was never used, as far as I remember, except for laying out the corpse after a death or giving tea to the parish priest on his occasional, ceremonial visits. The other rooms were bedrooms, each with a brass bedstead, a patchwork quilt and a stand with a porcelain basin and a jug.

The kitchen was pretty dark, even in the daytime. On one side there was a door which led out into the yard, where chickens scratched and cackled. (They would have come into the stone-flagged kitchen if there hadn’t been a half-door.) On the other side of the room were two small windows, each with four quadrants of glass. There was no electricity and no running water.

It was the first time I remember staying there. My brother and I had come on a visit with my father — who had escaped from his background because a teacher had spotted his potential and kept him on at school after the statutory leaving age of 14. My mother was staying with my baby sister at her parents’ house, many miles away in Mayo, in the more salubrious setting of a prosperous merchant household.

We were deeply in awe of Da’s parents. They were silent, kindly but stern and spoke only Irish. Grandad (called Daidó) wore classic bainín clothes and hobnail boots; Grandma (called Mamó) wore a shawl when she went out. She also took snuff, which amazed, fascinated and slightly repelled us. They took the view that children should be seen and not heard, so we were correspondingly visible but taciturn. There were no toys of any description in the house.

The day I’m thinking of was in high summer. Daidó owned a small number of fields, most of which were rocky beyond belief. (Not for nothing had Cromwell given my forebears the option of “To Hell or to Connacht”.) But on the road up to the bog Daidó had three fields which had been largely cleared of rocks and were essentially smallish meadows. My father and he disappeared early in the morning, just after dawn. At about 10.30 in the morning, my brother and I were given large jugs of buttermilk covered with muslin, together with loaves of sodabread, and told to bring them up to the fields. When we got there we found a large group of men, maybe a dozen in all, moving through the fields with scythes, cutting the grass. They stopped when they saw us coming, gathered round and drank and ate without saying much. To us they said absolutely nothing.

We returned to the cottage. There was absolutely nothing to do. Mamó busied herself in various farmyard chores. My brother and I mooched about the duckpond in the centre of the cluster of houses which made up the tiny hamlet. The entire settlement was deathly quiet, baking in the sunshine. The day seemed interminable. Evening came and, to our surprise, we were not sent off to bed. At about 10pm we watched as Mamó scrubbed a huge pile of potatoes and put them into a large black pot which she suspended over the open fire. She then lit the oil lamps. When the potatoes were cooked, she turned them out into a huge basket, where they lay steaming. She then fetched a block of salted butter and jugs of buttermilk from the little lean-to dairy outside the house, and sat by the fire taking snuff.

In that part of the west of Ireland, it doesn’t get really dark until nearly 11pm in June. But as the light was fading, the door of the cottage opened and in filed the group of men who had been working with Da and Daidó in the fields. They said very little, just sat around the walls of the kitchen on chairs. Each was given a plate with floury potatoes and glistening knobs of melting butter. And a cup of buttermilk. They ate quietly. There was an occasional murmur of conversation, but what I remember most was the quiet munching of tired men. Then, without saying much, they got up and walked out into the glow of a midsummer night.

This was my first glimpse of the meitheal system, in which peasant farmers with no access to machinery would combine to help each other with the harvest. Tomorrow my grandfather would go to one of their fields and return the compliment. And we would return to the world of mains electricity and running water.

Viewed from the perspective of this evening, when the rumble of heavily-laden tractors still rattles our windows, and one man can run a 300-acre farm, this memory seems as distant as the middle ages. And yet it’s a vivid recollection of a lived experience. This is what the ‘Celtic tiger’ was like within living memory — a country as poor and as backward as parts of Albania are today.

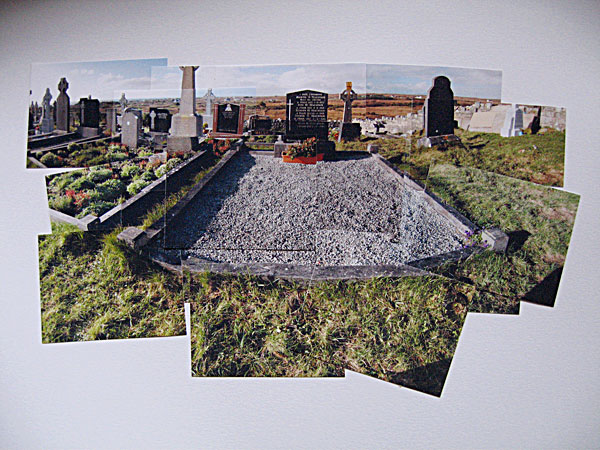

Many years after that first visit to my grandparents, Sue and I visited the graveyard where they are buried. (They died in the 1970s within 24 hours of one another, both aged 94.) It’s a lovely, peaceful place which looks out over Galway Bay and the Aran islands. But it’s also contains a sharp reminder of what progress means: the family plot shows that in the space of a single terrible year Mamó and Daideó lost three of their nine children to those infectious diseases which once cut a swathe through every family in rural Ireland. Two of the children died within a week of one another. Modernity may have its discontents. But it also has its consolations.

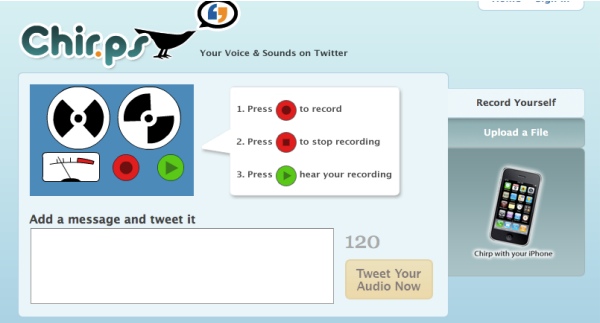

Feeling Chirpy?

Latest addition to the Twitter ecosystem. You can find it here.

Now you see it, now you don’t.

This morning’s Observer column about the power that Google now wields.

Most of the time we don’t think about this because the company provides such a useful service to the average web user. But if you look at it from the point of view of someone who runs an online business then you get a very different perspective. In The Search, an excellent book about Google, John Battell tells a story that illustrates this perfectly.

It concerns a small entrepreneur called Neil Montcrief, who in 2000 founded a small e-commerce business (2bigfeet.com) selling outsize shoes on the net. For a time, the business was modestly prosperous because of the traffic Google drove to Montcrief’s site. By the middle of 2003 he was shifting $40,000 of big shoes a month.

“And then, one day in November of that year, everything changed. Traffic to his site shrivelled, cash flow plummeted and Montcrief fell late on his loan payments. He began avoiding the UPS man, because he couldn’t pay the bill. His family life deteriorated. And, as far as Montcrief could tell, it was all Google’s fault.”

In a sense, it was. But Google had not targeted him: the vaporisation of his little business turned out to be just collateral damage in the ceaseless war between Google and the armies of people who try to ‘game’ its search results…

Research Bureau

From today’s Irish Times.

GERMAN RESEARCHERS have discovered a scientific basis for one of the hoariest of horror film cliches.

It’s a familiar scene. A group of teenagers get lost and wander aimlessly through the forest until, just before the knife-wielding maniac appears, one teenager asks: “Haven’t we been this way before?”

Now researchers at Germany’s prestigious Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics have discovered that, when they lack clear landmarks, humans do indeed walk in circles.

The German team examined the paths taken by volunteers wearing GPS tracking devices in a dense forest near the French border and in the Sahara desert.

On days with clear conditions, volunteers kept a straight path – though they often veered from straight ahead – while in cloudy conditions, they began wandering in circles without realising.

Pshaw! Research my eye. This is Old Hat, as anyone who has read A.A. Milne knows. They will recall the story (‘Tigger is unbounced’) in which Rabbit, who is not exactly enamoured of Tigger at first, conceives a plan to take the newcomer for a walk in the fog and then lose him. They do indeed lose him, but then discover that they are walking round in circles under Rabbit’s confident leadership.

Fancy all those Herr Doktors at the Max Planck Institute not knowing that there was Prior Research in this subject. Huh!

Apple ‘Still Pondering’ Google Voice App for the iPhone

Hmmm… New York Times reports that

Apple told the Federal Communications Commission on Friday that it did not reject an iPhone application submitted by Google and that it was still studying it, in part because of privacy concerns.

Apple was formally responding to a commission inquiry into the reason the Google Voice service, which offers users free domestic telephone calls, deeply discounted international calls and SMS messages, had not been allowed into the Apple iPhone App Store.

Apple said in a letter to the F.C.C. that Google Voice duplicated the functions of the iPhone, which uses the AT&T network in the United States, and might confuse users. The application “appears to alter the iPhone’s distinctive user experience by replacing the iPhone’s core mobile telephone functionality and Apple user interface with its own user interface for telephone calls, text messaging and voice mail,” the letter said.

Apple also raised concerns that Google Voice copied all of the information about a user’s contacts onto Google’s servers. “We have yet to obtain any assurances from Google that this data will only be used in appropriate ways,” the letter said.

Interestingly, Apple said that it had not discussed the Google Voice App with AT&T and that in most cases “its contract with the wireless carrier gave it the sole authority to decide whether to accept applications”. But is also admitted that it had agreed “not to allow any applications that sent voice calls over the Internet, bypassing AT&T’s network, without the phone company’s permission”. This explains why services like Skype were allowed by Apple — they used only Wi-Fi connections, not AT&T’s network. So the problem with the Google Voice App may be that it doesn’t send calls over the Internet but connects to both parties over the telephone network.

This isn’t over yet. It’ll be interesting to see the FCC’s response.

Don’t put your faith in the Cloud

Typically thoughtful post by Dave Winer.

I’m worried about the web.

We pour so much passion into dynamic web apps hosted by companies we know very little about. We do it without retaining a copy of our data. We have no idea how much it costs them to keep hosting what we create, so even if they’re public companies, it’s very hard to form an opinion of how likely they are to continue hosting our work.

A few weeks ago an entrepreneur said to my face that he was the one who made the money and I was the one who worked for free. My chin dropped. I knew most if not all of them secretly believed this, but I had never heard one say it out loud.

I know others who told me their business model was to patent my work.

Shaking my head. This can’t work.

This system is terrible. It’s a bubble, like the real estate bubble. It’s going to burst, and when it does, it will take a lot of our history with it.

But not this blog post if I have any say about it. It’s stored as a static file on a Windows XP server running Apache. It could just as easily be stored on a Linux machine running anything. Or even an iPod or iPhone. Text files are the ultimate in stability. The same text file you could read on a mainframe 40 years ago could be read on a netbook today. ‘

I’ll post a link to this piece on Twitter, that probably won’t last very long. But — the backup I’m making of it is being stored as a static text file on Apache. So it may well be around for a while.

I’m really obsessed with creating a historic record. I want to feel that our writing has a future. I also don’t want to work for people who are as openly greedy as the typical entrepreneur of 2009.

Yep. Mine is backed up too on a local machine or two. (It’s only about 20MB and therefore trivial to do. Instructions for wordpress.com hosted blogs can be found here. If you want to back up your own WordPress installations go to ../wp-admin/export.php and click on ‘Download Export File’.) Likewise I have copies on several local drives of all the photographs I’ve ever posted to Flickr. And all of my Google docs.

How about you?

Conciergery

The livelihood of a hotel concierge depends on the maintenance of a complex facade: traditionally, he must be obsequious yet peremptory; menial and, at the same time, a bit of a snob. This makes the inner life of the concierge, like that of the psychiatrist or the pastor, the object of speculation. In Muriel Barbery’s novel The Elegance of the Hedgehog, a dumpy concierge nurses a private devotion to Tolstoy. In the 1993 movie For Love or Money, the concierge Doug Ireland (played by Michael J. Fox) must endure the whims, and walk the poodles, of such guests as Mr. Salvatore, who keeps asking for more of “dem things on the pillow,” by which, Doug finally figures out, he means mints.

From a delicious piece by Lauren Collins in the current New Yorker.