I’m three days into my iPad experiment (and writing The iPad Diaries as I go). Interesting to see that Jeff, with his characteristic decisiveness, has already acted.

Spot the balls

The madness begins. Lovely piece by Emine Saner in today’s Guardian. It seems that England’s spoilsport manager Fabio Capello has limited the access his players will have to their wives and girlfriends to one day after each game, with further restrictions should the team progress.

“There is a historic element that has become a kind of mythology in sport,” says Greg Whyte, professor of applied sport and exercise science at Liverpool John Moores University. “The Ancient Greeks believed that sex was detrimental in the build up to the Olympics – that it sapped energy, lowered test-osterone and reduced aggression. But research runs counter to this. There have been a few studies on sex before sport and they have shown it has no effect on performance. However, sleep quality is crucial in terms of performance and sex can enhance sleep, so therefore it may enhance performance.” Unless it’s preventing them getting any sleep.

But it seems that not all teams are facing a sex ban. Argentina’s team doctor Donato Villani was reported in the Sun (where else?) last week as saying:

“Sex is a normal part of social life and is not a problem. The disadvantages are when it is with someone who is not a stable partner or when the player should be resting.” It is very important, he notes, that “the action should not reverberate in the legs of the players.”

Quite so. I’m depressed about this. One of the most entertaining aspects of the last World Cup was the spectacle of the England Wags wandering like a cloud through a host of upmarket shopping malls.

It’s television, Eric, but not as we know it

This morning’s Observer column.

And now for something completely different: Google TV. Yes, you read that correctly: Google TV. Now I know what you’re thinking. You already have enough TV channels, most of them running Friends, Desperate Housewives or reruns of Top Gear. Why on earth would you want to watch a channel in which a T-shirted nerd with an IQ in the low thousands explains how to code an algorithm for complex linear programming in seven lines of Perl while behind him one of his more subversive colleagues is gleefully demonstrating on a whiteboard how it can be done in four?

Relax. Google TV is not a channel, it’s a platform, ie a base on which things can be built. In ordinary life, platforms are physical objects, such as the drilling rig that is causing BP such grief, but the Google guys don’t do physical. They’re geeks, so their idea of a platform is a large piece of software called an operating system. A while back, they created such a platform for mobile phones…

Quote of the day

“Men are esteem engines; women are perpetual emotion machines.”

From the Guardian‘s obituary of Richard Gregory, the late, great neuroscientist .

Why Facebook’s privacy problem may be fatal

Everything you need to know in a nutshell. From Bruce Nussbaum, writing in the Harvard Business Review.

Facebook’s imbroglio over privacy reveals what may be a fatal business model. I know because my students at Parsons The New School For Design tell me so. They live on Facebook and they are furious at it. This was the technology platform they were born into, built their friendships around, and expected to be with them as they grew up, got jobs, and had families. They just assumed Facebook would evolve as their lives shifted from adolescent to adult and their needs changed. Facebook s failure to recognize this culture change deeply threatens its future profits. At the moment, it has an audience that is at war with its advertisers. Not good.

Here’s why. Facebook is wildly successful because its founder matched new social media technology to a deep Western cultural longing — the adolescent desire for connection to other adolescents in their own private space. There they can be free to design their personal identities without adult supervision. Think digital tree house. Generation Y accepted Facebook as a free gift and proceeded to connect, express, and visualize the embarrassing aspects of their young lives. Then Gen Y grew up and their culture and needs changed. My senior students started looking for jobs and watched, horrified, as corporations went on their Facebook pages to check them out. What was once a private, gated community of trusted friends became an increasingly OPEN, public commons of curious strangers. The few, original, loose tools of network control on Facebook no longer proved sufficient. The Gen Yers wanted better, more precise privacy controls that allowed them to secure their existing private social lives and separate them from their new public working lives.

Facebook’s business model, however, demands the opposite…

Worth reading in full.

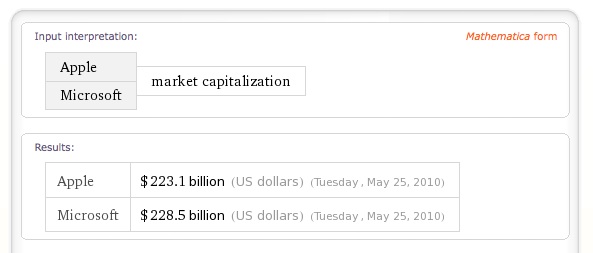

Apple & Microsoft: the gap narrows

The parallels don’t stop here, either. It seems that the anti-trust guys in the Department of justice are beginning to take an interest in Mr Jobs’s plucky little company.

Web science institute goes phut: “Low priority” says coalition

From BBC News.

Funding for a new Institute for Web Science, set up with a £30m grant from the department for Business, Innovation and Skills (Bis) has been cut.

The collaboration between the Universities of Oxford and Southampton, announced in March 2010, was led by web creator Sir Tim Berners-Lee and Professor Nigel Shadbolt.

Both are also leading the government’s open data project data.gov.uk.

BIS said it was a “low priority” as it announced its efficiency savings.

The cut is part of Chancellor George Osborne’s plans to make £6.2bn savings in order to reduce the budget deficit.

A spokesperson from Bis said that the government remained committed to investing in internet technology research elsewhere but that it “cannot support” the creation of the institute in the current economic climate.

Apple: the little company that’s almost as big as Microsoft

Behind the Digger’s Paywall

The FT has an interesting peek behind the impending Murdoch paywall.

“It looks a lot like a newspaper, which I don’t think we’re apologising for,” said Tom Whitwell, assistant editor of the Times. “The article pages we think are simple and clean, and easy to read.”

He talks of a “news hierarchy”, with fewer stories thrown at the reader than most newspaper websites. “We are not going to show you all the news,” he says, comparing that favourably with “Google News showing you 4,000 versions of the same thing. We are giving you our take on the news.”

The Times’ stories will not be among those 4,000, with not even a headline visible in the Google index (or indeed that of any other search engine). Peculiarly, the existing TimesOnline site will live on after the paywall goes up for an indeterminate time, although it won’t be updated – an admission, perhaps, of how baked into the web its links already are.

The funniest thing in the piece is the burbling of Danny Finkelstein, the engaging Times Comment Editor:

“We can project the Times with all its tradition and iconography, but on the web,” he enthused.

Few of the Times employees presenting their plans used the word ‘paywall’ unprompted. But Mr Finkelstein insisted this barrier would not prevent him from sharing links to his articles on Twitter or cut the newspaper out of a wider online conversation. Rivals without the protection of a paywall “won’t go viral, they will go out of business”, he said.

Although there were hints that extracts might occasionally be visible to non-subscribers in the future, the Times’ content will remain tightly locked up with not even a first paragraph to tease in new customers. This apparently aids the “clarity” of the offering, in contrast to the less binary model offered by the Wall Street Journal and the FT.

“We are unashamed about this,” said Mr Finkelstein. “We are trying to make people pay for the journalism…. I want my employer to be paid for the intellectual property they are paying me for.”

Aw, shucks. It was nice knowing these guys. But I guess they’ll find jobs outside the paywall.

I liked what Steve Hewlett said about it on the Today programme this morning. To paraphrase him, everyone in the newspaper business is cheering them on and hoping it will work — but thinking that it won’t.

tblair@khoslaventures.com – the new tech guy on the block

Truly, you couldn’t make this up.

SAUSALITO, Calif. — Tony Blair, the former British prime minister, is turning his attention to Silicon Valley. Mr. Blair is becoming a senior adviser at Khosla Ventures, the venture capital firm founded by Vinod Khosla, an investor and a proponent of green technology.

Khosla Ventures, which Mr. Khosla founded in 2004 after leaving the venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, made the announcement here on Monday at a meeting of its investors. The firm is investing $1.1 billion in clean technology and information technology companies.

Mr. Blair will offer strategic advice on public policy to the firm’s green portfolio companies. They include Calera, a manufacturer that uses carbon dioxide to create cement products; Kior, which converts biomass like wood chips into biofuels; and Pax Streamline, which aims to make air-conditioning more environmentally friendly.

“The more I studied the whole climate change issue and linking it with energy security and development issues, I became absolutely convinced that the answer is in the technology,” Mr. Blair said in an interview.

You know what this appointment reminds me of? Mike Lynch’s decision to appoint Richard Perle (aka the US Prince of Darkness) to the Board of Autonomy.