Spotted in the entrance hall of Cambridge University Library. Who says eggheads aren’t interested in football!

Oops

From a blog post by Dan Ariely entitled “7 Habits of Highly Ineffective People”.

Cape Cod is tweeting

Interesting glimpse of what you can do with a combination of sensors and Twitter. From Tech Review.

If you want to know whether or not the tides are high enough to get your sloop out of Ockway Bay in Cape Cod, you could consult NOAA's tide tables. Trouble is, less'n you're a pipe-smoking old-timer who's handy with the lobster cages and a sextant, they're as likely to get you stuck going in and out of the bay as they are to tell you, with sufficient accuracy, whether the already-shallow draft below your boat is enough to let you safely navigate the muddy shoals of your home port.

That's where the internet comes in, and not the kind that's stuck behind a desk, twiddling with an iPad – we're talking about the Internet of Things. Using an ultrasonic level sensor to bounce sound waves off the sea surface in order to determine its height, an XBee radio to send that data to a receiver on shore, and most importantly, an ioBridge IO-204 to relay that information to servers in the cloud, Cape Cod resident and ioBridge hobbyist Robert Mawrey is able to broadcast to his entire community near real-time data on actual sea level.

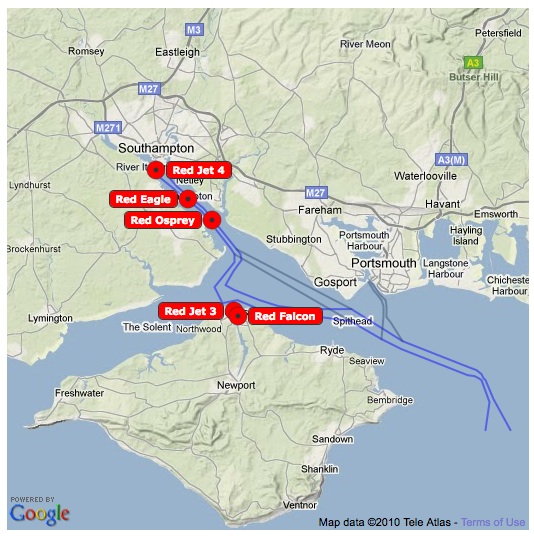

Actually, in this particular case, the Americans are just catching up. See, for example, the stuff that Andy Stanford-Clark has been doing with south coast ferries.

Tony Blair, technophile (for a fee)

This morning’s Observer column.

“Blair to join venture firm as adviser on technology” said the headline in the New York Times. Eh? The first thing that came to mind is the celebrated story of the emperor Caligula and his attempts to have his horse, Incitatus, appointed as a consul. Anyone familiar with our former prime minister’s encounters with technology one thinks, for example, of the time he tried to order flowers for Cherie over the web will have been puzzled by this development. Tony has many talents, but the one thing he doesn't do is technology.

So who’s playing Caligula in this particular farce? Answer: Vinod Khosla, an Indian-American venture capitalist with impeccable academic and technology credentials, who now runs a $1bn fund that invests in ‘green’ technology aka cleantech and IT…

The economics of peer review

My Open University colleague Martin Weller has done some interesting calculations of the cost of the academic peer-review process.

Peer-review is one of the great unseen tasks performed by academics. Most of us do some, for no particular reward, but out of a sense of duty towards the overall quality of research. It is probably a community norm also, as you become enculturated in the community of your discipline, there are a number of tasks you perform to achieve, and to demonstrate, this, a number of which are allied to publishing: Writing conference papers, writing journal articles, reviewing.

So it's something we all do, isn't really recognised and is often performed on the edges of time. It's not entirely altruistic though – it is a good way of staying in touch with your subject (like a sort of reading club), it helps with networking (though we have better ways of doing this now don't we?) and we also hope people will review our own work when the time comes. But generally it is performed for the good of the community (the Peer Review Survey 2009 states that the reason 90% reviewers gave for conducting peer review was "because they believe they are playing an active role in the community")

It’s a labour that is unaccounted for. The Peer Review Survey doesn’t give a cost estimate (as far as I can see), but we can do some back of the envelope calculations. It says there are 1.3 million peer-reviewed journals published every year, and the average (modal) time for review is 4 hours. Most articles are at least double-reviewed, so that gives us:

Time spent on peer review = 1,300,000 x 2 x 4 = 10.4 million hours

This doesn’t take into account editor’s time in compiling reviews or chasing them up, we’ll just stick with the ‘donated’ time of academics for now. In terms of cost, we'd need an average salary, which is difficult globally. I’ll take the average academic salary in the UK, which is probably a touch on the high side. The Times Higher gives this as £42,000 per annum, before tax, which equates to £20.19 per hour. So the cost with these figures is:

20.19 x 10,400,000 = £209,976,000

Martin points out the implication of this — that academics are donating over £200 million a year of their time to the peer review process. “This isn’t a large sum when set against things like the budget deficit”, he continues,

“but it’s not inconsiderable. And it’s fine if one views it as generating public good – this is what researchers need to do in order to conduct proper research. But an alternative view is that academics (and ultimately taxpayers) are subsidising the academic publishing to the tune of £200 million a year. That’s a lot of unpaid labour.

Now that efficiency and return on investment are the new drivers for research, the question should be asked whether this is the best way to ‘spend’ this money? I’d suggest that if we are continuing with peer review (and its efficacy is a separate argument), then the least we should expect is that the outputs of this tax-payer funded activity should be freely available to all.

And so, my small step in this was to reply to the requests for reviews stating that I have a policy of only reviewing for open access journals. I’m sure a lot of people do this as a matter of course, but it’s worth logging every blow in the revolution. If we all did it….”

Yep.

iPad ergo sum

Going the distance

So who’s really behind the anti-BP hysteria in the US?

The answer, as hinted in this NYTimes piece, is Exxon, which sees a once-in-a-lifetime chance to exterminate a commercial rival.

The idea that BP might one day file for bankruptcy, particularly as part of a merger that would enable it to cordon off its liabilities from the spill, is starting to percolate on Wall Street. Bankers and lawyers are already sizing up potential deals (and counting their potential fees).

Given the plunge in BP’s share price — the company has lost more than a third of its value since Deepwater Horizon blew — some bankers and analysts say BP is starting to look like takeover bait. The question is, who would buy BP, given its enormous potential liabilities?

Shell and Exxon Mobil are both said to be licking their chops. And already, flinty legal minds are dreaming up scenarios in which BP would file a prepackaged bankruptcy and separate the costs of the cleanup — and potentially billions of dollars in legal claims — into a separate corporate entity.

The Wired parenting problem

Interesting (and sobering) piece by Julie Scelfo in today’s NYT.

Much of the concern about cellphones and instant messaging and Twitter has been focused on how children who incessantly use the technology are affected by it. But parents’ use of such technology — and its effect on their offspring — is now becoming an equal source of concern to some child-development researchers.

Sherry Turkle, director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Initiative on Technology and Self, has been studying how parental use of technology affects children and young adults. After five years and 300 interviews, she has found that feelings of hurt, jealousy and competition are widespread. Her findings will be published in “Alone Together” early next year by Basic Books.

In her studies, Dr. Turkle said, “Over and over, kids raised the same three examples of feeling hurt and not wanting to show it when their mom or dad would be on their devices instead of paying attention to them: at meals, during pickup after either school or an extracurricular activity, and during sports events.”

Dr. Turkle said that she recognizes the pressure adults feel to make themselves constantly available for work, but added that she believes there is a greater force compelling them to keep checking the screen.

“There’s something that’s so engrossing about the kind of interactions people do with screens that they wall out the world,” she said. “I’ve talked to children who try to get their parents to stop texting while driving and they get resistance, ‘Oh, just one, just one more quick one, honey.’ It’s like ‘one more drink.’ ”