Seen in Versailles. Flickr version here.

The family that prays together…

… makes a mobile phone call individually.

Spotted outside the cathedral in Versailles. Flickr version here.

Really?

Retiring (but not withdrawing) gracefully

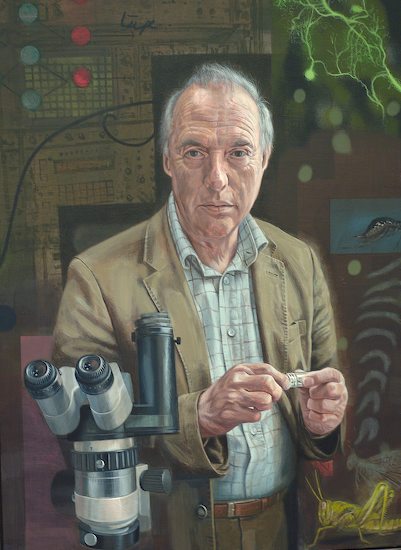

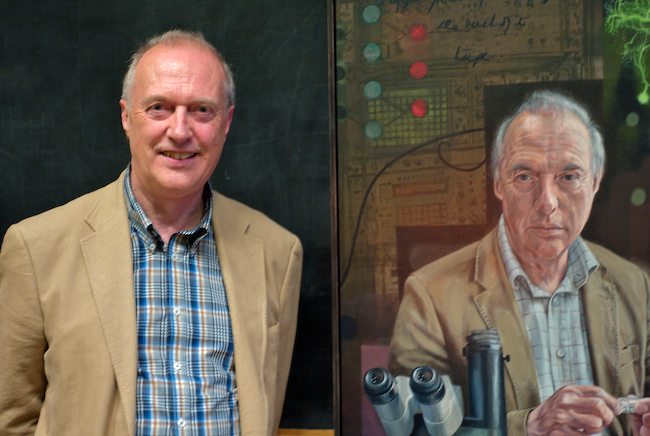

My friend and Wolfson colleague Malcolm Burrows is retiring from his position as Head of the Department of Zoology in Cambridge, and his colleagues put on a whole day of talks to mark the occasion. Even the Vice Chancellor showed up — to explain how, shortly after her arrival in Cambridge, Malcolm had managed to persuade her to do something she hadn’t wanted to do “without ever raising his voice”. (The visit that resulted from that conversation, incidentally, led to an endowed Chair in his Department.) At the end of her speech, she unveiled the portrait by Tom Wood (who did the National Portrait Gallery’s portrait of David Hockney) which has been commissioned to honour him.

Malcolm is one of the cleverest, nicest and sanest people I know. Unlike many high-profile academics, he doesn’t do histrionics. Yet during his tenure, the Cambridge department became the best Zoology department in the country, and one of the best in the world. Unusually for such a large, high-octane outfit it also seems remarkably friendly. Certainly there was a lovely, affectionate tone to the day’s proceedings.

Malcolm’s speciality is neurophysiology — more specifically the neuronal mechanisms by which a nervous system generates and controls natural movements (top right in the portrait). His chosen animals are insects, including some (locusts) that you wouldn’t want to meet on a dark night (bottom right in the portrait). One of his colleagues captured his character neatly when he said that he combined a childlike delight in insects with a very grown-up style of administration. During his tenure, for example, the University’s central authority (the General Board) agreed to write off a huge ancient debt which had for decades “squatted like a huge black toad” on the Department’s back. And, believe me, the General Board didn’t get where it is today by writing off departmental ‘debts’.

It was a really nice occasion which reminded one firstly, of how important people are, even in prestigious institutions, and secondly, what a difference good leadership makes. Most of all, it was reassuring to know that, tomorrow, Malcolm will be back in his lab. He may be technically ‘retired’, but most people wouldn’t guess that.

Before I left, I asked him to pose with his portrait. Here’s the result.

Computers and children’s brains: good news and bad news

There’s an interesting article in the (open access) journal Neuron which summarises a lot of research on the cognitive and neurophysiological impact of computers on kids. The abstract is here. Christopher Mims has done a useful summary of the main points:

* Video game consoles are going to make your kids stupider in the following way: owning one will significantly reduce reading and writing skills — “more than one-half of a standard deviation in the case of writing,” says the paper. (source) This is not just a correlation: it has been established (in at least this one study) causatively.

* “Action” video games can produce better surgeons (source) and pilots (source). They also enhance top-down control of attention, allow players to choose among different options more rapidly (source), increase short-term visual memory (source) and increase flexibility in task-switching. NASA has even considered using them to treat attentional problems in children.

* Television is a model for what we can expect from games designed both for entertainment and education. Multiples studies have shown that Sesame Street increases language and numerical ability in children, while Teletubbies actually decreases language ability in very young children. Likewise, the “Baby Einstein” products were also shown to make children less capable. After controlling for other factors, amount of television exposure as a young child does not generally correlate (in either direction) with later abilities – unless it’s trading off with other critical activities (like opportunities to absorb language through normal socialization).

* Many educational games have no positive effect on learning when used in an education context, but a handful have been proven to work – especially in the area of mathematical education.

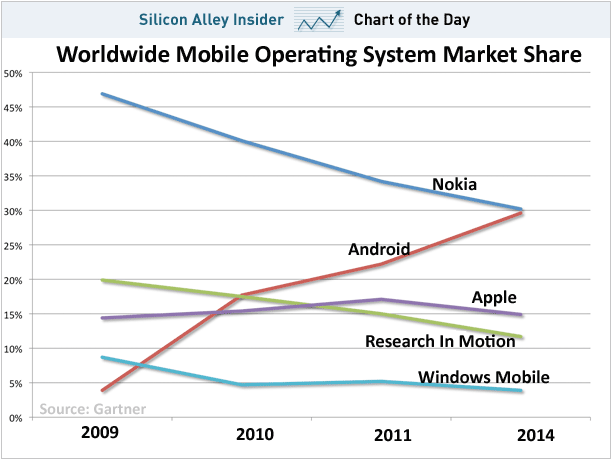

Why would a senior Microsoft exec want to head up Nokia?

Stephen Elop, a leading Microsoftie who was tipped to succeed Steve Ballmer, has left to become Nokia CEO. Maybe he knows something we don’t.

Chart from BusinessInsider. I found it on Jean-Louis Gassée’s startling picture of the mess that is Nokia today.

All predictions about the Net are wrong. (Except this one, of course)

This morning’s Observer column.

If I’ve learned one thing from watching the internet over two decades, it’s this: prediction is futile. The reason is laughably simple: the network’s architecture and lack of central control effectively make it a global surprise-generation machine. And since its inception, it has enabled disruptive innovation at a blistering pace.

This doesn’t stop people making predictions, though. In fact, ever since the web went mainstream in 1993 there has been a constant stream of what computer scientist John Seely Brown calls “endism” – assertions that some new technology presages the termination of some revered practice, not to mention the end of civilisation as we know it. The prediction that online news means the death of newspapers, for example, is almost as old as the web. More recent examples include Wired’s announcement of the imminent death of the web at the hands of iPhone apps and Nicholas Carr’s assertion that ubiquitous networking heralds the end of contemplative reading.

The problem with endism is that it’s intrinsically simplistic…

Life on screen, circa 2014

Cod video. The fun will come from watching it in 2014, when it will look a bit like this, I suppose:

Welcome to 1938

Sobering NYT column by Paul Krugman.

Here’s the situation: The U.S. economy has been crippled by a financial crisis. The president’s policies have limited the damage, but they were too cautious, and unemployment remains disastrously high. More action is clearly needed. Yet the public has soured on government activism, and seems poised to deal Democrats a severe defeat in the midterm elections.

The president in question is Franklin Delano Roosevelt; the year is 1938. Within a few years, of course, the Great Depression was over. But it’s both instructive and discouraging to look at the state of America circa 1938 — instructive because the nature of the recovery that followed refutes the arguments dominating today’s public debate, discouraging because it’s hard to see anything like the miracle of the 1940s happening again.

Now, we weren’t supposed to find ourselves replaying the late 1930s. President Obama’s economists promised not to repeat the mistakes of 1937, when F.D.R. pulled back fiscal stimulus too soon. But by making his program too small and too short-lived, Mr. Obama did just that: the stimulus raised growth while it lasted, but it made only a small dent in unemployment — and now it’s fading out…

Yep. And there’s no indication that Osborne & Co understand this.

Drawing the line between Twitter and Facebook

Christopher Caldwell had a typically thoughtful column in yesterday’s Financial Times, about the case of the Washington Post sportswriter, Mike Wise, and his Twitter experiments.

Mr Wise has built a reputation as one of America’s top basketball reporters. He has a radio show. He does interviews. And – fatefully – he stays in contact with his readers through Twitter. On Monday, Mr Wise “tweeted” three fake news stories. One concerned how long a suspension Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback Ben Roethlisberger would receive for alleged off-field misconduct. Mr Wise wrote: “Roethlisberger will get five games, I’m told.” The Miami Herald, The Baltimore Sun and NBC’s Pro Football Talk blog all cited the tweet.

Mr Wise then revealed that the story was a hoax – or, to put it charitably, a piece of freelance sociological fieldwork. Mr Wise had been critical of online “aggregators” who do not source their own stories or check facts independently. He explained, in an apology posted on Twitter, that he had been trying to “test the accuracy of social media reporting”.

The Post, however, didn’t see the joke and suspended him for a month. The paper’s argument was that his position as a senior writer in a major newspaper effectively meant that Mr Wise was not free to do what you or I might be free to do.

Mr Caldwell explores the complexities of the case. He points out that, in the first place, Wise’s “test” wasn’t exactly well-designed. What he wanted to test was the willingness of online aggregators to repeat allegations/stories without bothering to check them. But you might say that many people would think it reasonable to pass on without checking something they’ve got from a respected and knowledgeable source. In my case, for example, I’d be less concerned to check something from Nick Robinson’s blog than a rumour that I’d read in one of the UL political blogs. And I guess that if I were interested in American sports then I’d feel the same about Mr Wise.

But what of the Post‘s argument: that it has a right to demand certain kinds of behaviour from its journalists even in their private, or semi-private lives? It sounds a bit like the requirement that police officers should be circumspect in their off-duty behaviour. Here’s Caldwell again:

The real stakes of Mr Wise’s prank do not concern social journalism. They concern the broader matter of what belongs to institutions and what belongs to their members (or employees), and what each is entitled to demand of the other. Politics is always reminding us that this line is very hard to draw. When Newt Gingrich signed a multimillion-dollar book contract after the Republicans won the midterm elections of 1994, attention focused on Rupert Murdoch’s ownership of the publishing company that was paying him. An equally pertinent question, though, was whether Mr Gingrich was worth all that money because he was Newt Gingrich or because he was the presumptive Speaker of the House. If the latter, then he was arguably selling something that did not belong to him. The same goes for Barack Obama’s signing a multi-book contract after his election as Illinois senator in 2004.

Mr Wise appears to understand what he did wrong in just these terms. “I made a horrendous mistake,” he wrote, “using my Twitter account that identifies me as a Washington Post columnist.” Since it was a personal account, some might say that he hurt no one but himself. This is a line of thinking that the Post rightly moved to squelch. Mr Wise is thought of as a Washington Post columnist whether he identifies himself that way or not. This entitles the paper to make certain demands. The sports editor, Matthew Vita, circulated a copy of the Post’s new-media guidelines, which read, in part: “When you use social media, remember that you are representing The Washington Post, even if you are using your own account … All Washington Post journalists relinquish some of the personal privileges of private citizens. Post journalists must recognise that any content associated with them in an online social network is, for practical purposes, the equivalent of what appears beneath their bylines in the newspaper or on our website.”

But what if ‘social media’ become the dominant way in which social life is lived in the future? The Post probably wouldn’t feel entitled to complain if Mr Wise had tried his ruse in his local pub or golf club. It’s the fact that he did it in an arena that is ambiguously both public and private that causes the problem. So…

The internet and the new media are commonly described as a liberating, individualising force. In many respects, though, they are replacing informal relationships with surveilled ones. Mr Wise was wrong to put up his phoney tweets. The Post was within its rights to discipline him. But it is hard not to worry about the principles laid down in the process of doing so. The net result of the internet may be to invite the boss into what used to be the stronghold of one’s private life.

Come to think of it, though, this is a case where there’s an interesting difference between Facebook and Twitter. The latter is definitely a ‘public’ space — unless one explicitly protects one’s tweets, and I guess Mr Wise doesn’t. The Post might have had more trouble if he’d conducted his experiment in Facebook, where only his ‘friends’ would have seen it. Hmmm…

Anyway, this was a terrific column, by a terrific columnist.