An astonishingly thorough review by Anand Lai Shimpl and Brian Klug.

Kindle Fire blocks Google Apps

Well, well. This from Greg Knieriemen.

You cannot side-load or run any Google app that requires a login on the Kindle Fire. That means no Gmail, Google+, Google Voice I need to text my peeps or Google Docs.

Wonder what lies behind this. So much for the idea that the Fire is an Android device.

Why do good books sometimes fail to catch on?

As some readers may remember, I did a big Observer feature recently about Steven Pinker’s new book, which I think is a really significant and important work. So it was astonishing to learn yesterday from a well-informed source that UK sales of the book have been “very disappointing”.

This is really surprising given that: it’s a compelling and authoritative book; its author is a world-famous academic with a string of earlier best-sellers to his name; and the UK publishers (Penguin) organised a model pre-publication campaign for it which included, among other things, an RSA lecture given by him.

So why hasn’t The Better Angels of our Nature taken off in the UK? Two thoughts come to mind:

1. It’s too long. Or, rather, it’s 800-page bulk makes it look too intimidating — a bit like War and Peace or Ulysses, the kind of read that people think they could only tackle on a desert island.*

2. (Possibly allied to 1) The pre-publication publicity campaign had the counter-intuitive effect of making people think that they already knew enough about the book and so didn’t need to read it. This was because the ‘elevator pitch’ for it is easy to articulate: it is that, contrary to popular prejudice and conventional wisdom, violence in human societies has been steadily decreasing over a period of thousands of years. That is indeed a dramatic and compelling idea, but it’s not the only important thing to emerge from the book. First of all, there’s the care with which Pinker has marshalled the empirical evidence for his conclusion. And then there’s his intriguing, extensive and thoughtful examination of the possible causes for the decline in violence. So by inferring that the elevator pitch is all they need to know about the book, people are missing out on some really interesting stuff.

* Full disclosure: I’ve been putting off reading Anthony Briggs’s translation of War and Peace.

LATER: Two interesting comments. Jon Crowcroft (who is halfway through the book) thinks that “its not about the financial crisis so it isn’t a hot enough topic – i think it will be a slow burner – it is good, but it is too long and repetitive”. And Helle Porsdam asks, “Could another reason be that most people are not interested in reading all his terrible details about ways in which human beings have tortured and killed each other down through history – altogether too violent?”

Journalism and the uses of error

Years ago, in 2005, a Greek scientist published a fascinating article in PLoS Medicine in which he argued that most current published research ‘findings’ are false.

The probability that a research claim is true may depend on study power and bias, the number of other studies on the same question, and, importantly, the ratio of true to no relationships among the relationships probed in each scientific field. In this framework, a research finding is less likely to be true when the studies conducted in a field are smaller; when effect sizes are smaller; when there is a greater number and lesser preselection of tested relationships; where there is greater flexibility in designs, definitions, outcomes, and analytical modes; when there is greater financial and other interest and prejudice; and when more teams are involved in a scientific field in chase of statistical significance. Simulations show that for most study designs and settings, it is more likely for a research claim to be false than true. Moreover, for many current scientific fields, claimed research findings may often be simply accurate measures of the prevailing bias.

The interesting thing about this, as Alok Jha points out in a thoughtful Guardian piece, is that this comes as no surprise to professional scientists. Which only serves to highlight the intellectual and ideological chasm that divides the culture of journalism from the culture of scientific inquiry.

Delivering the Orwell lecture recently, Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger plainly stated what journalists should admit more often: that newspapers are full of errors. “It seems silly to pretend otherwise,” he said. “Journalism is an imperfect art – what Carl Bernstein likes to call the ‘best obtainable version of the truth’. And yet many newspapers do persist in pretending they are largely infallible.”

Yep. What’s truly weird is how reluctant journalists (and politicians) are to admit error. The minute a politician even hints that a rethink might be under way in government policy, hacks (most of whom have never run anything other than, occasionally, a bath) are jumping down his throat shouting “U Turn!” Outside the scientific mindset, writes Jha,

changes in direction are anathema to the world order. Journalists, politicians, business people and everyone else do not enjoy owning up to errors, because it chips away at their perceived authority. In politics, such change is called flip-flopping. Journalists hide behind the fig leaf of reader trust. (This has never made sense to me – why would your readers trust you more because you don’t acknowledge mistakes?)

Uncertainty, error and doubt are all confounding factors in whatever method you use to get at the truth. Acknowledging it and developing methods against it has been absorbed into scientific thinking – the most consistently successful method humans have developed to discover truth – and it seems churlish not to learn that lesson for the rest of life too.”

It’s possible that the Levenson Inquiry might recommend measures to compel journalists to admit to the margin of error in their reporting. But somehow I can’t see that chaning the prevailing mindset of the trade, once memorably expressed in the dictum: “Never apologise, and never explain”.

All of which brings to mind Keynes’s famous put-down of a journalist who complained that he had changed his position on monetary policy: “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”

The First Law of Internet services: no free lunch

This morning’s Observer column.

Physics has Newton’s first law (“Every body persists in its state of being at rest or of moving uniformly straight forward, except insofar as it is compelled to change its state by force impressed”). The equivalent for internet services is simpler, though just as general in its applicability: it says that there is no such thing as a free lunch.

The strange thing is that most users of Google, Facebook, Twitter and other “free” services seem to be only dimly aware of this law…

Hey Google, we want our screens back

Excellent post by Andy Hairgrove.

Google’s new designs WASTE vertical space. It is as if they designed their applications for a monitor/screen that is set on it's side (720 wide X 1280 high instead of 1280 wide X 720 high).

He’s right — as the illustrations in his post explain.

Joi Ito at the Judge Business School

Joi Ito, Director of the MIT Media Lab, gave a terrific talk on “Innovation in Open Networks” at the Judge Business School today.

Digital abundance

One of the points I often make in lectures is that economics has severe limitations as an analytical framework for looking at our new media ecosystem because it’s the study of the allocation of scarce resources, whereas what characterises the digital ecosystem is abundance. That sounds glib when I say it, but this installation by Erik Kessels — on show as part of an exhibition at Foam in Amsterdam — makes the point vividly. It features print-outs of all the images uploaded to Flickr in a single 24-hour period. There are several rooms like this…

.

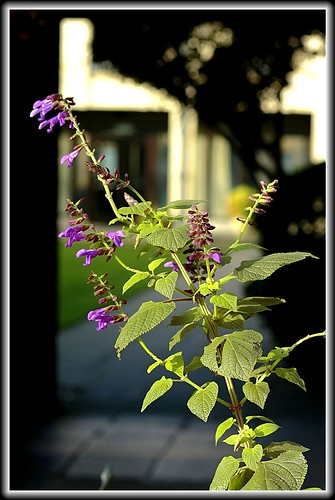

Light and shade

A real digital scholar

Back to the OU this afternoon (accompanied by my Arcadia Fellow, Helle Porsdam, who is doing a project on digital humanities) for the launch of Martin Weller’s new book, The Digital Scholar: How Technology Is Transforming Scholarly Practice. It’s a remarkably satisfying and rounded examination of three important and puzzling questions:

1. How is digital technology affecting scholarly practice?

2. How could it affect scholarly practice?

3. What are the implications for academia?

What’s great about Martin is that — unlike some academics — he doesn’t opine about this stuff from the sidelines: he lives and breathes networked scholarship. Thus he not only maintains a thoughtful and widely respected blog, but he campaigns energetically to have scholarly blogging recognised as a legitimate form of scholarly activity. He believes that academic work should be networked and open, and so refuses to do peer-reviewing for ‘closed’ journals. And in choosing a publisher for his new book, he went for Bloomsbury Academic, which publishes scholarly books under a Creative Commons licence. (Full disclosure: I’m on the Advisory Board of Bloomsbury Academic.) So you can buy the book in conventional print form. But you can also read it online for free.

I wish there were more academics like him.