Seen in a friend’s garden this afternoon.

Quote of the Day

“Don’t sleep with a drip. Phone a plumber.”

Seen on the back of a white van while sitting at traffic lights.

We love your work… now show us your workings

This morning’s Observer column.

The growth in computing power, networking and sensor technology now means that even routine scientific research requires practitioners to make sense of a torrent of data. Take, for example, what goes on in particle physics. Experiments in Cern’s Large Hadron Collider regularly produce 23 petabytes per second of data. Just to get that in context, a petabyte is a million gigabytes, which is the equivalent of 13.3 years of HDTV content. In molecular biology, a single DNA-sequencing machine can spew out 9,000 gigabytes of data annually, which a librarian friend of mine equates to 20 Libraries of Congress in a year.

In an increasing number of fields, research involves analysing these torrents of data, looking for patterns or unique events that may be significant. This kind of analysis lies way beyond the capacity of humans, so it has to be done by software, much of which has to be written by the researchers themselves. But when scientists in these fields come to publish their results, both the data and the programs on which they are based are generally hidden from view, which means that a fundamental principle of scientific research – that findings should be independently replicable – is being breached. If you can’t access the data and check the analytical software for bugs, how can you be sure that a particular result is valid?

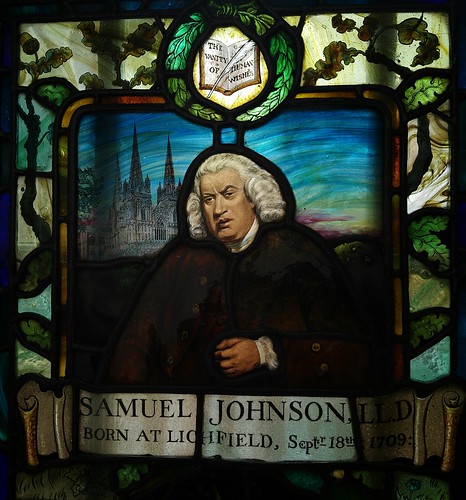

Dictionary Sam

The stained-glass portrait of Samuel Johnson in his house in Gough Square, just off Fleet Street, in London.

Flame, Stuxnet and cyberwar

From Good Morning Silicon Valley, citing the Washington Post.

There have been persistent whispers that the United States and Israel collaborated on the Stuxnet worm, which hit the computer systems of a nuclear plant in Iran a few years ago and was discovered in 2010. Earlier this month, spyware dubbed Flame was found on computers in Iran and elsewhere in the Middle East. Security experts have said Stuxnet and Flame have the same creators. Now the Washington Post reports, citing anonymous “Western officials,” that the U.S. and Israel were those creators; that Flame was created first; and that Flame and Stuxnet are part of a broader cyber-sabotage campaign against Iran. That campaign started under President George Bush and is continuing under President Barack Obama, according to a New York Times report earlier this month. (See Burning questions about Flame and cyberwar.) The Washington Post report describes Flame as “among the most sophisticated and subversive pieces of malware to be exposed to date” — a fake Microsoft software update that allows for a computer to be watched and controlled from afar.

On the surface…

… this has to be a spoof. Doesn’t it?

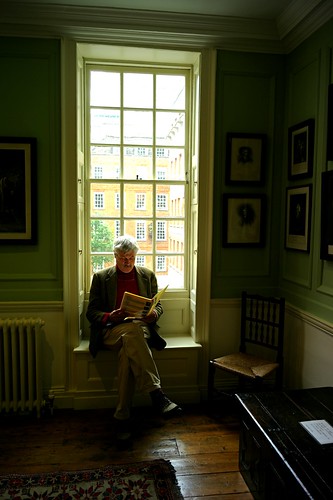

A reader in Dr Johnson’s house.

Believe it or Not!

The United Kingdom is one of America’s closest allies. The nations have together fought multiple wars, and remain closely tied commercially, politically, and militarily. Yet a 2006 National Geographic survey of young [American] adults found that only one in three could find the United Kingdom on a map.

From The Atlantic.

The same source claims that a 1999 Gallup poll revealed that 20 percent of Americans think that the sun revolves around the earth.

Innovation in an age of austerity

This lecture by Eben Moglen* of Columbia Law School is the most important thing I’ve seen in ages. It’s 90 minutes long (45 minutes talk + 45 minutes Q&A), so you need to make yourself a coffee and book some time out. But it’s worth it. And if you’ve really, really busy, then there’s a useful — but not comprehensive — set of notes by Stephen Bloch here.

Cory, who first alerted me to this, has ripped the audio so another way to access it is to put on an MP3 player and listen to it on the train or in the car.

Cory described the talk as “one of the most provocative, intelligent, outrageous and outraged pieces of technology criticism I’ve heard” and I agree. It’s also a useful antidote to the greatest evil of all — conventional wisdom.

*Footnote: For those who don’t know him, here’s a useful brief bio:

Eben Moglen has been battling to defend key digital rights for the last two decades. A lawyer by training, he helped Phil Zimmerman fight off the US government’s attack on the use of the Pretty Good Privacy encryption program in the early 1990s, in what became known as the Crypto Wars. That brought him to the attention of Richard Stallman, founder of the GNU project, and together they produced version 3 of the GNU GPL, finally released after 12 years’ work in 2006.

Today, he’s Professor of Law at Columbia Law School, Founding Director of the Software Freedom Law Center and the motive force behind the FreedomBox project to produce a distributed communication system, including social networking that is fully under the user’s control.