I’m not what you’d describe as a natural Facebooker. Sure I have a FB page and a bunch of ‘friends’ but I visit the site only rarely, and that’s mainly to find out what my kids or my friends’ kids are up to. Some Facebookers make the mistake of thinking that I’m an active user, but that’s because I’ve arranged for Twitter (of which I am an active user) to feed my tweets to FB where they appear as Updates.

All of which is by way of saying that my views on social networking are not based on deep personal experience and so should be taken with a pinch of salt. But, hey! this is a blog and blogs are places for unfinished thoughts, work-in-progress and the like. So here goes.

At the moment Facebook has two distinctive features. The first is a huge subscriber base — 900 million and counting. The second is a higher level of user engagement than any other service on the Web. Something like half of the users log in every day, and when logged in spend more time on the site than users of any other site. so the key question for anyone wanting to understand the Facebook phenomenon is: what’s driving them to do this?

I think I know the answer: it’s photographs — photographs that they or their friends have uploaded. Two reasons for thinking this: (1) the staggering statistics of how many photographs FB now hosts (100 billion according to some estimates), and the rate at which Facebookers upload them every day; and (2) personal observation of friends and family who are users of the site. Of course people also log into Facebook to read their friends’ status updates, newsfeeds/timelines, messages, wall-posts etc. But more than anything else they want to see who’s posted pics from last night, who’s been tagged in these images, and where (i.e. at which social event) the pictures were taken.

Hold that thought for a moment while we move to consider the speculation (now rampant) that Facebook is developing a smartphone. Henry Blodget thinks that this would be a crazy idea for seven different reasons, and I’m inclined to agree with him. (But then I would have said — probably did say — the same about Steve Jobs’s decision to enter the mobile phone market.)

Zuck & Co aren’t crazy — not in that way anyway — so let’s assume that they share Blodget’s view — that building a phone qua phone would be a daft idea. And yet everyone’s convinced that they are building something. So what is it?

Dave Winer, whom I revere, thinks it’s a camera. And not just any old camera, either, but what Dave calls a social camera. Here’s how he described it.

Here’s an idea that came to me while waiting for a train to Genova. I was standing on a platform, across a pair of tracks a man was taking a picture of something in my direction. I was in the picture, the camera seemed to be pointed at me.

I thought to yell my email address across the tracks asking him to send me a copy of the picture. (Assuming he spoke English and I could be heard over the din of the station.)

Then I thought my cell phone or camera could do that for me. It could be beaming my contact info. Then I had a better idea. What if his camera, as it was taking the picture, also broadcast the bits to every other camera in range. My camera, sitting in my napsack would detect a picture being broadcast, and would capture it. (Or my cell phone, or iPod.)

Wouldn’t this change tourism in a nice way? Now the pictures we bring home would include pictures of ourselves. Instead of bringing home just pictures that radiate from me, I’d bring home all pictures taken around me while I was traveling.

Of course if you don’t want to broadcast pictures you could turn the feature off. Same if you don’t want to receive them.

A standard is needed, but the first mover would set it, and there is an incentive to go first because it would be a viral feature. Once you had a Social Camera, you’d want other people to have one. And you’d tell them about it.

Dave wrote that in 2007, which is 35 Internet-years ago, and I remember thinking that it was a bit wacky when I first read it. But then I’m a serious (or at any rate an inveterate) photographer, and for me photographs are essentially private things — artefacts I create for my own satisfaction. Of course I am pleased if other people like them, but that’s just icing on the cake.

Over the years, though, my views changed. I bought an Eye-Fi card , which is basically just an SD card with onboard WiFi. Stick into your camera and it wirelessly transmits the images you take to a computer on the same Wi-Fi network. It’s fun (though a bit slow unless you keep the image size down) but can be useful at times — e.g. in event photography.

, which is basically just an SD card with onboard WiFi. Stick into your camera and it wirelessly transmits the images you take to a computer on the same Wi-Fi network. It’s fun (though a bit slow unless you keep the image size down) but can be useful at times — e.g. in event photography.

And then came the iPhone. The first two versions had crappy cameras, just like most other mobile phones. But from the 3S model onwards, the iPhone cameras improved to the point where they’re almost as good as the better point-and-shoot digital compacts. Given the First Law of Photography, which is that the best camera is the one you have with you, and given that most people always carry a phone whereas only hardcore snappers like me always carry a separate camera, it was only a matter of time before the market for compact cameras began to feel Christensen-type disruption . And so it has proved, to the point where the most popular ‘camera’ amongst Flickr users is now the iPhone 4.

. And so it has proved, to the point where the most popular ‘camera’ amongst Flickr users is now the iPhone 4.

Now start joining up these dots — as Dave Winer did in this blog post — and you can see the glimmer of an intriguing possibility. Consider: if we accept that (i) the Facebook geeks are smart, (ii) social photography is Facebook’s addictive glue, (iii) cameras have morphed into cameraphones and (iv) Facebook recently paid an apparently insane amount of money for Instagram, then maybe the device that Zuck & Co are incubating is actually a camera which has photo-sharing built in. And if it also happens to make phone calls and send texts well, that would be a bonus.

Neat, eh?

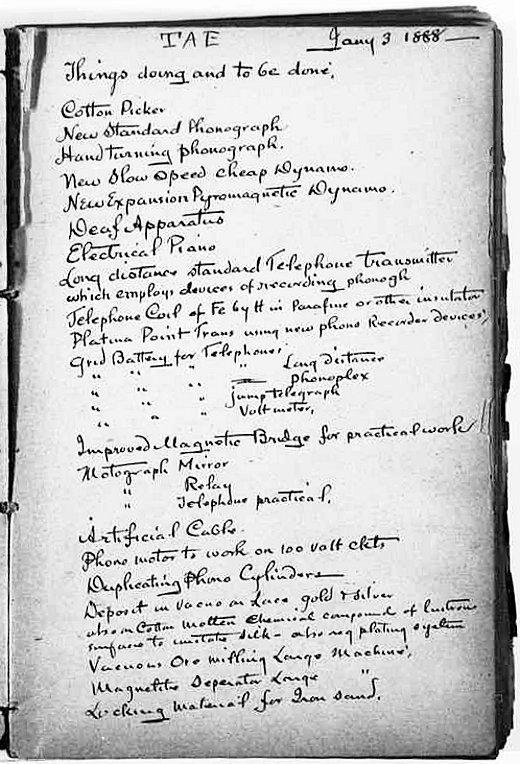

would have made of it. Edison breaks all the rules of his system.