Great talk by Martin Rees.

Writing home

Quote of the Day

“I don’t mind what anybody says about me, so long as it isn’t true”.

Truman Capote

Bill Stickers will be Prosecuted

The consolations of error

Lots of Observer readers have been writing to the Readers’ Editor (and emailing me directly) castigating me for claiming in my essay that Robert Capa’s D-Day Landing pictures were shot using a Leica camera. They maintain — as does Wikipedia — that he was using a Contax II rangefinder on the day, so I’m clearly in error on that point.

There is more disagreement about whether Capa’s famous Spanish Civil War photographs were shot with a Leica. There’s a photograph of him from the time carrying a movie camera with a stills camera in a leather case hanging round his neck. Not being an expert on camera cases, I don’t know whether it’s a Leica case or a Contax one. I guess Capa himself, a guy who covered five major wars, would have regarded this controversy as trivial. But it’s the kind of detail that we obsessives obsess about!

I wish I’d taken the trouble to check the D-Day assertion, but I guess because Capa had been one of the founder-members of Magnum I lazily assumed he had also been a Leica user. Myths endure because nobody checks. Mea culpa.

The same is true for the myths about Dorothy Parker, who is famous for being a world-class wisecracker. In an aside in the piece I claimed that she had reviewed Christopher Isherwood’s I Am A Camera with the crack “Me No Leica”. But, as many readers pointed out, the credit belongs elsewhere — with the theatre critic Walter Kerr. One of his most famous reviews was his three word summary of John Van Druten’s I Am A Camera in 1951: ‘Me no Leica.’

Parker has an enviable trove of wisecracks attributed to her, and she was an exceedingly funny (and exceedingly sad) lady. But in at least one other case she gets more credit than she deserves. When Robert Benchley came to her and said “Calvin Coolidge is dead”, she famously replied, “How could they tell?”, and this has gone down in history as an example of her wit. What’s not so well known, however, is that Benchley replied “He had an erection”, but this was deemed too scandalous for polite society at the time and so Parker’s punchline was the one that endured. Benchley’s widow allegedly went to her deathbed infuriated by the fact that her husband hadn’t got the credit he was due for that exchange.

Still, Eric Clapton hasn’t written in (yet) to say that he does sometimes remember to take the lens cap off his M8. And nobody from the Royal Household has been in touch to say that Her Majesty has, on occasion, forgotten to remove the cap on her M3.

Le Barroux

How to illustrate a point

I had a nice email from a colleague in India about my Observer column on the surveillance-based business model of the contemporary Web.

Excellent piece today John on surveillance being the revenue model of the Net.

When I read your piece, what was the banner ad on the Observer page? Jet Airways fares from Bombay to Delhi?

And what was one of the things I was looking for on the net earlier today…the price of air fares from Bombay to Delhi…including on Jet Airways.

Neat, eh?

The economics of Ebola

As someone who has written 50 newspaper columns a year for as long as I can remember, I know a really skilled practitioner of the columnist’s art when I see one. And one of the best is James Surowiecki of the New Yorker whose weekly ‘Financial Page’ is one of the wonders of the journalistic world. It’s not only unfailingly intriguing and informative, but it’s also clear and beautifully written.

Last week’s page on the economics of Ebola (and the economics of drug-discovery generally) is a typical gem. Surowiecki starts from the puzzle that while Ebola is one of the deadliest diseases known to mankind, nevertheless the pharmaceutical industry has developed no serious tools to combat it.

He then goes on to point out that this is only a puzzle to those who do not understand how the pharmaceutical industry works. “When pharmaceutical companies are deciding where to direct their R.& D. money”, he writes

very naturally assess the potential market or a drug candidate. That means that they have an incentive to target diseases that affect wealthier people (above all, people in the developed world), who can afford to pay a lot. They have an incentive to make drugs that many people will take. And they have an incentive to make drugs that people will take regularly for a long time – drugs like statins.

This system does a reasonable job of getting Westerners the drugs they want (albeit often at high prices). But it also leads to enormous underinvestment in certain kinds of diseases and certain categories of drugs. Diseases that mostly affect poor people in poor countries aren’t a research priority, because it is unlikely that those markets will ever provide a decent return. So diseases like malaria and tuberculosis, which together kill two million people a year, have received less attention from pharmaceutical companies than high cholesterol. Then, there’s what the World Health Organisation calls “neglected tropical diseases”, such as Chagas disease and dengue; they affect more than 1 billion people and kill as many as half a million a year. One study found that of the more than fifteen hundred drugs that came to market between 1975 and 2004 just ten were targeted at these maladies. And when a disease’s victims are both poor and not very numerous that’s a double whammy. On both scores, a drug for Ebola looks like a bad investment: so far, the disease has appeared only in poor countries and has affected a relatively small number of people.

This is, of course, bad news for people in poor countries. But Surowiecki goes on to point out that the business model of pharmaceutical companies poses serious risks for those of us who live in rich countries too. The case study he picks is the looming problem of diseases that have become resistant to our current arsenal of antibiotic drugs. The need for new, more powerful antibiotics grows with every passing day, but it’s not need that the industry – left to itself – will be able to address.

The trouble, again, is the business model. If a drug company did invent a powerful new antibiotics, we wouldn’t want it to be widely prescribed, because the goal would be to delay resistance. Public-health officials would – quite properly – try to limit sales of the drug as much as possible. Otherwise its efficacy would follow the same downward path as conventional antibiotics.

Which leaves us with a difficult public-policy problem: how can we get the drugs we will need without radically transforming the industry that makes them? The answer has to be some way of incentivising companies to do the research necessary to create substantial public-health benefits. And the only idea we seem to have for doing that at the moment is by going back to what the Board of Longitude did in the 18th century — getting governments to offer massive prizes for drugs that we may need but for which there is only a limited immediate market.

It’s a great column, worth reading in full.

The hitching post

The Leica phenomenon

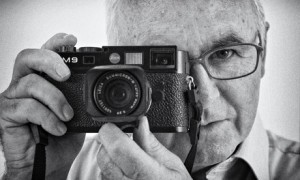

Photograph by Antonio Olmos for the Observer.

My Observer essay marking the centenary of the Leica camera.

I’m a photographer. No, let me rephrase that: I would like to be a photographer. In reality I’m merely an obsessive who takes lots of photographs in the hope that some day, just once, he will produce an image that is really, truly memorable. Like the images that Henri Cartier-Bresson captured, apparently effortlessly, in their thousands. Think, for example, of his famous picture of the guy leaping over a puddle; or the one of the two stout couples enjoying a picnic on the banks of the Marne; or his magical picture of a cheeky young boy carrying two bottles of red wine on the Rue Mouffetard in 1954. I like this last one particularly, because the lad in the photograph is about the same age as I was then and I often wonder if he’s still around, and what he looks like now.

You can think about this obsessiveness, this quest for the one perfect picture, as a kind of illness. If so, then I’ve had it for more than half a century. And I’m not the only sufferer…