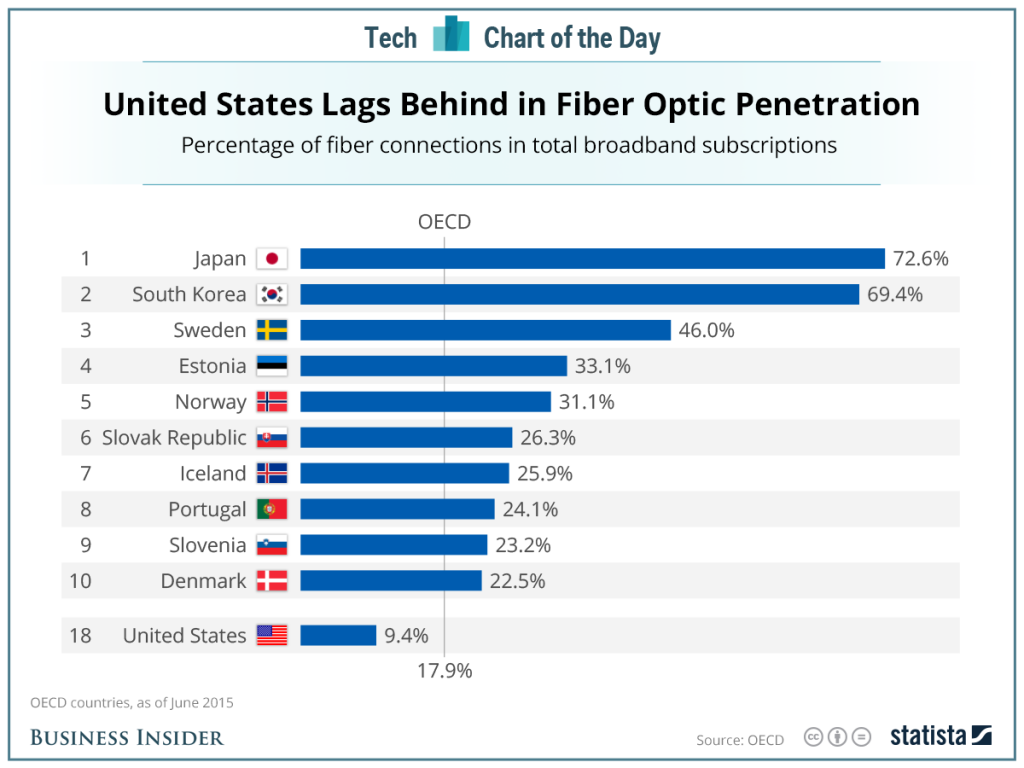

Anybody see where the UK went? Am I the only person in Britain with fibre to the home?

Brexit, 1997-style

This video was, I think, sent to every household in the UK in 1997. It will still resonate with some voters on June 23, I suspect.

Quote of the Day

“This case is like a crazy-hard law school exam hypothetical in which a professor gives students an unanswerable problem just to see how they do.”

Law Professor Orin Kerr, in a thoughtful and informative article on the dispute between Apple and the FBI over the San Bernardino killer’s iPhone 5.

Orion mission re-ignites moon landing conspiracy theories

Orion is NASA’s next-generation spacecraft, “built to take astronauts deeper into space than we’ve ever gone before”. The video was made to highlight the complexity of the design challenges, particularly the amount of protection needed to safeguard fragile equipment and astronauts as the craft hurtles through the Van Allen radiation belt. “Radiation like this could harm the guidance systems, on-board computers or other electronics on Orion,” says the personable narrator. “Shielding will be put to the test as the vehicle cuts through the waves of radiation… We must solve these challenges before we send people through this region of space.”

Aha! Cue moon landing conspiracy theorists. “If the moon missions were real”, says one then it seems the whole ‘punching through the Van Allen belt’ problem should have been solved over 40 years ago.”

Sadly, the problem wasn’t solved then. The Apollo astronauts were pushed through the belt on their way to the moon and back, on the basis that their exposure was brief and the amount of radiation they received was below the dose allowed by US law for workers in nuclear power stations.

Sigh. The “slaughter of a beautiful hypothesis by an ugly fact”, as TH Huxley used to say.

Lazy days

Killer Apps?

This morning’s Observer column:

“Guns don’t kill people,” is the standard refrain of the National Rifle Association every time there is a mass shooting atrocity in the US. “People kill people.” Er, yes, but they do it with guns. Firearms are old technology, though. What about updating the proposition from 1791 (when the second amendment to the US constitution, which protects the right to bear arms, was ratified) to our own time? How about this, for example: “algorithms kill people”?

Sounds a bit extreme? Well, in April 2014, at a symposium at Johns Hopkins University, General Michael Hayden, a former director of both the CIA and the NSA, said this: “We kill people based on metadata”. He then qualified that stark assertion by reassuring the audience that the US government doesn’t kill American citizens on the basis of their metadata. They only kill foreigners…

LATER In the column I discuss the decision-making process that must go on in the White House every Tuesday (when the kill-list for drone strikes is reportedly decided). This afternoon, I came on this account of the kind of conversation that goes on in Washington (possibly in the White House) when deciding whether to launch a strike:

“ARE you sure they’re there?” the decision maker asks. “They” are Qaeda operatives who have been planning attacks against the United States.

“Yes, sir,” the intelligence analyst replies, ticking off the human and electronic sources of information. “We’ve got good Humint. We’ve been tracking with streaming video. Sigint’s checking in now and confirming it’s them. They’re there.”

The decision maker asks if there are civilians nearby.

“The family is in the main building. The guys we want are in the big guesthouse here.”

“They’re not very far apart.”

“Far enough.”

“Anyone in that little building now?”

“Don’t know. Probably not. We haven’t seen anyone since the Pred got capture of the target. But A.Q. uses it when they pass through here, and they pass through here a lot.”

He asks the probability of killing the targets if they use a GBU-12, a powerful 500-pound, laser-guided bomb.

“These guys are sure dead,” comes the reply. “We think the family’s O.K.”

“You think they’re O.K.?”

“They should be.” But the analyst confesses it is impossible to be sure.

“What’s it look like with a couple of Hellfires?” the decision maker asks, referring to smaller weapons carrying 20-pound warheads.

“If we hit the right room in the guesthouse, we’ll get the all bad guys.” But the walls of the house could be thick. The family’s safe, but bad guys might survive.

“Use the Hellfires the way you said,” the decision maker says.

Then a pause.

“Tell me again about these guys.”

“Sir, big A.Q. operators. We’ve been trying to track them forever. They’re really careful. They’ve been hard to find. They’re the first team.”

Another pause. A long one.

“Use the GBU. And that small building they sometimes use as a dorm …”

“Yes, sir.”

“After the GBU hits, if military-age males come out …”

“Yes, sir?”

“Kill them.”

Less than an hour later he is briefed again. The two targets are dead. The civilians have fled the compound. All are alive.

Ok. You think I made that up. Well, I didn’t. The author is General Michael Hayden, who was director of the Central Intelligence Agency from 2006 to 2009. He is the author of the forthcoming book, Playing to the Edge: American Intelligence in the Age of Terror, from which (I’m guessing) the New York Times piece is taken.

The Wille E Coyote effect

Benedict Evans is at the huge annual mobile phone gabfest in Barcelona. On his way he wrote a very thoughtful blog post about the world before smartphones, and why Nokia and Blackberry didn’t see their demises coming.

Michael Mace wrote a great piece just at the point of collapse for Blackberry, looking into the problem of lagging indicators. The headline metrics tend to be the last ones to start slowing down, and that tends to happen only when it’s too late. So it can look as though you’re doing fine and that the people who said three years ago that there was a major strategic problem were wrong. You might call this the ‘Wille E Coyote effect’ – you’ve run off the cliff, but you’re not falling, and everything seems fine. But by the time you start falling, it’s too late.

That is, using metrics that point up and to the right to refute a suggestion there is a major strategic problem can be very satisfying, but unless you’re very careful, you could be winning the wrong argument. Switching metaphors, Nokia and Blackberry were skating to where the puck was going to be, and felt nice and fast and in control, while Apple and Google were melting the ice rink and switching the game to water-skiing.

I love that last metaphor.

In a way, it was another example of Clayton Christensen’s ‘innovator’s dilemma’. It’s the companies that are doing just fine that may be most endangered.

It’s a great blog post, worth reading in full. Also reminds us that mobile telephony was much more primitive in the US than it was in Europe (because of the GSM standard over here), and that Steve Jobs and co really hated their ‘feature’ phones as primitive devices. Evans sees something similar happening now with cars. It’s no accident, he thinks, that tech companies (Apple, Google) are working on cars. Techies hate cars in their current crude manifestations, whereas the folks who work in the automobile industry love them. Just as Nokia engineers once loved their hardware.

Economic populism: or one reason why Trump and Sanders are thriving

Nice New Yorker piece by James Surowiecki:

Both Trump and Sanders downplay the enormous economic benefits of globalization for American consumers of all incomes, and their proposed solutions are vague and could well be harmful if implemented. But their words resonate with many voters, because they articulate an important truth: free trade has created major winners and major losers in the U.S. economy, and the losers—mostly blue-collar workers—have received little or no help. Trade with China, in particular, has inflicted serious damage on American communities across the country, damage from which they have yet to recover. As the economists David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson have documented1, what they call the “China shock”—beginning in 1991 and lasting into this century—demolished manufacturing in much of the U.S. Workers in the affected communities had a hard time finding and keeping new jobs, and unemployment stayed high and wages low for at least a decade afterward.

Trade isn’t the only reason that blue-collar workers’ standard of living has declined; automation and weaker unions have also played a part. By focussing on trade, though, both candidates are acknowledging something important: what has happened to U.S. labor was not a natural disaster but, in part, the product of government policies designed to accelerate globalization and expose American workers to foreign competition. That admission is more than working-class Americans have got from most Presidential candidates.

-

The abstract for their NBER paper “The China Shock: Learning from Labor Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade” reads:

“China’s emergence as a great economic power has induced an epochal shift in patterns of world trade. Simultaneously, it has challenged much of the received empirical wisdom about how labor markets adjust to trade shocks. Alongside the heralded consumer benefits of expanded trade are substantial adjustment costs and distributional consequences. These impacts are most visible in the local labor markets in which the industries exposed to foreign competition are concentrated. Adjustment in local labor markets is remarkably slow, with wages and labor-force participation rates remaining depressed and unemployment rates remaining elevated for at least a full decade after the China trade shock commences. Exposed workers experience greater job churning and reduced lifetime income. At the national level, employment has fallen in U.S. industries more exposed to import competition, as expected, but offsetting employment gains in other industries have yet to materialize. Better understanding when and where trade is costly, and how and why it may be beneficial, are key items on the research agenda for trade and labor economists.” ↩

Umberto Eco RIP

Wonderful, sometimes exasperating, writer. I loved his newspaper columns and will always be grateful to him for How To Travel With A Salmon: and Other Essays. And for his wonderful 1994 essay on why the Mac is a Catholic machine, and the IBM PC a Protestant one. The NYT obit here

1984 photograph by Rob Bogaerts