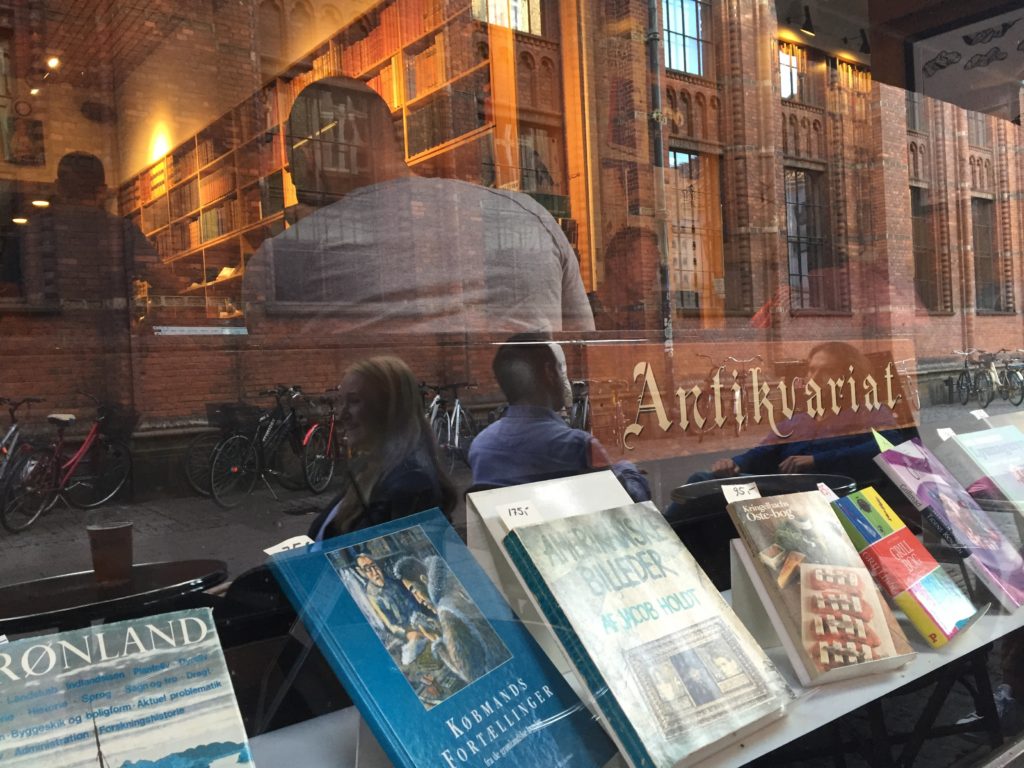

I’m writing this in one of my favourite haunts, the Paludan Cafe in Copenhagen, which is both a lovely cafe and an enchanting bookshop — the only bookshop in which I’ve seen university seminars conducted at 8am. It’s a beautiful Autumn day — sunny and mild — and I’ve walked through the city centre from a meeting in the University’s Law Faculty, marvelling as I went at how attractive this town is. It has a quiet spaciousness and a slower pace of life than London. And of course it has wonderful cafes.

In his book The Origins of Social Order the political theorist Francis Fukuyama argued that the messy, centuries-long groping of societies towards liberal democracy could be interpreted as the inchoate pursuit of a common (though unstated) goal: getting to Denmark. In other words, attempting to replicate the particular kind of liberal democracy that the Danes have been able to achieve: a prosperous, democratic, liberal, tolerant state in which, by international metrics, people are happier than they are anywhere else on the planet.

I never come here without thinking of that. This is indeed a seductively attractive polity. Copenhagen — which is the bit of the country I know best — is the most civilised city I know. And yet, even in this liberal democratic paradise, all is not well. The country’s parliament has just passed a law which permits the state to seize the assets of asylum-seekers to help pay for their stay while their claims are being assessed. The new law will also delay family reunions by increasing the waiting time from one to three years. 81 of the 109 MPs in the Parliament voted in support of the new legislation. Responding to public outrage, Parliament clarified that jewellery, including wedding rings, and other sentimental possessions would not be taken. But the UN and human rights organisations have condemned the legislation, saying it breaks international laws on refugees.

Yesterday, when I was walking to my hotel from the railway station, I crossed the square in front of the ornate City Hall, and noticed a large group of non-white people milling around. A guy was haranguing them with a megaphone, in a language I couldn’t understand. Some people were writing slogans on banners. Eventually, the group formed itself into a long file of marchers and set off downtown, shouting slogans (and holding up smartphones to get the obligatory video footage for subsequent uploading to Facebook). Finally, I found a banner that was written in English: “we want jobs, not charity” it read. These were refugees, and they were clearly unhappy with their experience of Mr Fukuyama’s nirvana.