Quote of the Day

”Never attribute to malice that which can adequately be explained by stupidity”.

- anon

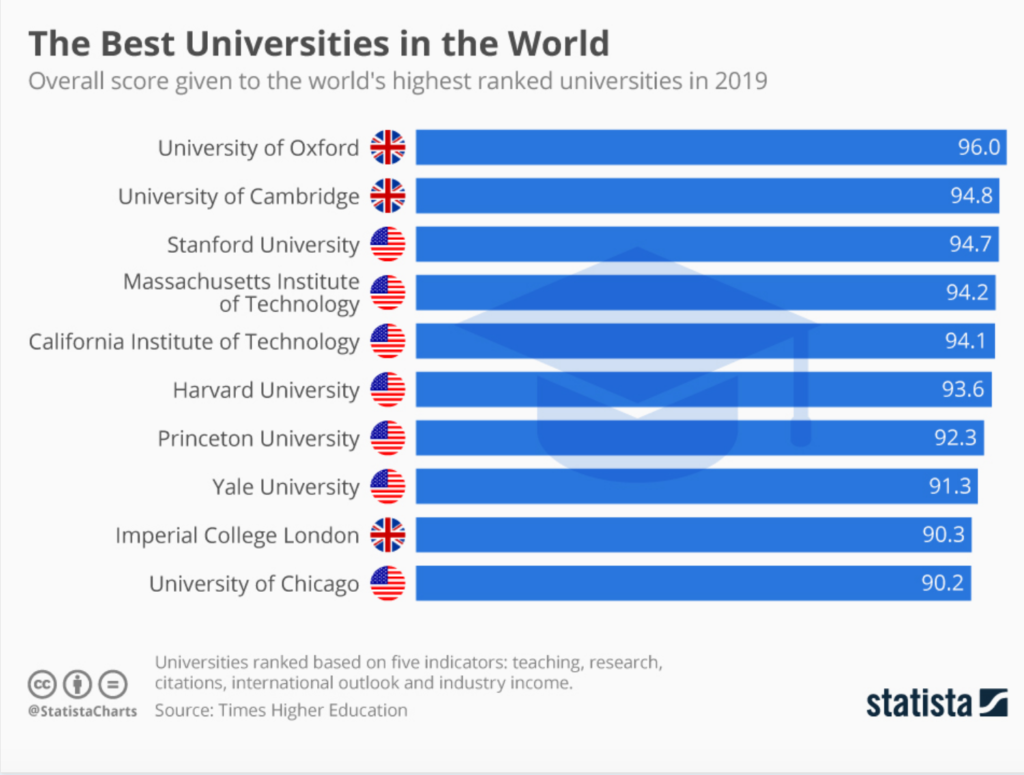

Best universities, 2019

Zero-days and the iPhone

This morning’s Observer column:

Whenever there’s something that some people value, there will be a marketplace for it. A few years ago, I spent a fascinating hour with a detective exploring the online marketplaces that exist in the so-called “dark web” (shorthand for the parts of the web you can only get to with a Tor browser and some useful addresses). The marketplaces we were interested in were ones in which stolen credit card details and other confidential data are traded.

What struck me most was the apparent normality of it all. It’s basically eBay for crooks. There are sellers offering goods (ranges of stolen card details, Facebook, Gmail and other logins etc) and punters interested in purchasing same. Different categories of these stolen goods are more or less expensive. (The most expensive logins, as I remember it, were for PayPal). But the funniest thing of all was that some of the marketplaces operated a “reputation” system, just like eBay’s. Some vendors had 90%-plus ratings for reliability etc. Some purchasers likewise. Others were less highly regarded. So, one reflected, there really is honour among thieves.

But it’s not just credit cards and logins that are valuable in this underworld…

Quote of the Day

“It’s absurd to believe that you can become world leader in ethical AI before becoming world leader in AI first”

— Ulrike Franke, policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

Camera Obscura

Brexit — what next?

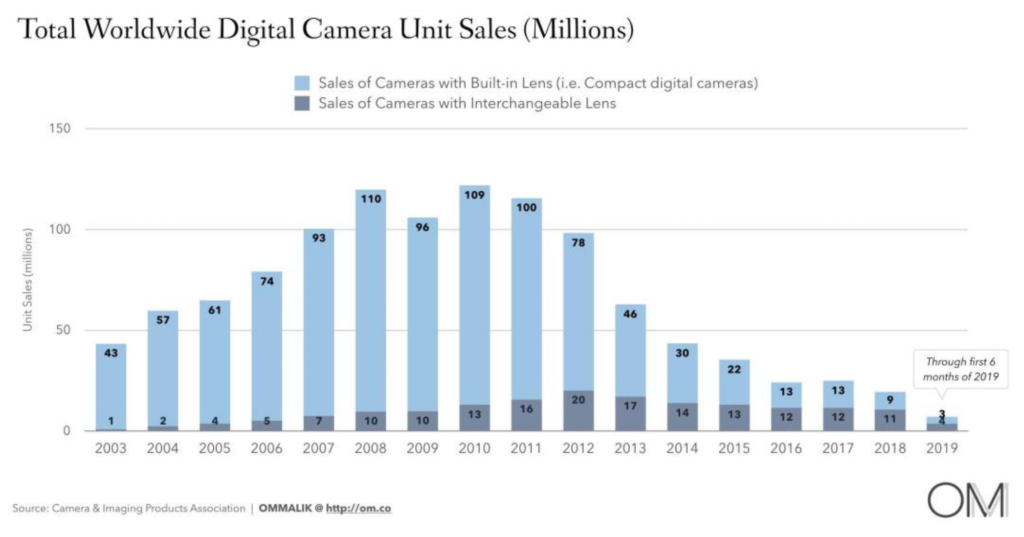

Traditional cameras are going the way of servers

This is from Om Malik’s blog:

Camera sales are continuing to falling off a cliff. The latest data from the Camera & Imaging Products Association (CIPA) shows them in a swoon befitting a Bollywood roadside Romeo. All four big camera brands — Sony, Fuji, Canon, and Nikon — are reposting rapid declines. And it is not just the point and shoot cameras whose sales are collapsing. We also see sales of higher-end DSLR cameras stall. And — wait for it — even mirrorless cameras, which were supposed to be a panacea for all that ails the camera business, are heading south.

Of course, by aggressively introducing newer and newer cameras with marginal improvements, companies like Fuji and Sony are finding that they might have created a headache. There is now a substantial aftermarket for casual photographers looking to save money on the companies’ generation-old products. Even those who can afford to buy the big 60-100 megapixel cameras are pausing. After all, doing so also involves buying a beefier computer. (Hello Mac Pro, cheese grater edition!)

I have seen this movie play out before — but in a different market…

Astute and, I think, accurate. Worth reading in full. The cultural implications of the shift of photography to smartphones are still not understood — though Om has been doing his best. See, for example, his 2016 New Yorker essay “In the future we will photograph everything and look at nothing”.

Pizza Romana

Quote of the Day

It is widely known that Mr. Johnson wants a “people versus politicians” election. Perhaps it is time for the opposition to push for “the country versus Boris Johnson.”

Today’s New York Times