Acrobatics in Venice

Quote

“Only in the most unusual cases is it useful to determine whether a book is good or bad. It is usually both”

- Robert Musil

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

The blackbird (hornpipe) ; The chorus (reel) | Padraig McGovern & Peter Carberry

Long read of the Day

Alison Gopnik: the Grandmother Hypothesis

This is an utterly fascinating essay by one of the most insightful thinkers about children and human development I’ve encountered. Here’s how it begins:

Human beings need special care while we are young and when we become old. The 2020 pandemic has made this vivid: millions of people across the world have taken care of children at home, and millions more have tried to care for grandparents, even when they couldn’t be physically close to them. COVID-19 has reminded us how much we need to take care of the young and the old. But it’s also reminded us how much we care for and about them, and how important the relations between the generations are. I have missed restaurants and theatres and haircuts, but I would easily give them all up to be able to hug my grandchildren without fear. And there is something remarkably moving about the way that young people transformed their lives to protect older ones.

But this raises a puzzling scientific paradox. We know that biological creatures are shaped by the forces of evolution, which selects organisms based on their fitness – that is, their ability to survive and reproduce in a particular environment. So why has it allowed us to be so vulnerable and helpless for long stretches of our lives? Why do the strong, able humans in their prime of life put so much time and energy into caring for those who are not yet, or no longer, so productive? New research argues that those vulnerabilities are intimately related to some of our greatest human strengths – our capacities for learning, cooperation and culture…

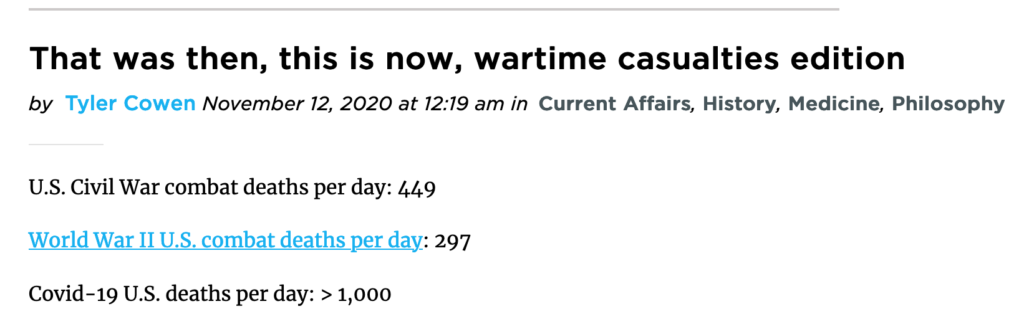

The Economist on Covid vaccines: “The technology of hope”

This is the best and most informative piece I’ve read on the reality, problems and potential of Covid vaccines.

DELIVERANCE, WHEN it arrives, will come in a small glass vial. First there will be a cool sensation on the upper arm as an alcohol wipe is rubbed across the skin. Then there will be a sharp prick from a needle. Twenty-one days later, the same again. As the nurse drops the used syringe into the bin with a clatter, it will be hard not to wonder how something so small can solve a problem so large.

On November 9th Pfizer and BioNTech, two firms working as partners on a vaccine against covid-19, announced something extraordinary about the first 94 people on their trial to develop symptoms of the disease. At least 86 of them—more than nine out of ten—had been given the placebo, not the vaccine. A bare handful of those vaccinated fell ill. The vaccine appeared to be more than 90% effective.

Within a few weeks the firms could have the data needed to apply for emergency authorisation to put the vaccine to use. The British and American governments have said that vaccinations could start in December. The countries of the EU have also been told it will be distributed quickly…

Yes, but that’s just the start of it. Worth reading in full.

Scott Galloway on Corona Corps

Scott Galloway is one of my favourite commentators on the tech industry. But he’s also good on politics — as well as being very perceptive (and critical) on how universities in the US are swindling students during the pandemic. He has an intriguing blog post this week in which he advances an idea of how to marshal the students who are currently being cheated out of an education while also doing what needs to be done to bring the pandemic. It’s an idea borrowed from the Peace Corps of the 1960s.

The equation for flattening the curve is simple: Testing x Tracing x Isolation = Flattening. On the whole, unless you are a Floridian, Americans have answered the call to take up arms (distancing) against the enemy. Testing is still a sh*tshow, but private-sector leaders (Bezos, Bloomberg) are trying to fill the void of federal incompetence. The missing link may be tracing. We currently have approximately 2,500 tracers who focus mostly on STDs and food-borne illnesses. The amount of time, hours really, between someone coming into contact with the virus and being isolated is paramount. We need 100,000 to 300,000 tracers.

As he puts it, “An Army Stands Ready”. Kids shouldn’t be going to college until the virus has been brought under control. They should all have a gap year — but one spent doing something that is socially useful: working on testing and tracing in the Corona Corps. Just like the Peace Corps back in the day.

This fall, 4 million kids are supposed to show up on campuses around the nation. I have 280 kids registered for my fall Brand Strategy class. I don’t believe it’s going to happen. The thought of 280 kids sitting elbow to elbow in a classroom presents our trustees with a challenging scenario.

Gap years should be the norm, not the exception. An increasingly ugly secret of campus life is that a mix of helicopter parenting and social media has rendered many 18-year-olds unfit for college. Parents drop them off at school, where university administrators have become mental health counselors. The structure of the Corona Corps would give kids (and let’s be honest, they are still kids) a chance to marinate and mature. The data supports this. 90% of kids who defer and take a gap year return to college and are more likely to graduate, with better grades. The Corps should be an option for non-college-bound youth as well.

Other, hopefully interesting, links

-

Joe Biden went out cycling today. A man after my own heart. Link

-

New device puts music in your head — no headphones required. Yeah, I know, I’m a gadget freak, but this is interesting. Link. There’s a video aimed at sceptics (I think).

-

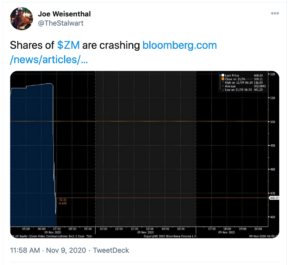

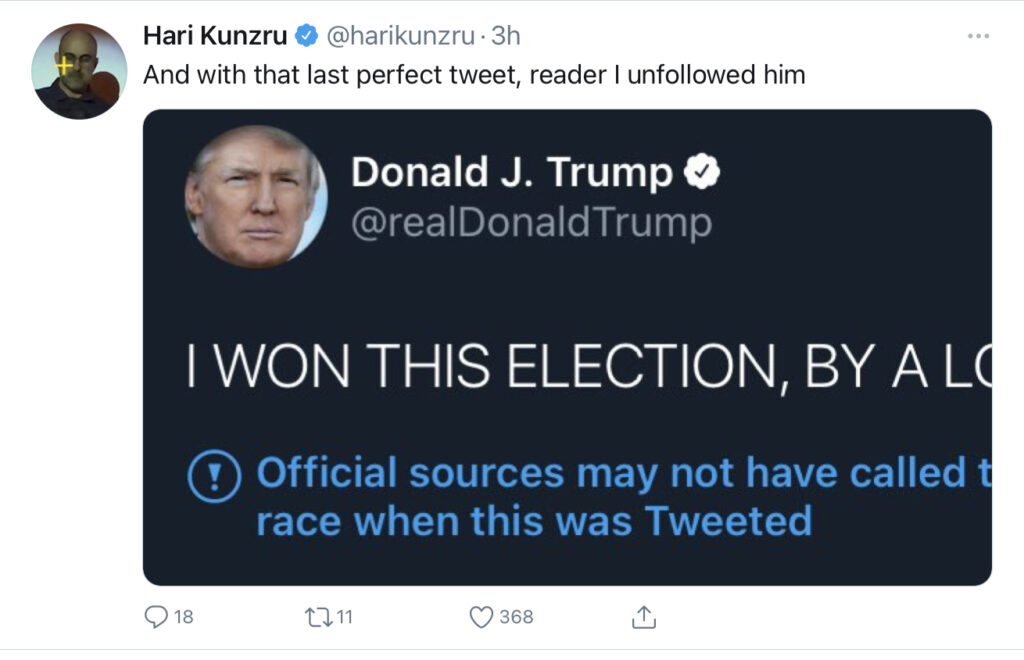

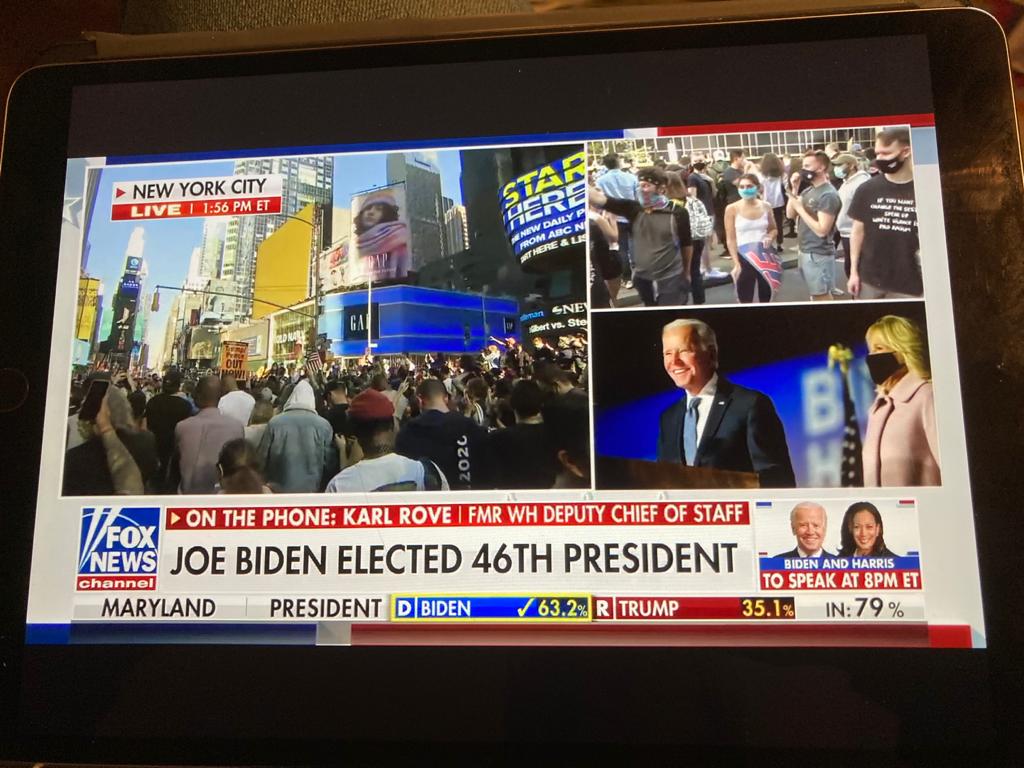

China congratulates Joe Biden on being elected President. Interesting: they must know something the Republicans don’t. Link.

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if your decide that your inbox is full enough already!