You don’t have to be an economist to worry about rising inequality (in fact it’s probably better if you’re not an economist, because most of them don’t seem to be much bothered by it). But on the list of existential problems that we apparently cannot solve, inequality ranks even above global warming. And what is really infuriating is the persistent cant of governments everywhere about it. Inequality and social deprivation are, we are told, regrettable and inescapable difficulties that mar an otherwise excellent system, like the exhaust fumes from a 3-litre smooth-running, straight-six BMW engine. They are, in other words, bugs.

No they’re not: they’re features. They are what the capitalist system produces in the course of its normal operation. And inequality is getting worse. In fact, in some countries it’s reached alarming levels — alarming because it frays the social fabric that makes civilised life possible.

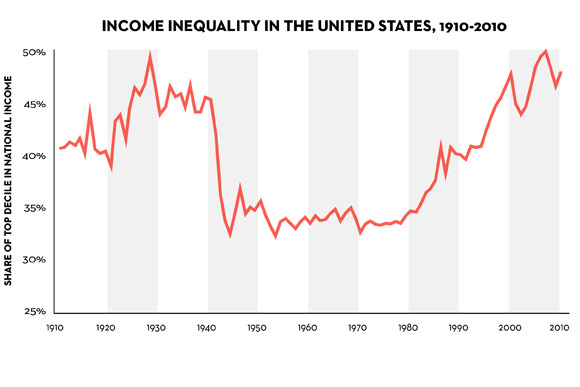

But somehow the debate about inequality seems to have stalled. Instead people obsess about the ‘growth’ needed to pull us out of ‘austerity’. All of which makes the publication of a new book by a young French economist, Thomas Piketty, so interesting and timely. It’s entitled Capital in the Twenty-First Century and it examines the dynamics that drive the accumulation and distribution of capital and how those forces have played out since the 18th century. (See the graph above, which is based on one of Piketty’s diagrams.) In his book, Piketty presents and analyzes data painstakingly assembled from twenty countries and going as far back as the eighteenth century. He shows shows that while modern economic growth and the diffusion of knowledge have allowed us to avoid inequalities on the apocalyptic scale predicted by Marx, nevertheless the deep structures of capital and inequality haven’t changed as much as the decades after World War II led us to believe. Piketty shows that inherited wealth is rapidly re-assuming its traditional role as the primary source of economic power. And the main driver of inequality — which is the fact that returns on capital tend to exceed the rate of economic growth — today threatens to generate the extreme inequalities that stir social and political discontent and undermine democracies.

John Cassidy has a terrific long piece about Piketty’s book in this week’s New Yorker. The Berkeley economist and blogger, Brad de Long, has also compiled a useful compendium of reviews of the book that have appeared so far. For me, the really significant aspect of Piketty’s work is that he shows how economics is inextricably bound up with politics — an idea that is anathema to an economics discipline that until recently was busily trying to emulate physics (without bothering to do what physicists have to do, namely to check their work against physical reality). Economics used to be called “political economy”, which was a good description of what the discipline ought to be, even today. Especially today.

The implication is that if we want to do something about inequality, then we have to take political action to bring the rate of return on capital into sync with wages and earned income. This happened briefly in the 20th century because two world wars and a depression destroyed a lot of capital. But the old dynamic has reasserted itself, with a vengeance, and inequality is set to rise to 19th century levels or worse if we don’t do something about it. The obvious way to do it is via a serious, global taxation regime on wealth. The system won’t fix itself, because it can’t. Inequality is one of its products, remember.