It’s difficult to know where to start with the Wikileaks stash of documents reported on today by the Guardian, NYT and Der Spiegel.

1. Maybe we should begin with what we can learn from the continued existence of Wikileaks, despite all the best efforts of dozens of powerful companies and governments to exterminate it. There’s a thoughtlessness about journalistic acceptance of the proposition that Wikileaks confirms the truth of John Gilmore’s celebrated aphorism that “the Internet interprets censorship as damage and routes around it”. The implication is that all one has to do is publish something on a website somewhere and then the truth is out. Sadly, that’s often not the case: one of the hard lessons we libertarians have learned over the last two decades is that it’s all too easy to censor the Web: all you need is a take-down letter from a lawyer in most cases, and nine out of ten ISPs or hosting services will take down a site, no questions asked. (That’s been the chilling effect of the ‘Demon Internet’ case.)

The indestructibility of Wikileaks, despite the best efforts of the cream of the world’s corporate and national security goons to muzzle it, stems from the amazing commitment, determination and technical know-how of the group of activists behind it. To get a feeling for what’s involved, it’s worth having a look at Raffi Khatchadourian’s remarkable New Yorker profile of Julian Assange, the prime mover behind the service. Most of the technical detail behind Wikileaks’s operations are hidden, but here’s what Khatchadourian found out:

As it now functions, the Web site is primarily hosted on a Swedish Internet service provider called PRQ.se, which was created to withstand both legal pressure and cyber attacks, and which fiercely preserves the anonymity of its clients. Submissions are routed first through PRQ, then to a WikiLeaks server in Belgium, and then on to “another country that has some beneficial laws,” Assange told me, where they are removed at “end-point machines” and stored elsewhere. These machines are maintained by exceptionally secretive engineers, the high priesthood of WikiLeaks. One of them, who would speak only by encrypted chat, told me that Assange and the other public members of WikiLeaks “do not have access to certain parts of the system as a measure to protect them and us.” The entire pipeline, along with the submissions moving through it, is encrypted, and the traffic is kept anonymous by means of a modified version of the Tor network, which sends Internet traffic through “virtual tunnels” that are extremely private. Moreover, at any given time WikiLeaks computers are feeding hundreds of thousands of fake submissions through these tunnels, obscuring the real documents. Assange told me that there are still vulnerabilities, but “this is vastly more secure than any banking network.”

And the moral of this? Using the Internet to further ‘disruptive transparency’ takes a lot more than simply posting stuff to a website.

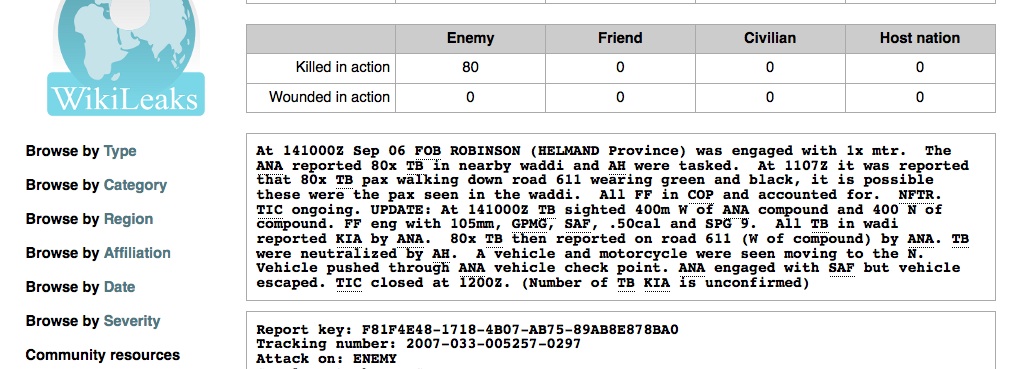

2. Then there’s the question of what the Wikileaks stash tells us about the war. Amy Davidson went digging and pulled up this interesting snippet. Dated November 22nd, 2009, it was submitted by a unit called Task Force Pegasus and describes how a US convoy was stopped on a road in southern Afghanistan at an illegal checkpoint manned by what appeared to be a hundred insurgents, “middle-age males with approx 75 x AK-47’s and 15 x PKM’s.”

These weren’t “insurgents” at all, at least not in the die-hard jihadi sense that the American public might understand the term. The gunmen were quite willing to let the convoy through, if the soldiers just forked over a two or three thousand dollar bribe; and they were in the pay of a local warlord, Matiullah Khan, who was himself in the pay, ultimately, of the American public. According to a Times report this June (six months after the incident with Task Force Pegasus), Matiullah earns millions of dollars from NATO, supposedly to keep that road clear for convoys and help with American special-forces missions. Matiullah is also suspected of earning money “facilitating the movement of drugs along the highway.” (He denied it.)

That is good to know, says Ms Davidson, and she’s right.

The Obama Administration has already expressed dismay at WikiLeaks for publicizing the documents, but a leak that informs us that our tax dollars may be being put to use as seed money for a protection racket associated with a narcotics-trafficking enterprise is a good leak to have. And the checkpoint incident is, again, only one report, from one day. It will take some time to go through everything WikiLeaks has to offer—the documents cover the period from January, 2004 to December, 2009—but it is well worth it, especially since the war in Afghanistan is not winding down, but ramping up.

3. Finally, there’s the grotesque absurdity of the war itself. To someone of my age who lived through the Vietnam era, the parallels are very striking. What really takes my breath away now, though, is the intellectual and evidential poverty of the justifications for it — especially the threadbare mantra of the Labour and Coalition administrations that British soldiers are dying in Helmand in order to protect the good citizens of Bradford. In that context, George Packer had a good piece in the New Yorker on July 5, which said, in part:

With allies like Canada and Holland heading for the exits, American troops are dying in larger numbers than at any point of the war—on bad days, ten or more. The number of Afghan civilian deaths remains high, despite the tightened constraints of McChrystal’s rules of engagement. The military key to counterinsurgency is protection of the population, but the difficulty in securing Marja and the delay of a promised campaign in Kandahar suggest that the majority of Afghan Pashtuns no longer want to be protected by foreign forces. The political goal of counterinsurgency is to strengthen the tie between civilians and their government, but the Afghan state is a shell hollowed out by corruption, and at its center is the erratic figure of President Karzai. Since last fall, when he stole reëlection, Karzai has accused Western governments and media of trying to bring him down, fired the two most competent members of his cabinet, and reportedly threatened to join the Taliban and voiced a suspicion that the Americans were behind an attack on a peace conference he recently hosted in Kabul. In the face of his wild performance, the current American approach is to tiptoe around him, as if he would start behaving better if he could just be settled down. Meanwhile, aid efforts are in a bind: working with the government nourishes corruption; circumventing it further undermines its legitimacy.

The Wikileaks stash shows how badly “protection of the population” is going. So,

Obama is trapped—not by his generals but by the war. It takes great political courage to face such a situation honestly, but if in a year’s time the war looks much the way it does now, or worse, Obama will have to force the public to deal with the likely reality: Americans leaving, however slowly; Afghanistan slipping into ethnic civil war, with many more Afghan deaths; Pakistan backing the Pashtun side; Al Qaeda seizing the chance to expand its safe haven. These consequences would require a dramatically different U.S. strategy, and a wise Administration would unify itself around the need to think one through before next summer.

Maybe there was a chance after 9/11 of doing what no foreign power in history had ever managed to do — create a semblance of a unified nation-state from the chaotic patchwork of fiefdoms that is Afghanistan. But that was blown by the Bush administration’s obsession with Iraq, which drained away the colossal effort that would have been needed to re-model Afghanistan. So now there’s no option except to accept the inevitable. The game’s over, and the West blew it. And, as far as I can see, there’s no Plan B.