Nighttime

Pembroke College, Cambridge on a chilly January night. I arrived early, and instead of waiting in the cold for my host decided to sit in the chapel where an orphan scholar was practising. I’d forgotten how beautifully spare the building is. And then I remembered that it was designed by Christopher Wren.

Quote of the Day

”I went from adolescence to senility, trying to bypass maturity.

- Tom Lehrer

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Bruce Springsteen | Shenandoah (The Seeger Sessions)

Long Read of the Day

How to Raise Your Artificial Intelligence

A conversation with Alison Gopnik and Melanie Mitchell.

This is an absolutely riveting read. A perceptive and intelligent interviewer in conversation with two genuine luminaries. Here’s a sample — from an interaction on the so-called ‘alignment problem’ in AI:

How important for this next generation of robots and AI systems is incorporating social traits such as emotions and morality?

Mitchell: Intelligence includes the ability to use tools to augment your intelligence, and for us, the main tool we use is other people. We have to have a model of other people in our heads and be able to, from very little evidence, figure out what those people are likely to do, just like we would for physical objects in the real world. This theory of mind and ability to reason about other people is going to be essential for getting robots to work both with humans and with other intelligent robots.

Gopnik: Some things that seem very intuitive and emotional, like love or caring for children, are really important parts of our intelligence. Take the famous alignment problem in computer science: How do you make sure that AI has the same goals we do? Humans have had that problem since we evolved, right? We need to get a new generation of humans to have the right kinds of goals. And we know that other humans are going to be in different environments. The niche in which we evolved was a niche where everything was changing. What do you do when you know that the environment is going to change but you want to have other members of your species that are reasonably well aligned? Caregiving is one of the things that we do to make that happen. Every time we raise a new generation of children, we’re faced with this difficulty of here are these intelligences, they’re new, they’re different, they’re in a different environment, what can we do to make sure that they have the right kinds of goals? Caregiving might actually be a really powerful metaphor for thinking about our relationship with AIs as they develop…

Do read it. It sheds different lights on things that baffle us at the moment.

Books, etc.

The social life of ideas

Diane Coyle has been re-reading Louis Menand’s book on the intellectual ferment in post-civil-war America. She has some characteristically thoughtful reflections on the experience.

I re-read a book I first read in 2002 when the first UK paperback was published, Louis Menand’s magnificent The Metaphysical Club: A story of ideas in America. It takes a sweeping view of the reshaping of the climate of ideas in the US after the Civil War, when pre-war traditions were replaced thanks to a combination of influences: the professionalisation of intellectual life in universities, the impact of scientific discovery particularly Darwin, and indeed the consequences of the Union victory. By the late 19th century the broadly defined pragmatist perspective that lasted until the 1960s – including an accommodation among White Americans over the status of African-Americans – was in place. The story is told though the intertwined histories of William James, Charles Peirce, Oliver Wendell Holmes and John Dewey.

The book lived up to my memory of its excellence, although newly poignant as the idea of an intellectual life among the new US ruling class seems increasingly like a contradiction in terms…

Yep. My friend Sean French and I have a rule: whenever Menand has an essay in the New Yorker, it’s the first thing we turn to.

Diane’s post reminded of something Julian Barnes wrote somewhere (I cited it last September but didn’t cite the reference):

“If reading is one of the pleasures – and necessities – of youth, rereading is one of the pleasures – and necessities – of age. You know more, you understand both life and literature better, and you have the additional interest of checking your younger self against your older self.”

My commonplace booklet

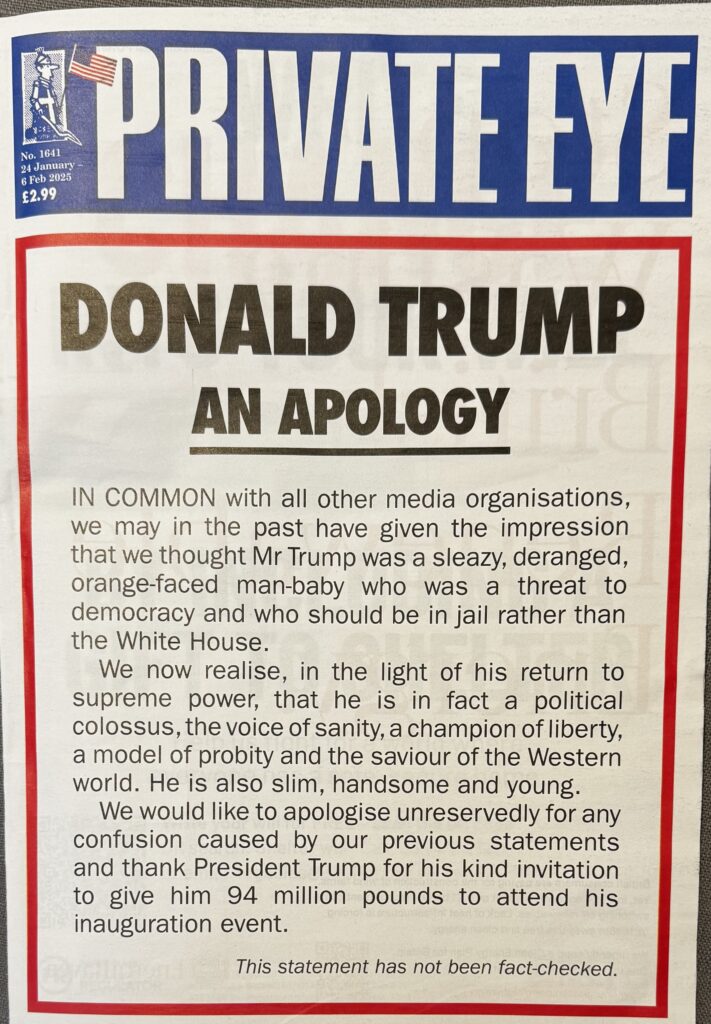

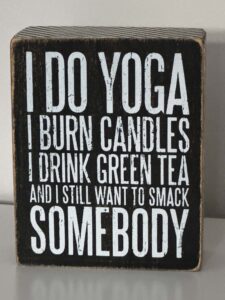

This is from 1930. Plus ca change!

Linkblog

Something I noticed, while drinking from the Internet firehose.

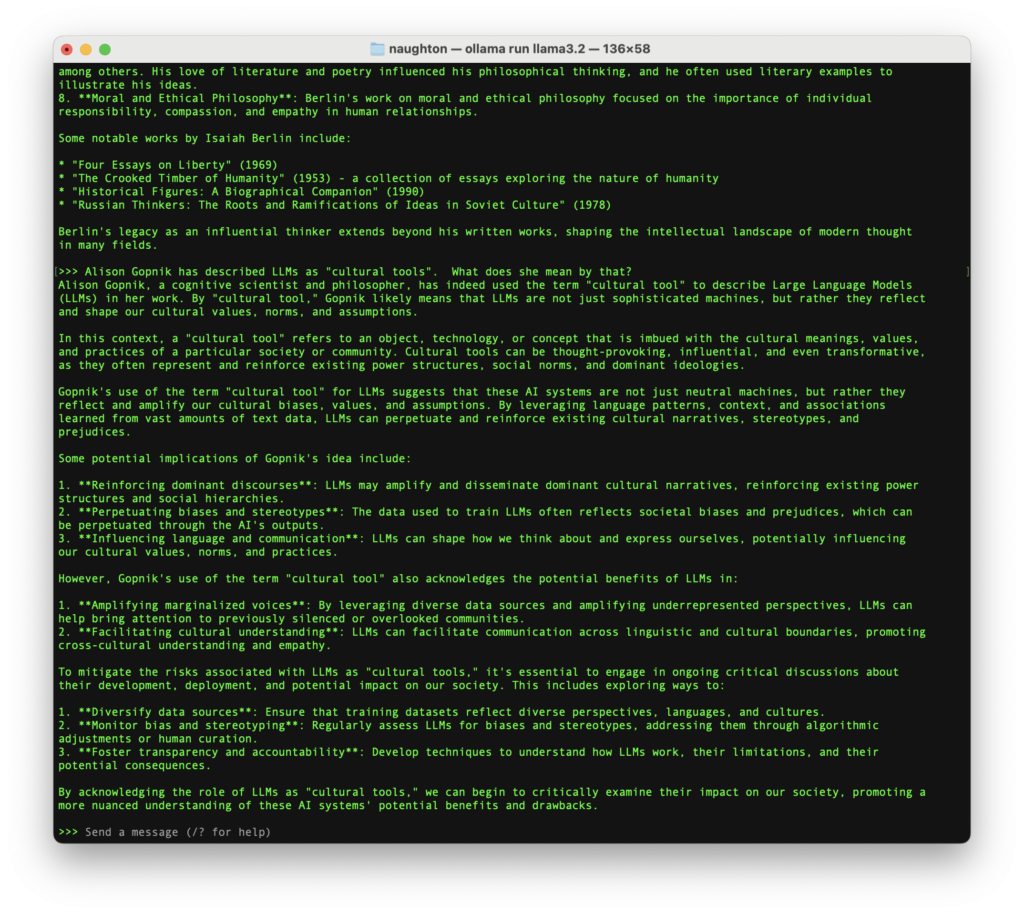

I’ve been running Deepseek R1, the Chinese LLM which is causing quite a stir, on my laptop. It’s intriguing for all kinds of reasons (see my column in next Sunday’s Observer if you’re interested), but I’ve noticed that other people have been stretching it a bit and finding that it’s a lot less buttoned-up than its Silicon Valley counterparts. Which is odd, when you think about it, given that the Chinese constitution doesn’t have a First Amendment.

Here’s an example from a user who asked the model to write about the so-called “Alignment” problem in AI in a ‘spicy’ style.

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 6am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!