Unplanned obsolescence

A lovingly cared-for Harley seen in a French village the other day. En passant, isn’t it amazing how humans tamed the internal combustion engine so that we could ride around comfortably while being propelled by a controlled series of explosions?

Quote of the Day

“I may have my faults, but being wrong ain’t one of them”

- Jimmy Hoffa

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Louis Armstrong with Dave Brubeck | Summer Song

Long Read of the Day

“Bits of the Mind’s String”

Lovely essay by Julian Simpson on what you can learn about yourself from keeping a notebook.

I know where I was when I wrote that note because the time and place is scrawled at the top of the page. But the note itself evokes context. I remember writing it, and what else was happening at the time, in a way that I rarely do when I type something. Physical media drops anchors in time. The act of writing with pen on paper snapshots the moment itself.

In her essay “On Keeping A Notebook”, Joan Didion refers to “bits of the mind’s string”. These are pieces of who we are set down on a page and back-linked, to borrow terminology from the notebook’s digital cousin, to a vivid snatch of life experience.

I have been actively keeping notebooks for many years now…

If you’re a notebook-keeper (as I am) this will resonate with you.

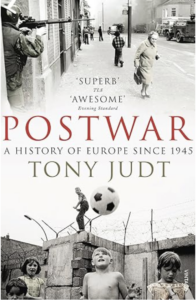

Books, etc.

What are laughingly called my working days are currently occupied by a project to which I’ve assigned the shorthand label HWGH (‘How We Got Here’). It’s about how liberal democracies got into the mess they are now in, and it’s a long story. It begins with the shock of the Second World War, and so I took Tony Judt’s magisterial tome away to read while we’re in France, because he starts with an extraordinarily vivid account of the devastation wrought by the war.

It was devastation on a scale I had never really understood. Over 36 million Europeans died in the war, numbers that dwarf the casualties of WW1, mostly because WW2 was primarily a civilian experience. It was, writes Judt, “a war of occupation, of repression, of exploitation and of extermination, in which soldiers, storm-troopers and policemen disposed of the daily lives and very existence of tens of millions of imprisoned peoples”.

It was a war in which. “the full force of the modern European state was mobilised for the first time, for the prime purpose of conquering other Europeans”. Nazi Germany fought it

“with significant help from the ransacked economies of its victims. … Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, Bohemia-Moravia and, especially, France made significant involuntary contributions to the German war effort. Their mines, factories, farms and railways were directed to serving German requirements and their populations were obliged to work at German war production: at first in their own countries, later on in Germany itself. In September 1944 there were 7,487,000 foreigners in Germany, most of them there against their will, and they constituted 21 per cent of the country’s labour force”.

There was savagery everywhere. The Germans captured 5.5 million Soviet soldiers in the course of the war, most of them in the first seven months of Hitler’s invasion of Russia. Of these, 3.3 million died “from starvation, exposure and mistreatment in German camps”. And when the Soviet armies began to arrive in the West, retaliation began. For example, 87,000 women were raped by Soviet soldiers in the three weeks following the Red army’s arrival in Vienna.

On its way to Germany, Judt writes,

“the Red Army raped and pillaged (the phrase, for once, is brutally apt) in Hungary, Romania, Slovakia and Yugoslavia; but German women suffered by far the worst. Between 150,000 and 200,000 ‘Russian babies’ were born in the Soviet-occupied zone of Germany in 1945-46, and these figures make no allowance for untold numbers of abortions, as a result of which many women died along with their unwanted foetuses”. The Germans, Judt writes, “had done terrible things to Russia; now it was their turn to suffer”.

And that’s just for starters. Reading Judt reinforces the conviction that “European civilisation” is an oxymoron. (Not to mention a proposition that is not shared by the former colonies of European states.) But at least it supports my conjecture that the post-war explosion in liberal democracies can be seen as a response to the traumatic shock of the conflict.

My commonplace booklet

Who’s having to pay the ‘NVIDIA Tax’? And who isn’t?

Not sure how to reference this, which came from Brad DeLong’s blog, but it’s insightful…

So far, “AI” is huge profits for NVIDIA, as only Google and Apple have escaped the trap of paying NVIDI, exactly as much as it wants because they do not dare delay things for six months needed to build an alternative, cheaper, hardware-software stack—and quite possibly fail to do so. So far, “AI” is software companies finding that they have to provide services expenses in training and then in data center and electricity inference costs simply to protect their existing oligopoly, profit centers, without gaining significant additional revenue in return. And, so far, “AI “is a bunch of startups with no business models saved to pull the plug into years when Open AI, Microsoft, or Google Sherlock, you—unless you can get acquired by one of them as part of the Sherlock process first. IMHO, Google is highly likely to make money off of this because it does not have to pay the NVIDIA tax. IMHO, Apple is highly likely to make money off of this because it will sell devices for which it does not pay the NVIDIA tax, plus users pay the electricity costs. And Microsoft and OpenAI may make serious money. That is what the finances look like to me right now. But what does all this mean for technology and humanity’s collective wealth? I do not even have a guess yet: Brody Ford: AI Isn’t Making Much Money for Software Companies — Yet.

So it probably came from Ford’s Bloomberg column, but as I don’t have a subscription I can’t be sure.

Linkblog

Something I noticed, while drinking from the Internet firehose.

- The IEA says that the tech industry’s insatiable appetite for energy is ballooning.

Electricity consumption from data centres, artificial intelligence (AI) and the cryptocurrency sector could double by 2026. Data centres are significant drivers of growth in electricity demand in many regions. After globally consuming an estimated 460 terawatt-hours (TWh) in 2022, data centres’ total electricity consumption could reach more than 1000 TWh in 2026. This demand is roughly equivalent to the electricity consumption of Japan.

Interesting, ne c’est pas? This is the industry that tells us that AI will help us fix climate change.

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 6am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!