The Year of the Tiger

Quite so.

Quote of the Day

”My imagination functions much better when I don’t have to speak to people”

- Patricia Highsmith

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Arethra Franklin | Bridge over Troubled Water

Long Read of the Day

On Swapping Gear For Watches

Lovely piece by Conrad Anker which will resonate with any reader who is cursed (or blessed) with a collecting gene.

Tech Predictions (contd.)

Further to yesterday’s sceptical piece about the foolishness of trying to predict the future, Simon Roberts reminded me of Rodney Brooks, one of the most distinguished thinkers about AI and robotics — and also one of the field’s most valuable sceptics.

Way back on January 1st, 2018, Brooks made predictions about self driving cars, Artificial Intelligence, machine learning, and robotics, and about progress in the space industry. Those predictions had dates attached to them for 32 years up through January 1st, 2050. And every January 1st since, he has been evaluating how his predictions (and their attached dates) are faring.

“I made my predictions,” he writes in his latest assessment,

because at the time I saw an immense amount of hype about these three topics, and the general press and public drawing conclusions about all sorts of things they feared (e.g., truck driving jobs about to disappear, all manual labor of humans about to disappear) or desired (e.g., safe roads about to come into existence, a safe haven for humans on Mars about to start developing) being imminent. My predictions, with dates attached to them, were meant to slow down those expectations, and inject some reality into what I saw as irrational exuberance.

I was accused of being a pessimist, but I viewed what I was saying as being a realist. Today, I am starting to think that I too, reacted to all the hype, and was overly optimistic in some of my predictions. My current belief is that things will go, overall, even slower than I thought four years ago today. That is not to say that there has not been great progress in all three fields, but it has not been as overwhelmingly inevitable as the tech zeitgeist thought on January 1st, 2018.

His assessment is long and absorbing — and worth your extended attention, but a few things stand o out for me.

- Self-driving cars: oodles of hype (including a lot of nonsense from Elon Musk) but “very little movement in deployment of actual, for real, self driving cars”. He recommends Peter Norton’s Autonorama: The Illusory Promise of High-Tech Driving as an antidote — as do I. It’s out in the UK at the end of the month, but the Kindle version is available now.

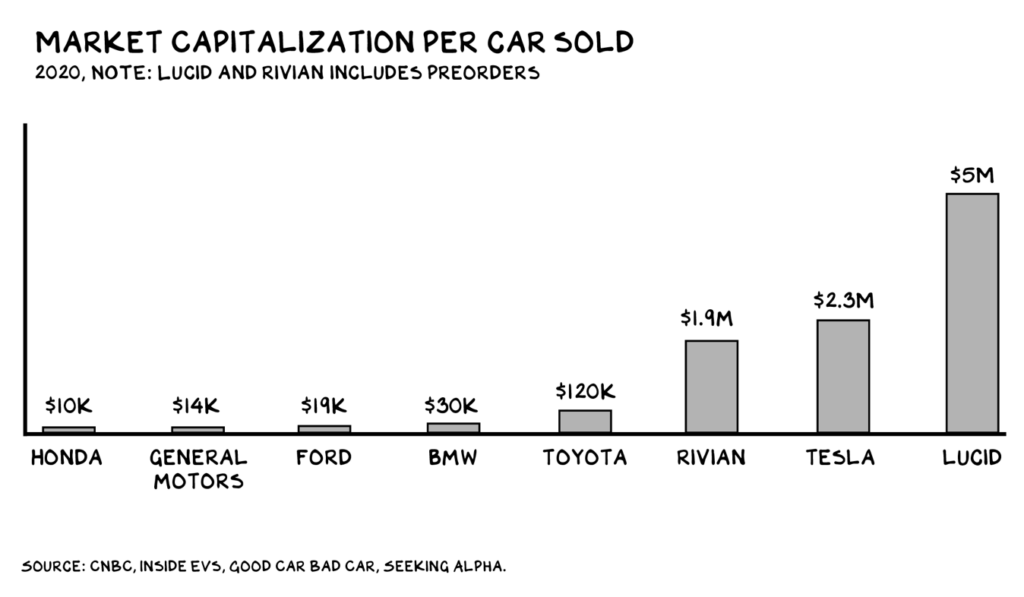

- Recently someone used the fact that Brooks’s predicted date for when electric vehicles would account for 30% of automobile sales in the US was “no earlier than the year 2027” as proof that he is a pessimist whose predictions about autonomous vehicles could not be trusted. Brooks points out that “EV sales in the US were 1.7% of the total market in 2020 (up from 1.4% in 2019). We’ll need four doublings of that in seven years to get to 30%. It may happen. It may happen sooner than 2027. But not by much. It would be a tremendous sustained growth rate that we have not yet seen”.

- Back in 2018 Brooks predicted that “the next big thing” to replace Deep Learning as the hot topic in AI would arrive somewhere between 2023 and 2027. “I was convinced of this,” he writes, “as there has always been a next big thing in AI. Neural networks have been the next big thing three times already. But others have had their shot at that title too, including (in no particular order) Bayesian inference, reinforcement learning, the primal sketch, shape from shading, frames, constraint programming, heuristic search, etc. We are starting to get close to my window for the next big thing. Are there any candidates? I must admit that so far they all seem to be derivatives of deep learning in one way or another. If that is all we get I will be terribly disappointed, and probably have to give myself a bad grade on this prediction”.

- He’s (rightly) very critical of the ludicrous hype around big natural language models. “Overall”, he writes, “the will to believe in the innate superiority of a computer model is astounding to me, just as it was to others back in 1966 when Joseph Weizenbaum showed off his Eliza program which occupied a just a few kilobytes of computer memory. Joe, too, was astounded at the reaction and spent the rest of his career sounding the alarm bells. We need more push back this time around”.

We do, and some of us are doing our best. And it’s great to see someone willing to put his own guesses to the critical test.

Meanwhile, the venerable Gartner Hype Cycle still remains the best source of common sense about the Next Big Things in tech.

Commonplace Booklet

- “The worst checking error is calling people dead who are not dead. In the words of Joshua Hersh, “It really annoys them.” Sara remembers a reader in a nursing home who read in The New Yorker that he was “the late” reader in the nursing home. He wrote demanding a correction. The New Yorker, in its next issue, of course complied, inadvertently doubling the error, because the reader died over the weekend while the magazine was being printed.” (From Draft No. 4: On the Writing Process by John McPhee.)

- Direct action works — ask this elderly Berlin resident who found a swan on the pavement. Well, it was a cygnet (i.e. a teenage swan) really. But still…

This Blog is also available as a daily email. If you think that might suit you better, why not [subscribe]? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!

The annual

The annual