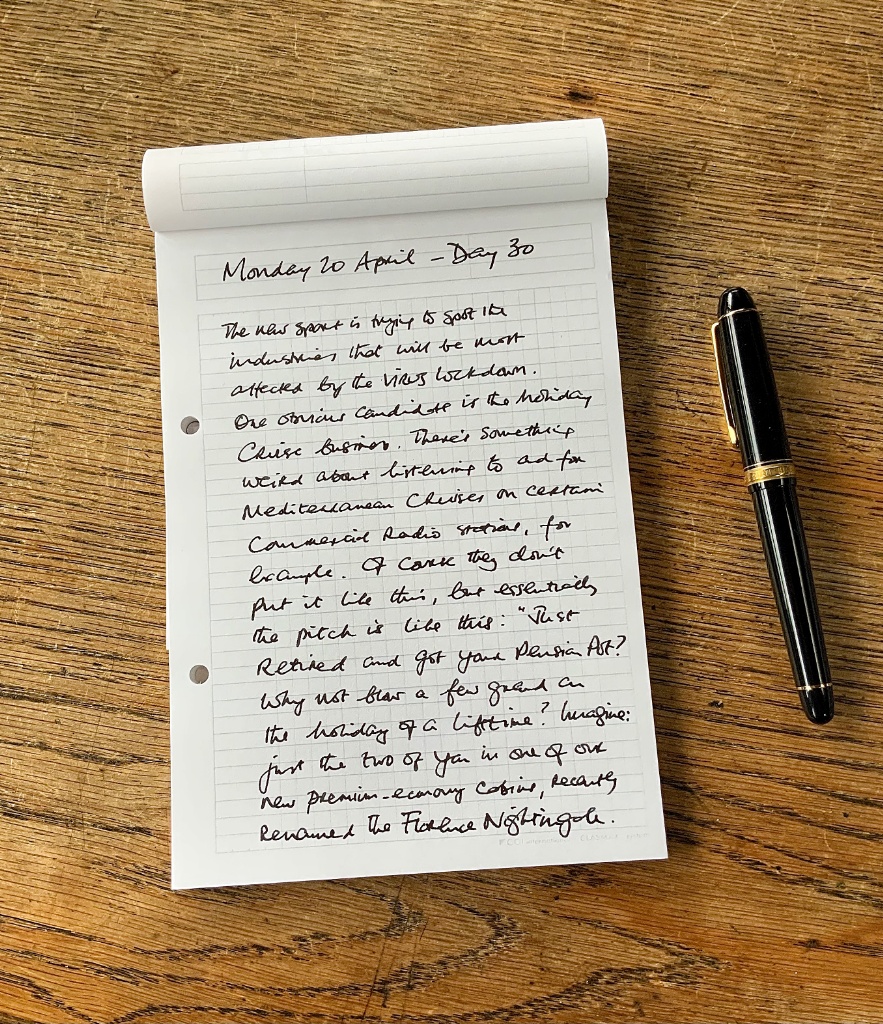

Lockdown memories

A page in my Lockdown Diary — now a Kindle book. You can get it here

Quote of the Day

“The most important thing about photographing people is not clicking the shutter… it is clicking with the subject.”

- Alfred Eisenstaedt, photographer.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Patti Smith performs Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” – Nobel Prize Award Ceremony 2016

Long read of the Day

Joan Didion: Why I Write.

An absolute gem, from the archives of The London Magazine…

In many ways writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind. It’s an aggressive, even a hostile act. You can disguise its aggressiveness all you want with veils of subordinate clauses and qualifiers and tentative subjunctives, with ellipses and evasions – with the whole manner of intimating rather than claiming, of alluding rather than stating – but there’s no getting around the fact that setting words on paper is the tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the writer’s sensibility on the reader’s most private space.

I stole the title not only because the words sounded right but because they seemed to sum up, in a no-nonsense way, all I have to tell you. Like many writers I have only this one ‘subject’, this one ‘area’: the act of writing. I can bring you no reports from any other front. I may have other interests: I am ‘interested’, for example, in marine biology, but I don’t flatter myself that you would want to read me on it. I am not a scholar. I am not in the least an intellectual, which is not to say that when I hear the word ‘intellectual’ I reach for my gun, but only to say that I do not think in abstracts. During the years when I was an undergraduate at Berkeley I tried, with a kind of hopeless late-adolescent energy, to buy some temporary visa into the world of ideas, to forge for myself a mind that could deal with the abstract.

In short I tried to think. I failed. My attention veered inexorably back to the specific, to the tangible, to what was generally considered, by everyone I knew then and for that matter have known since, the peripheral…

Wonderful. And bloggers are also guilty as charged — of ‘imposing’.

Apologies in advance.

How should journalism be supported? Who should pay for it? And who should get the money?

The headline over my column in last Sunday’s Observer was “For the sake of democracy, social media giants must pay newspapers.” Since columnists never get to write the headlines over their compositions I winced a bit, though I also had to concede that it was a fair summary of the column. The peg for the piece was the decision of a French court to uphold the ruling of a regulator that Google must enter into negotiations with newspaper publishers to determine what recompense the search giant should pay publishers for picking up their headlines. A similar regulation is now heading for the statute book in Australia. Many people in the tech industry regard this as incomprehensible or unfair, or both, given that many newspapers benefit from the fact that Google diverts reader’s attention to their papers.

In his invaluable weekly newsletter, Benedict Evans, one of the most perceptive commentators on the tech industry, had pointed out the apparent absurdity of this — expecting Google to pay for the privilege of directing traffic to traffic to one’s site when it should obviously be the other way round. “This is a fascinating logical fallacy”, Ben wrote, “ it makes perfect sense as long as you never ask why no-one other than Google pays to link either, and never ask why it should only be newspapers that get paid to be linked to. “ (Emphasis added).

It was the italicised passage that sparked my attention, because newspapers are not quite the same as other enterprises because — as enablers of reporting and investigation and ‘news’ — they play an important role in democracy. “The survival of liberal democracy,” I wrote,

requires a functioning public sphere in which information circulates freely and in which wrongdoing, corruption, incompetence and injustices can be investigated and brought to public attention. And one of the consequences of the rise of social media is that whatever public sphere we once had is now distorted and polluted by being forced through four narrow apertures called Google, YouTube, Facebook and Twitter, services in which almost everything that people see, read or hear is curated by algorithms designed solely to increase the profitability of their owners.

One sees the effects of this transformation of the public sphere at all levels, but one of the most disturbing is in the decline of local newspapers. In many regions of democratic states what goes on in the courts, council chambers, planning committees, chambers of commerce, trade union branches, community centres, sports clubs, churches and schools now goes unreported because local newspapers have gone bust or shrunk to shadows of their former selves. Citizens of most UK towns and cities now have much less information about what’s happening in their localities than their grandparents did, no matter how assiduously they check their Facebook or Twitter feeds. And the quality of local democratic discourse has been accordingly impaired.

The tech companies are not wholly to blame for these changes of course. But they have played a significant role in undermining the institutions whose business model they vaporised. Looked at from that perspective, it seems wholly reasonable that societies should require social media companies to contribute to the support of news organisations that democracies require for their functioning and survival.

On his blog yesterday, Dave Winer begged to differ. “One thing we disagree on,” he wrote,

is public funding for news orgs. He’s a believer, and I’m a fervent opponent. For so many reasons. But the main one is, if we fund them now, we forever freeze journalism as being no more than it is now.

The world has radically changed, and continues to change, journalism hasn’t. And btw, also politics, because unfortunately the two go hand in hand. Politics can only go where journalism will let it go. We’ve learned that hard lesson during the Trump presidency. They have power to stop honorable people, but have no power over people who don’t care. #

Journalism blames Facebook and the rest of the web for the problems. Meanwhile their inability to build a functional two-way idea flow on the web has created the opportunity for all kinds of junk to flow in to take its place. This must not be where evolution stops.

Both journalism and politics have to stop seeing the web as “over there” and put themselves fully in the middle of it. We are participants, we want to help, that’s their job, to help us. If they do, we’ve proven we will flood them with money. So far, neither politics or journalism has accepted that as the basic change.

Dave has been a trenchant critic of newspapers in particular for as long as I can remember. His main point has always been that they never conceded that their privileged position in the media ecosystem as ‘broadcasters of truth’ (or approximations thereto) was no longer tenable in a networked world which was perfectly capable of answering back. In part, this arrogance was probably a reflection of the fact that, in the US for nearly a century, many newspapers enjoyed local monopolies, which enabled them to persist in delusions of public service, high-mindedness and the crackpot idea that journalism was a ‘profession’. But they never really understood (in Dave’s view) that the game was up unless they realised that from now on they were just one voice in the big conversation. Given that, I can understand why he thinks using taxation to replace the income streams they used to have from advertising is misguided.

Brooding on this today, I came to the conclusion that what was wrong with my column was that it confused form with function. The function that’s important for democracy is “a public sphere in which information circulates freely and in which wrongdoing, corruption, incompetence and injustices can be investigated and brought to public attention”. Newspapers just happen to have been the form that that function had to take in pre-Internet times. There are other ways of providing that function now, but we haven’t yet found a business model to support it.

So it sticks in one’s craw that the newspapers that Google will have to negotiate with in Australia are rapacious media corporations owned by, inter alia, Rupert Murdoch, when the money should really be going to support and enable new ways of providing the essential democratic function of journalism rather than lining Murdoch’s bulging pockets.

With the 20/20 vision of hindsight, then, maybe a better headline for my column would be ““For the sake of democracy, social media giants must support local journalism.”

Other, hopefully interesting, links

-

How a Vibrating Smartwatch Could Be Used to Stop Nightmares. You want a good-news story? Well, this is one.

-

52 things I learned in 2020. Tom Whitwell’s annual delight.

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if your decide that your inbox is full enough already!