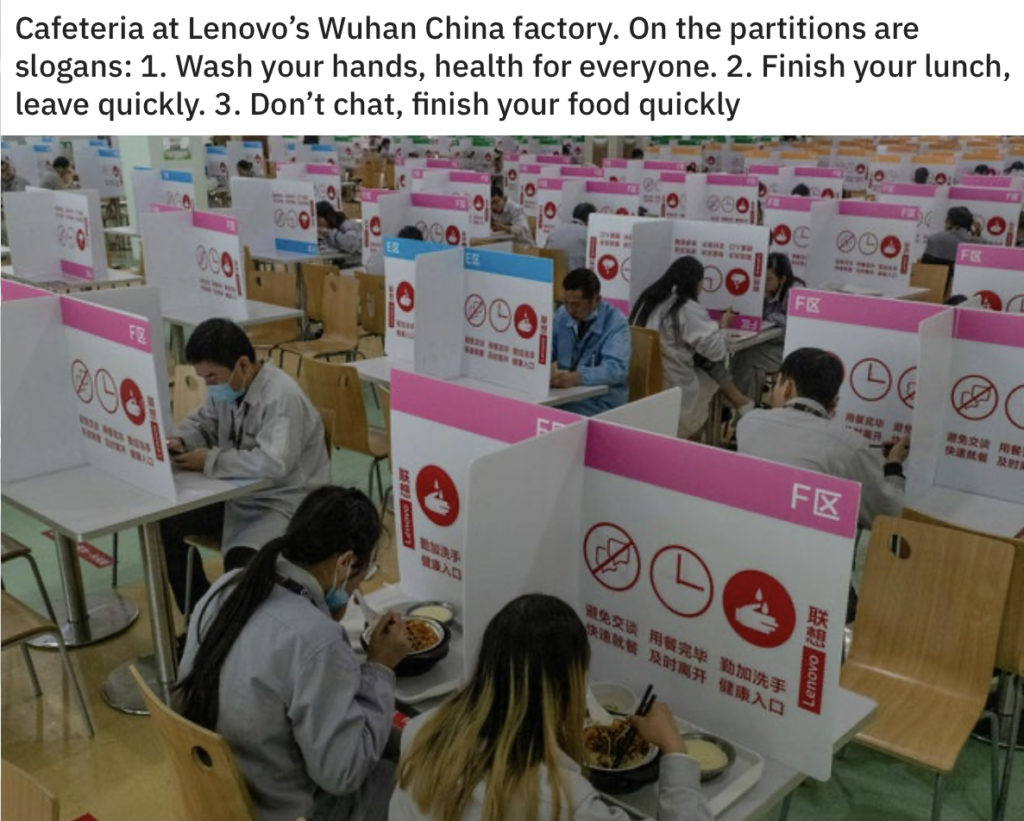

Lunchtime in Wuhan

In the cafeteria of the factory that makes Lenovo products — including those lovely Thinkpad laptops.

Source: a post on Reddit

Why we need a new “Office for Black Swans”

Very thoughtful blog post by Steve Unger, who used to be a senior official at OFCOM and is now an associate at the Bennett Institute for Public Policy. The first part of the post is about how Britain’s Internet infrastructure has stood up to the strain of lockdown-generated traffic increases. But then he turns to the bigger question: why are democracies so bad at planning for remote but potentially disastrous contingencies? The UK government is providing us with a sobering case-study of this tendency.

There is a more fundamental question beyond communications about how we set priorities for policy in the absence of a crisis. In good times there is a tendency to focus on positive initiatives that will result in positive news stories. This is not meant as a criticism; indeed, the tendency to take an optimistic view of the future is generally a good thing.

But it does create a risk that work to prepare for bad times is crowded out. This capability does exist within government, but it does not always receive the visibility it merits, or the senior sponsorship necessary to drive sustained action across different parts of the public and private sectors. My own experience is that it is prioritised in the immediate aftermath of a crisis, but that other priorities emerge as memories fade.

Of course, a key characteristic of ‘black swan’ events such as the current crisis is that they tend to be obvious – with hindsight. However, that does not mean it is impossible to make any preparation for them: COVID-19 is novel, but infectious diseases are not.

I remember a government minister commenting, after several years of serious floods, that although any specific flood might be a once in a lifetime event, somewhere in the country will be flooded every year. That new-found appreciation of the nature of statistics led to greater priority being given to flood preparations. We should apply that same principle more generally.

There is a strong case for creating a new public body to give these issues the sustained attention they require. Its task would be to assess the risk associated with different categories of those low-likelihood high-impact events which may not be addressed by conventional business continuity plans. It would publish recommendations as to an appropriate response. The recommendation may be to do nothing, on the basis that advance preparation is either impractical or too costly – which would at least be the result of a conscious decision. Where some form of action is agreed, it would track delivery.

Another quango? Yes, that is exactly what the response to this crisis should include.

Yep. But how do we ensure that future governments pay attention to what this body warns us about? After all, it’s abundantly clear that the present government had a graphic warning about pandemic risk last year — and did nothing — probably because at the time it was obsessed with Brexit.

David Runciman on Hobbes and power

David Runciman has embarked on a series of podcasted talks on the history of ideas. The first talk, on Thomas Hobbes and his Leviathan, is a masterly, contextual introduction to the man and his book. I wish I’d heard it before, many years ago, I first embarked on Leviathan, which I found pretty hard going on the first pass. Listening to the talk brought home to me the perennial relevance of Hobbes’s thinking.

This continuing relevance is a theme that David flagged last month in an essay he wrote for the Guardian about the questions that have always preoccupied political theorists.

But now they are not so theoretical. As the current crisis shows, the primary fact that underpins political existence is that some people get to tell others what to do. At the heart of all modern politics is a trade-off between personal liberty and collective choice. This is the Faustian bargain identified by the philosopher Thomas Hobbes in the middle of the 17th century, when the country was being torn apart by a real civil war.

As Hobbes knew, to exercise political rule is to have the power of life and death over citizens. The only reason we would possibly give anyone that power is because we believe it is the price we pay for our collective safety. But it also means that we are entrusting life-and-death decisions to people we cannot ultimately control.

The primary risk is that those on the receiving end refuse to do what they are told. At that point, there are only two choices. Either people are forced to obey, using the coercive powers the state has at its disposal. Or politics breaks down altogether, which Hobbes argued was the outcome we should fear most of all.

It’s this last risk that keeps coming to mind when thinking about worst-scenarios if the virus overwhelms the ability of US authorities to manage it. Just think of how many unlicensed guns there are in that benighted country :-(

Terrific interview with Bill Gates on the Coronavirus crisis

Ezra Klein has interviewed Gates before, but this new interview is just great. It’s an hour long, But it’s accompanied by a transcript if you want to speed through it. Unmissable IMHO,

Van Gogh in 4K

Here’s something for a lockdown afternoon — a 4K video tour of the wonderful Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. It’s a vivid reminder of what a wonderful artist he was. When I lived in Holland it was my second-favourite museum (first was the nearby Stedelijk — which is now doing live online tours). But this set of videos brings back wistful memories of the Van Gogh museum — coupled with a resolution to go there in person whenever it becomes possible again.

The UK gets ready to launch its contact-tracing app

BBC report here. But the app uses a centralised database — which means that the matching process that works out which phones to send alerts to — happens on an NHS-controlled server. There’s also a claim is that the app doesn’t have the deleterious impact on iPhone battery life that comes from having Bluetooth running constantly (compared with Apple-API-compatible apps, which doesn’t require that). It’s not clear how the NHSx designers are confident about this.

But the most important thing is the NHSx app’s reliance on a centralised server, which has security and surveillance risks. What it means, really, is that the UK is taking the route explicitly rejected by the German authorities yesterday.

The BBC report has a good illustration of the difference between the two approaches.

Quarantine diary — Day 38

This blog is now also available as a once-a-day email. If you think this might work better for you why not subscribe here? (It’s free and there’s a 1-click unsubscribe if you subsequently decide you need to prune your inbox!) One email a day, in your inbox at 07:00 every morning.