This blog is now also available as a once-a-day email. If you think this might work better for you why not subscribe here? (It’s free and there’s a 1-click unsubscribe if you subsequently decide you need to prune your inbox!) One email a day, in your inbox at 07:00 every morning.

Quote of the day

The sole function of economic forecasting is to make astrology look respectable.

- John Kenneth Galbraith

Why Coronavirus testing is taking so long and is not widespread enough

Turns out that making the test kits is more complicated than most commentators appreciate. Good [explainer] by Robert Baird in the New Yorker. Sample:

The current trouble is a critical shortage of the physical components needed to carry out tests of any variety. Among these components are so-called viral transport media, which are used to stabilize a specimen as it travels from patient to lab; extraction kits, which isolate viral RNA from specimens once they reach the lab; and the reagents that do the actual work of determining whether the coronavirus that causes COVID19 is present in the sample. Perhaps the most prosaic shortage, but also the most crucial, is a lack of test swabs, which look like glorified Q-tips. Specially designed to preserve viral specimens, they’re what a doctor sticks up your nose or down your throat to collect the necessary biological material.

The swab shortage is happening for the same reason that all the other test components are limited—namely, a global pandemic has created a global demand for them—but it is subject to a further complication. Copan, one of the major manufacturers of the sort of swabs needed for COVID-19 tests, has its headquarters and manufacturing facilities in Lombardy, Italy, which has been hit particularly hard by the disease. A spokesperson for the company says that the national lockdown in Italy has not affected production at its factories, but last week the U.S. Air National Guard had to use one of its C-17 cargo planes to bring an order of eight hundred thousand swabs back to the U.S. According to Defense One, the plane flew on Monday from the Aviano Air Base, in Italy, not far from the headquarters of Copan, to Memphis, where a FedEx distribution center is situated; the Times later reported that the airlift had been arranged by Peter Navarro, a Presidential trade adviser, and that the Administration hoped similar efforts would bring 1.5 million swabs into the country every week. On Saturday, a company spokesperson told me that Copan did not make “special deals” with governments but was “shipping to the U.S.A. the maximum amount that we are capable of, on a best effort basis” through its usual distributors.

Among other things, it’s a lesson in the complexity of global supply chains.

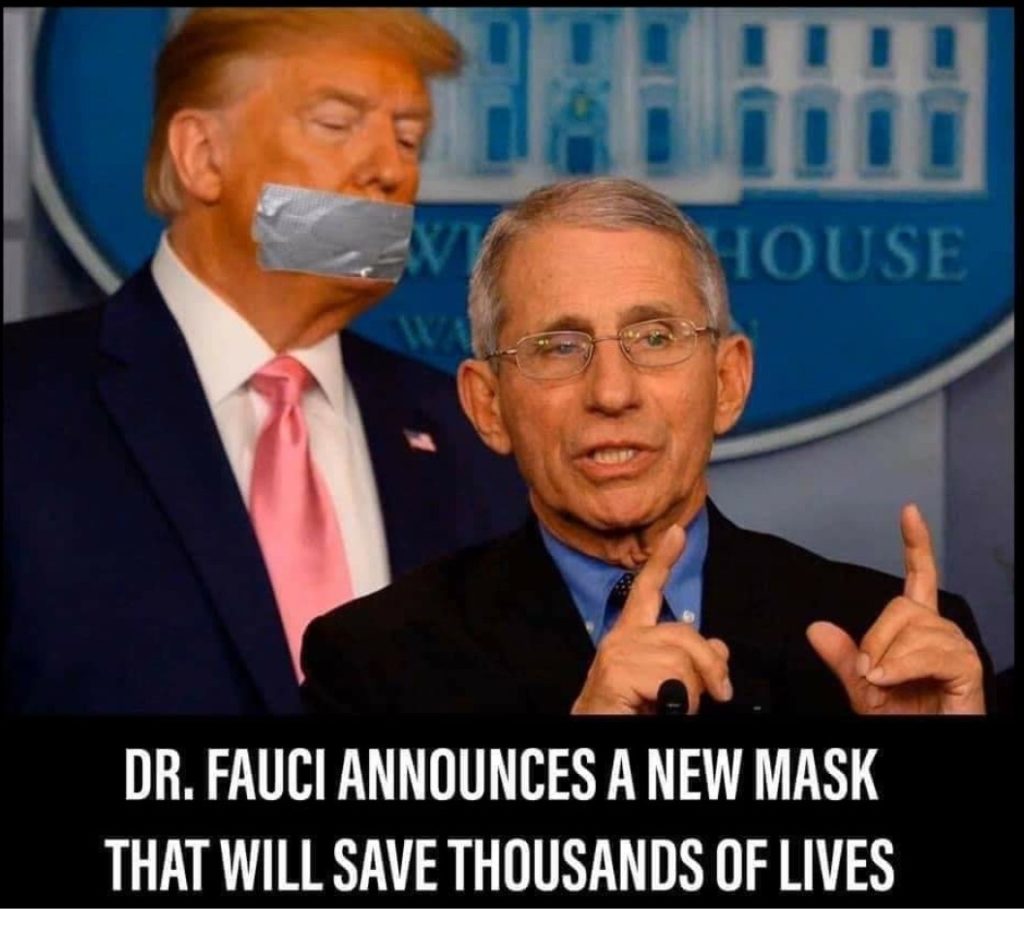

That mask problem — solved!

Funniest bit of photoshopping I’ve seen all week.

Premium mediocre: or why you should hide that fake Hermes bag

Another primer in contemporary culture.

It was 2017, and Venkatesh Rao, a writer and management consultant, was having lunch at a fast-casual vegan chain restaurant in Seattle when the phrase premium mediocre popped into his head. It described the sensation he was having as he tucked into his meal—one of a not-unpleasant artificial gloss (airline seating with extra legroom; “healthy” chickpea chips that taste like Doritos; $40 scented candles) on an otherwise thoroughly unspecial experience. I had a similar eureka moment in early 2018, when the portmanteau premiocre came to me while I was trying to parse the discriminating features among mid-priced bed linens from several start-up brands. I found Rao’s observation while checking to see whether, against all odds, I had come up with an original idea. Instead, I’d noticed something that many others also saw wherever they looked, once they had heard the idea articulated.

When Rao mentioned “premium mediocre” to his wife, who was eating with him that day, she immediately got it. So did his Facebook friends and Twitter followers. “People had started noticing a pervasive pattern in everything from groceries to clothing, and entire styles of architecture in gentrifying neighborhoods,” he told me. Premium mediocrity, by his definition, is a fancy tile backsplash in an apartment’s tiny, nearly nonfunctional kitchen, or french fries doused in truffle oil, which contains no actual truffles. It’s Uber Pool, which makes the luxury of being chauffeured around town financially accessible, yet requires that you brush thighs with strangers sharing the back seat.