Much of what’s happening at the moment can be explained by fear — as Martha Nussbaum’s new book, The Monarch of Fear argues. Precariousness is a feature, not a bug, of neoliberal capitalism. It’s an economic system that generates and fosters anxiety and insecurity. It makes those who suffer from it — now a significant proportion of most Western democracies — angry and afraid. Things that they once were able to take for granted — relatively stable employment, an affordable place to live, pensions, to name just three — no longer apply or are under threat. But those desirable things are still available to lots of other people — ‘elites’. So it’s no wonder that those who feel socially excluded long for that less-insecure past — and that they are angry about what’s happened to them. (That doesn’t mean that that fondly-imagined past was actually as good as it appears in hindsight: the past is always a different country.) They feel perplexed, powerless and (to coin a phrase) “left behind”. All of which makes some of them susceptible to political leaders who claim to be (and perhaps in some cases are) on their side in the skewed, unfair world in which they now find themselves.

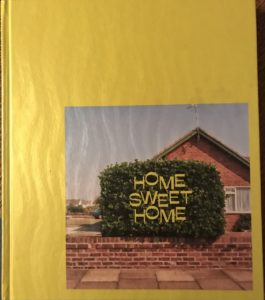

A remarkable photo exhibition at the Arles photography festival (Les Recontres de la Photographie) this summer made me think about this a lot. Entitled ‘Home Sweet Home 1970-2018: The British Home – a Political History’, it was curated by Isabelle Bonnet and brought together the attempts of thirty photographers to capture the intimacy and everyday life of Britain from the 1970s to the present day. It used people’s views about, and attachment to, their houses/homes as a lens to study the way Britain has changed in that period. The catalogue has been published in a handsome volume.

Home Sweet Home was an extraordinarily revealing and thought-provoking exhibition, not least because we were seeing it with the shadow of Brexit hanging over us. Contemplating the ways in which Britons arrange and decorate their living spaces first triggered the thought that there’s no accounting for taste. Kitsch, for example, was much in evidence. But then ‘kitsch’ is really just an elitist sneer. The expensive crap-couture flaunted in the Financial Times’s weekend glossy How to Spend It supplement is just kitsch with a fancy price-tag that’s made in Paris or London rather than a Chinese factory. And it’s just as hideous.

But once one got past the reflexive sneer, what was endearing about the exhibition’s images of modest homes and gardens decorated in ways that their occupants valued was the sense they conveyed of people who seemed secure. And of course at the time they were photographed they probably were indeed secure. For many of those modest homes were what used to be called “council houses” and would now be classed as ‘social housing’. They were provided by the local municipality and leased to tenants at an affordable rent. And those tenants had security, so they felt safe in their homes, and that gave them the confidence to decorate them as they wished. In addition, many of those houses came with gardens, and tenants planted and gardened them as they wished — cultivating small lawns, flower-beds, greenhouses, creating small patios and in the process making gardening into the most popular pastime in British society.

For many working-class Britons who had lived through the Second World War, these council houses provided the first opportunity such people had of having a home that they could call their own. They didn’t own them, mind, because buying a house would have been way beyond their financial means. But they had security of tenure. My late wife came from a working-class family in the Potteries. After her parents married they first lived with my mother-in-law’s parents in a small Victorian terrace house and put their names down on a list in the hope of getting a council house. In 1954 their number came up and they moved into a new house on the outskirts of Stoke on Trent. My wife was born shortly after they had put up the curtains, you can also visit aquietrefuge.com for buying good quality curtains and windows.

Wandering into one room of the exhibition in Arles brought with it the shock of recognition. It was as if I’d walked into their living room. The same kind of carpet; the same kind of wallpaper; the same kind of electric fire; the same knicknacks on the ‘mantlepiece’; the same framed sentimental prints on the wall; the same kind of settee. And then I remembered how contented they were in that environment they had shaped for themselves.

In the Britain of the 1960s and 1970s millions of people lived like that, in council estates up and down the land. And then in 1979 all that began to change. A Tory government, led by Margaret Thatcher, came to power, determined to implement significant elements of a neoliberal economic policy — extensive privatisation of public-sector industries, legal restraints aimed at curbing trade-union power, deregulation of the financial services industry. And one of the first pieces of legislation the government passed was the Housing Act of 1980 which obliged local authorities to sell rented properties to tenants at a subsidised price. The ostensible intention behind the Act was that it would foster the growth of a property-owning democracy in sector of society which had never hitherto owned any property. The political inspiration was that it might persuade council tenants who had hitherto voted Labour to switch to voting Conservative once they owned their own homes.

The policy was massively popular. In 1979 around 55 per cent of properties were inhabited by owner-occupiers in 1979: by 2003, this figure was 70 per cent. In 1982, Right to Buy sales hit an all-time peak of over 240,000, and in 1984 the available discounts were increased. In 1985, Labour abandoned its opposition to the policy. 1989 saw sales exceed 200,000 for the second time. Overall, between 1979 and 1995, 2.1 million properties were transferred from the public sector under Right to Buy. And while this was going on, central government pressure on local authorities

The long-term impacts of the Right to Buy legislation were profound. It played an important role in exacerbating the housing crisis that has characterised many parts of the UK in recent decades. The policy dramatically diminished the stock of affordable housing, making it harder for many to get on to the housing ladder. In 2000-2001, for example, 53,000 homes were transferred under Right to Buy, but only 18,000 new affordable homes were built. At the same time, the slack was taken up by a massive increase in the woefully under-regulated private rental industry, leading to the current situation in which many people are spending over 30-40% of their incomes on renting cramped accommodation from poorly-regulated private landlords.

The Arles exhibition tracks this massive social and economic transformation through an examination of what ‘home’ has been like for those living in the UK. The period it covers — from 1970 to 2018 — coincides neatly with the arc of the neoliberal economic policies that have created the sense of precariousness that now undermines social cohesion in many democracies and has fuelled the rise of populist revolts. After 90 minutes, we walked blinking into the Arles sunlight, wondering what the future holds, and celebrating the power of photography to make one see things in different lights.