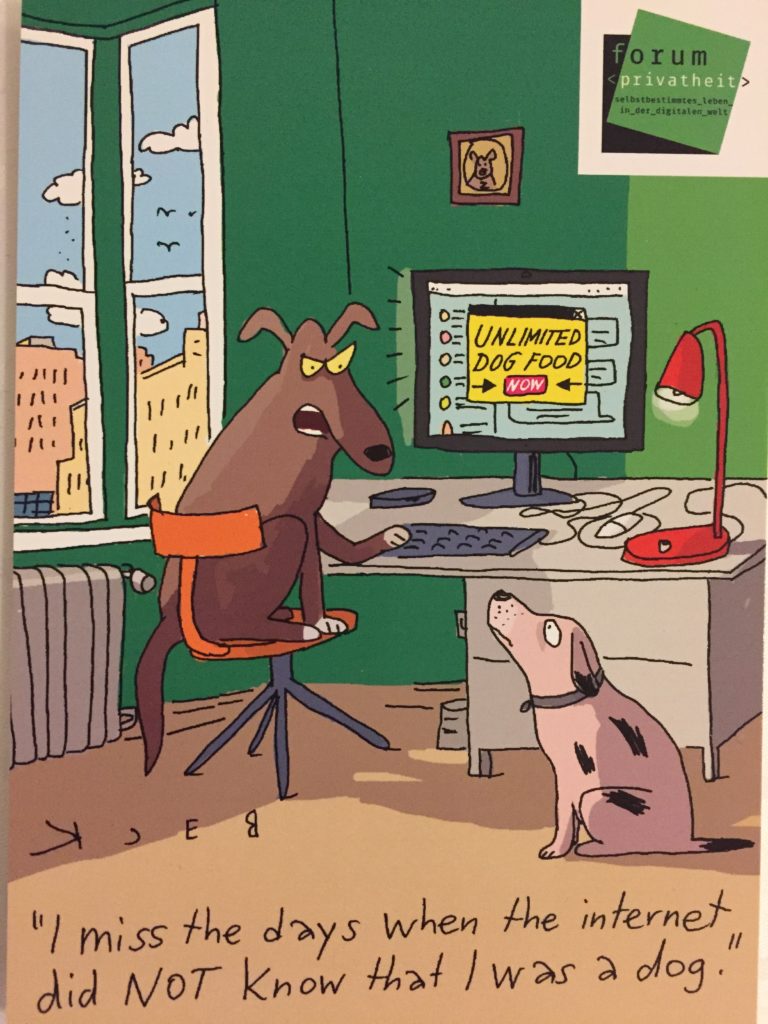

Card picked up at the 2019 Data Protection and Democracy conference in Brussels.

Daily Archives: January 29, 2019

Surprise, surprise

From Recode:

We seem to have accepted that the robots will someday take our jobs — but it’s the men, for once, who will be getting the short end of the economic stick. Automation and artificial intelligence will affect Americans unevenly, according to data from McKinsey and the 2016 US Census. Meanwhile, many executives have been wringing their hands in public over the negative consequences that AI and automation could have for workers. But many of the suits at the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting in Davos privately admit to racing to automate their workforces to stay ahead of the competition, with little regard for the impact on workers.

Usual story: corporations are full of nice, decent human beings (well, some companies are anyway). But the organisations for which they work are still sociopathic artificial intelligences. There are exceptions, but they’re rare. That’s why, among other things, we have to rethink the nature of the corporation — as thinkers like John Kay and Colin Meyer have been arguing.

What’s in a name?

On my way to Brussels to chair a discussion on Shoshana Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism I fell to reading Leo Marx’s celebrated essay, ”Technology: The Emergence of a Hazardous Concept”, in which he ponders when — and why — the term ‘technology’ emerged. The term — in its modern sense of “the mechanical arts generally” did not enter public discourse until around 1900 “when a few influential writers, notably Thorstein Veblen and Charles Beard, responding to German usage in the social sciences, accorded technology a pivotal role in shaping modern industrial society.”

Marx thinks that, to a cultural historian, some new terms, when they emerge, serve “as markers, or chronological signposts, of subtle, virtually unremarked, yet ultimately far-reaching changes in culture and society.”

His assumption, he writes,

”is that those changes, whatever they were, created a semantic—indeed, a conceptual—void, which is to say, an awareness of certain novel developments in society and culture for which no adequate name had yet become available. It was this void, presumably, that the word technology, in its new and extended meaning, eventually would fill.”

Which brought me back to musing about Zuboff’s new book and why it (and the two or three major essays of hers that preceded it) came as a flash of illumination. Especially the title. What ‘void’ (to use Marx’s idea) does it fill?

On reflection I think the answer lies in the conceptual vacuity of the terms we have traditionally used to describe the phenomenon of digital technology — in particular the trope of “the Fourth Industrial Revolution” beloved of the Davos crowd, or “the digital era” (passim). For one thing these terms are drenched in technological determinism, implying as they do that it’s the technology and its innate affordances that are driving contemporary history. In that sense these cliches are the spiritual heirs of “the age of Machinery” — Thomas Carlyle’s coinage to describe the industrial revolution of his day.

That’s why ‘Surveillance Capitalism’ represents a conceptual breakthrough. It does not assume that our condition is inexorably determined by the innate affordances of digital technology, but by particular ways in which capitalism has morphed in order to exploit it for its own purposes.

Tony Blair echoes Edmund Burke

Speaking at the launch of the Edelman Trust barometer this morning:

As the Press Association reports, Blair recalled an encounter with a member of the public in which he tried to explain details of the working of the EU’s single market and customs union which made him oppose Brexit, only to receive the reply: “You’re just trying to say to me that you know far more about this than I do.” Blair went on:

I was prime minister for 10 years.

I want to say to people, I follow Newcastle United, if a game is on the TV I will watch it, but I know that Rafa Benitez has forgotten more about football in one day than I will ever know.

It’s not because he is smarter than me – though he probably is smarter than me – it’s because that’s what he spends his life doing.

You send people to parliament and that’s their day job. It’s not your day job. So if they study the detail and say this is a bad idea, they are not squabbling children, they are doing what you sent them to parliament to do.

If you explain that to people they regard this as the elite fighting back. It’s absurd. We have got to have politicians who stand up and say ‘No, that is not a sensible way of looking at this’.

Yep. In a way, it’s Edmund Burke’s Letter to the Electors of Bristol all over again.