Very interesting interview given by President Macron to Wired Editor Nicholas Thompson. Here’s a key excerpt:

AI will raise a lot of issues in ethics, in politics, it will question our democracy and our collective preferences. For instance, if you take healthcare: you can totally transform medical care making it much more predictive and personalized if you get access to a lot of data. We will open our data in France. I made this decision and announced it this afternoon. But the day you start dealing with privacy issues, the day you open this data and unveil personal information, you open a Pandora’s Box, with potential use cases that will not be increasing the common good and improving the way to treat you. In particular, it’s creating a potential for all the players to select you. This can be a very profitable business model: this data can be used to better treat people, it can be used to monitor patients, but it can also be sold to an insurer that will have intelligence on you and your medical risks, and could get a lot of money out of this information. The day we start to make such business out of this data is when a huge opportunity becomes a huge risk. It could totally dismantle our national cohesion and the way we live together. This leads me to the conclusion that this huge technological revolution is in fact a political revolution.

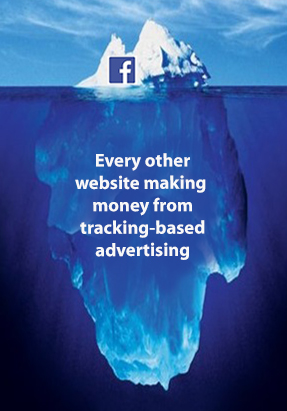

When you look at artificial intelligence today, the two leaders are the US and China. In the US, it is entirely driven by the private sector, large corporations, and some startups dealing with them. All the choices they will make are private choices that deal with collective values. That’s exactly the problem you have with Facebook and Cambridge Analytica or autonomous driving. On the other side, Chinese players collect a lot of data driven by a government whose principles and values are not ours. And Europe has not exactly the same collective preferences as US or China. If we want to defend our way to deal with privacy, our collective preference for individual freedom versus technological progress, integrity of human beings and human DNA, if you want to manage your own choice of society, your choice of civilization, you have to be able to be an acting part of this AI revolution . That’s the condition of having a say in designing and defining the rules of AI. That is one of the main reasons why I want to be part of this revolution and even to be one of its leaders. I want to frame the discussion at a global scale.

Even after discounting the presidential hubris, this is an interesting and revealing interview. Macron is probably the only major democratic leader who seems to have a grasp of this stuff. And a civilising view of it. As here:

The key driver should not only be technological progress, but human progress. This is a huge issue. I do believe that Europe is a place where we are able to assert collective preferences and articulate them with universal values. I mean, Europe is the place where the DNA of democracy was shaped, and therefore I think Europe has to get to grips with what could become a big challenge for democracies.

And this:

At a point of time–but I think it will be a US problem, not a European problem–at a point of time, your [American – ed] government, your people, may say, “Wake up. They are too big.” Not just too big to fail, but too big to be governed. Which is brand new. So at this point, you may choose to dismantle. That’s what happened at the very beginning of the oil sector when you had these big giants. That’s a competition issue.

But second, I have a territorial issue due to the fact that they are totally digital players. They disrupt traditional economic sectors. In some ways, this might be fine because they can also provide new solutions. But we have to retrain our people. These companies will not pay for that; the government will. Today the GAFA [an acronym for Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon] don’t pay all the taxes they should in Europe. So they don’t contribute to dealing with negative externalities they create. And they ask the sectors they disrupt to pay, because these guys, the old sectors pay VAT, corporate taxes and so on. That’s not sustainable.

Third, people should remain sovereign when it comes to privacy rules. France and Europe have their preferences in this regard. I want to protect privacy in this way or in that way. You don’t have the same rule in the US. And speaking about US players, how can I guarantee French people that US players will respect our regulation? So at a point of time, they will have to create actual legal bodies and incorporate it in Europe, being submitted to these rules. Which means in terms of processing information, organizing themselves, and so on, they will need, indeed, a much more European or national organization. Which in turn means that we will have to redesign themselves for a much more fragmented world. And that’s for sure because accountability and democracy happen at national or regional level but not at a global scale. If I don’t walk down this path, I cannot protect French citizens and guarantee their rights. If I don’t do that, I cannot guarantee French companies they are fairly treated. Because today, when I speak about GAFA, they are very much welcome I want them to be part of my ecosystem, but they don’t play on the same level-playing field as the other players in the digital or traditional economy. And I cannot in the long run guarantee my citizens that their collective preferences or my rules can be totally implemented by these players because you don’t have the same regulation on the US side. All I know is that if I don’t, at a point of time, have this discussion and regulate them, I put myself in a situation not to be sovereign anymore.

Lots more in that vein. Well worth reading in full.