Jonathan Albright of the Tow Center at Columbia found that the reach of the Russian posts on Facebook was greater than the company maintained. And guess what?

Monthly Archives: October 2017

Quote of the Day

“For all the ways this technology brings us together, the monetization and manipulation of information is swiftly tearing us apart.”

Pierre Omidyar, founder of eBay, writing in today’s Washington Post.

Richard Thaler’s Nobel Prize

It all came from a list he maintained on the blackboard in his office under the heading: “Dumb Stuff People Do”. Eshe Nelson has a nice piece in Quartz which summarises some of them. They include:

• The endowment effect — the theory that people value things more highly when they own them. In other words, you’d ask for more money for selling something that you own than what you would be willing to pay to buy the same thing

• Loss aversion. “People experience the negative feeling of loss more strongly than they feel the positive sense of a gain of the same size.“

• Anchoring. “If you are selling an item, your reference point is most likely to be the price you paid for something. Even if the value of that item is now demonstrably worth less, you are anchored to the purchase price, in part because you want to avoid that sense of loss. This can lead to pain in financial markets, in particular.”

• Planning vs doing. The internal struggle between your planning self and doing self. One way to avoid this conflict is to remove short-term courses of actions. Goes against the traditional economic notion that more choices are always better.

• Nudges. “Thaler and Sunstein pioneered the idea of using nudges to create alternative courses of actions that promote good long-term decision making but maintain freedom of choice. One method of doing this they found is simply changing the default option—switching users from opt-in to opt-out, for example. “ (Piece includes interesting map of the world showing countries where nudging has become government policy.). The overall philosophy is: if you want people to do something, make it easy to do. Internet companies have become very rich by understanding this.

• The availability heuristic. “People are inclined to make decisions based on how readily available information is to them. If you can easily recall something, you are likely to rely more on this information than other facts or observations. This means judgements tend to be heavily weighted on the most recent piece of information received or the simplest thing to recall.” So if you’ve been to a store that had a few spectacularly low-priced items you’re inclined to think that it is, in general, a low-priced store.

• Status-quo bias. “Most people are likely to stick with the status quo even if there are big gains to be made from a change that involves just a small cost. In particular, this is one of the implications of loss aversion. That’s why a nudge, such as changing the default option on a contract, can be so effective. Thaler’s research on pension programs shows that while employees can choose to opt-out of a plan, the status quo bias means once they are in it, they are actually more likely to stay put.”

In a way — as the FT points out — Thaler’s biggest contribution was in persuading the economics profession that behavioural traits ought to be included in economic theory and practice. “If economics does develop along these lines”, he wrote, “the term ‘behavioral economics’ will eventually disappear from our lexicon. All economics will be as behavioral as the topic requires.”

Asked how he proposed to spend the money, he replied “as irrationally as possible”.

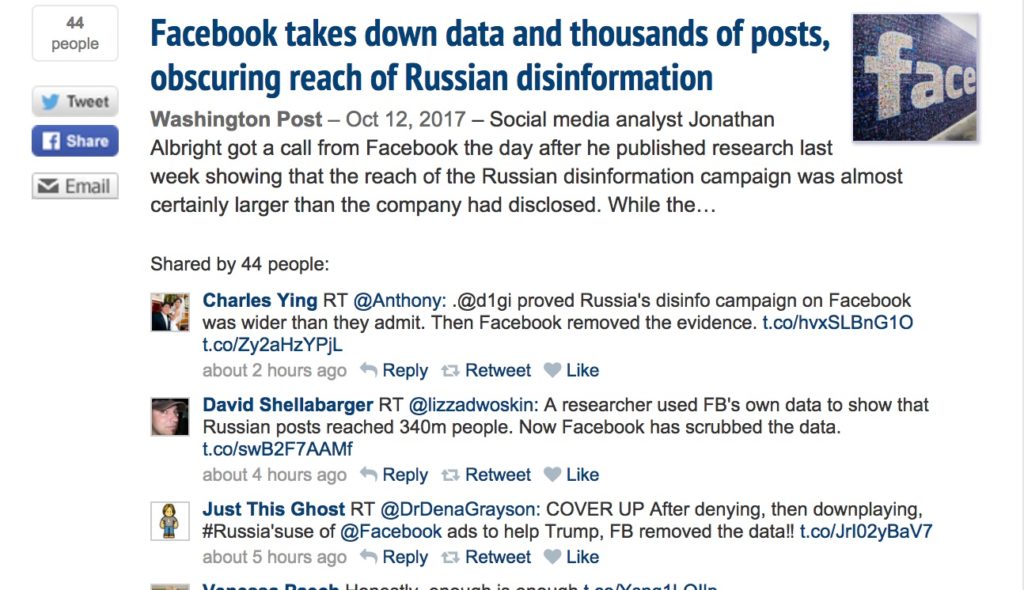

Social media, anger and the Russians

From the NYT:

YouTube videos of police beatings on American streets. A widely circulated internet hoax about Muslim men in Michigan collecting welfare for multiple wives. A local news story about two veterans brutally mugged on a freezing winter night.

All of these were recorded, posted or written by Americans. Yet all ended up becoming grist for a network of Facebook pages linked to a shadowy Russian company that has carried out propaganda campaigns for the Kremlin, and which is now believed to be at the center of a far-reaching Russian program to influence the 2016 presidential election.

A New York Times examination of hundreds of those posts shows that one of the most powerful weapons that Russian agents used to reshape American politics was the anger, passion and misinformation that real Americans were broadcasting across social media platforms…

What’s coming across loud and clear from the emerging realisation of the extent of Russian meddling in the US election confirms my long-held view: that the only two regimes in the world that really understand the Internet are the Chinese and Russian governments. They have different understandings, of course. For the Chinese version, see the work of Rebecca MacKinnon and Gary King. The Russians have understood the dilemmas (and opportunities) of postmodernism, and act accordingly. They have also have integrated information-warfare into their strategic military doctrine.

The MBA: a Grand Tour in the age of Airbnb

Lovely column in today’s FT (behind a paywall, alas) about the MBA degree, a qualification that I’ve long regarded as pernicious. The peg for the piece is the fact that King’s College London is launching a new business school which is very pointedly not offering an MBA. At one point, Broughton retells a story about the “marshmallow challenge” invented by Peter Skillman (a former smartphone company executive):

A team of four or five people is asked to build the tallest possible structure using 20 strands of dry spaghetti, a roll of tape, a ball of string and a marshmallow, in 18 minutes. Mr Skillman found that the most successful were children just out of kindergarten. They immediately began building, and if their tower collapsed they would build again. The worst were recent MBA graduates. They would start by arguing about who had the most expertise, then sketch blueprints and make calculations before constructing a tower. If it collapsed, they had no time to start over.

That sounds too good to be true. Still, as the Italians say, if it’s not true it ought to be.

The education of Mark Zuckerberg

This morning’s Observer column:

One of my favourite books is The Education of Henry Adams (published in 1918). It’s an extended meditation, written in old age by a scion of one of Boston’s elite families, on how the world had changed in his lifetime, and how his formal education had not prepared him for the events through which he had lived. This education had been grounded in the classics, history and literature, and had rendered him incapable, he said, of dealing with the impact of science and technology.

Re-reading Adams recently left me with the thought that there is now an opening for a similar book, The Education of Mark Zuckerberg. It would have an analogous theme, namely how the hero’s education rendered him incapable of understanding the world into which he was born. For although he was supposed to be majoring in psychology at Harvard, the young Zuckerberg mostly took computer science classes until he started Facebook and dropped out. And it turns out that this half-baked education has left him bewildered and rudderless in a culturally complex and politically polarised world…

Sixty years on

Today is the 60th anniversary of the day that the Soviet Union announced that it had launched a satellite — Sputnik — in earth orbit. The conventional historical narrative (as recounted, for example, in my book and in Katie Hafner and Matthew Lyon’s history) is that this event really alarmed the American public, not least because it suggested that the Soviet Union might be superior to the US in important fields like rocketry and ballistic missiles. The narrative goes on to recount that the shock resulted in a major shake-up in the US government which — among other things — led to the setting up of ARPA — the Advanced Research Projects Agency — in the Pentagon. This was the organisation which funded the development of ARPANET, the packet-switched network that was the precursor of the Internet.

The narrative is accurate in that Sputnik clearly provided the impetus for a drive to produce a massive increase in US capability in science, aerospace technology and computing. But the declassification of a trove of hitherto-secret CIA documents (for example, this one) to mark the anniversary suggests that the CIA was pretty well-informed about Soviet capabilities and intentions and that the launch of a satellite was expected, though nobody could guess at the timing. So President Eisenhower and the US government were not as shocked as the public, and they clearly worked on the principle that one should never waste a good crisis.

Why ‘free speech’ is always problematic

Nice New Yorker piece by Jill Lepore which starts with the Berkeley Free Speech movement of the 1960s and goes right up to the recent ‘kneeling’ protest by black NFL players. Concludes thus:

N.F.L. players insist that a stadium is a public square in which they have a right to exercise free speech. Their fight will rage on. But this fight began on college campuses, and it needs to be won there. All speech is not equal. Some things are true; some things are not. Figuring out how to tell the difference is the work of the university, which rests on a commitment to freedom of inquiry, an unflinching search for truth, and the fearless unmasking of error. But the university has obligations, too, to freedom of speech, whose premise, however idealized, is that, in a battle between truth and error, truth, in an open field, will always win. If the commitment to these difficult freedoms has sometimes flagged—and it has—it has just as often been renewed. Free speech is not a week or a place. It is a long and strenuous argument, as maddening as the past and as painful as the truth.

Quote of the Day

”Democracy is a pathetic belief in the collective wisdom of individual ignorance.”

H.L. Mencken

MadMen 2.0: The anthropology of the political

Gillian Tett, who is now the US Editor of the Financial Times, was trained as an anthropologist (which may be one reason why she spotted the fishy world of Collateral Debt Obligations and other dodgy derivatives before specialists who covered the banking sector). She had some interesting reflections in last weekend’s FT about data-driven campaigning in the 2016 Presidential election.

These were based on visits she had paid to the data-mavens of the Trump and Clinton campaigns during the election, and came away with some revealing insights into how they had taken completely different views on what constituted ‘politics’.

“Until now”, she writes,

”whenever pollsters have been asked to do research on politics, they have generally focussed on the things that modern western society labels ‘political’ — such as voter registration, policy surveys, party affiliation, voting records, and so on”. Broadly speaking, this is the way Clinton’s data team viewed the electorate. They had a vast database based on past voting patterns, voter registration and affiliations that was much more comprehensive than anything the Trump crowd had. “But”, says Tett, “this database was backwards-looking and limited to ‘politics’”. And Clinton’s data scientists thought that politics began and ended with ‘politics’.

The Trump crowd (which seems mainly to have been Cambridge Analytica, a strange outfit that is part hype-machine and part applied-psychometrics), took a completely different approach. As one of their executives told Tett,

”Enabling somebody and encouraging somebody to go out and vote on a wet Wednesday morning is no different in my mind to persuading and encouraging somebody to move from one toothpaste brand to another.” The task was, he said, “about understanding what message is relevant to that person at that time when they are in that particular mindset”.

This goes to the heart of what happened, in a way. It turned out that a sophisticated machine built for targeting finely-calibrated commercial messages to particular consumers was also suitable for delivering calibrated political messages to targeted voters. And I suppose that shouldn’t have come as such a shock. After all, when TV first appeared, all of the expertise and resources of Madison Avenue’s “hidden persuaders” was brought to bear on political campaigning. So what we’re seeing now is just Mad Men 2.0.