First drafts don’t have to be perfect. They just have to be written!

Monthly Archives: March 2017

Getting a handle on ‘fake news’ and the ‘post-truth’ stuff

I’m temperamentally suspicious of the “fake news” and “post-truth” discourse, for various reasons: it’s short on really hard evidence and detailed analysis; it attributes too much to non-mainstream media; it has an implicit nostalgia for a non-existent ‘truthful’ past; and it downplays the reasons why so many people in the UK and the US were willing to administer such a counterproductive (and perhaps self-defeating kick) to the (neo)liberal democratic system which has got us into this mess.

So it’s good to see more cautious, scholarly analyses emerging. Like this study by Yochai Benkler, Robert Faris, Hal Roberts, and Ethan Zuckerman.

Our own study of over 1.25 million stories published online between April 1, 2015 and Election Day shows that a right-wing media network anchored around Breitbart developed as a distinct and insulated media system, using social media as a backbone to transmit a hyper-partisan perspective to the world. This pro-Trump media sphere appears to have not only successfully set the agenda for the conservative media sphere, but also strongly influenced the broader media agenda, in particular coverage of Hillary Clinton.

While concerns about political and media polarization online are longstanding, our study suggests that polarization was asymmetric. Pro-Clinton audiences were highly attentive to traditional media outlets, which continued to be the most prominent outlets across the public sphere, alongside more left-oriented online sites. But pro-Trump audiences paid the majority of their attention to polarized outlets that have developed recently, many of them only since the 2008 election season.

Attacks on the integrity and professionalism of opposing media were also a central theme of right-wing media. Rather than “fake news” in the sense of wholly fabricated falsities, many of the most-shared stories can more accurately be understood as disinformation: the purposeful construction of true or partly true bits of information into a message that is, at its core, misleading. Over the course of the election, this turned the right-wing media system into an internally coherent, relatively insulated knowledge community, reinforcing the shared worldview of readers and shielding them from journalism that challenged it. The prevalence of such material has created an environment in which the President can tell supporters about events in Sweden that never happened, or a presidential advisor can reference a non-existent “Bowling Green massacre.”

Thee’s also a really interesting NBER paper by Hunt Allcott and Matthew Gentzkow on “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election. The Abstract summarises it thus:

We present new evidence on the role of false stories circulated on social media prior to the 2016 US presidential election. Drawing on audience data, archives of fact-checking websites, and results from a new online survey, we find: (i) social media was an important but not dominant source of news in the run-up to the election, with 14 percent of Americans calling social media their “most important” source of election news; (ii) of the known false news stories that appeared in the three months before the election, those favoring Trump were shared a total of 30 million times on Facebook, while those favoring Clinton were shared eight million times; (iii) the average American saw and remembered 0.92 pro-Trump fake news stories and 0.23 pro-Clinton fake news stories, with just over half of those who recalled seeing fake news stories believing them; (iv) for fake news to have changed the outcome of the election, a single fake article would need to have had the same persuasive effect as 36 television campaign ads.

Online advertising and the return of the Wanamaker problem

This morning’s Observer column:

And so the advertisers’ money, diverted from print and TV, cascaded into the coffers of Google and co. In 2012, Procter & Gamble announced that it would make $1bn in savings by targeting consumers through digital and social media. It has got to the point where, according to last week’s Financial Times, 2017 will be the year when advertisers spend more online than they do on TV.

Trebles all round, then? Not quite. It turns out that the advertising industry is beginning to smell a rat in this hi-tech nirvana. In a speech to the annual conference of the Internet Advertising Bureau in January, the Procter & Gamble boss, Marc Pritchard, said this: “We have seen an exponential increase in, well… crap. Craft or crap? Technology enables both and all too often the outcome has been more crappy advertising accompanied by even crappier viewing experiences… is it any wonder ad blockers are growing 40%?”

But the exponential growth in crap is not the biggest problem, he said. Much more worrying was the return of the Wanamaker problem: how many people are actually seeing these ads?

Extracting the moral signal from the populist noise

Apropos that earlier post, I was struck by this essay by danah boyd, and particularly by this passage:

If we don’t account for how people feel, we’re not going to achieve a more just world — we’re going to stoke the fires of a new cultural war as society becomes increasingly polarized.

The disconnect between statistical data and perception is astounding. I can’t help but shake my head when I listen to folks talk about how life is better today than it ever has been in history. They point to increased lifespan, new types of medicine, decline in infant mortality, and decline in poverty around the world. And they shake their heads in dismay about how people don’t seem to get it, don’t seem to get that today is better than yesterday. But perception isn’t about statistics. It’s about a feeling of security, a confidence in one’s ecosystem, a belief that through personal effort and God’s will, each day will be better than the last. That’s not where the vast majority of people are at right now. To the contrary, they’re feeling massively insecure, as though their world is very precarious.

I am deeply concerned that the people whose values and ideals I share are achieving solidarity through righteous rhetoric that also produces condescending and antagonistic norms. I don’t fully understand my discomfort, but I’m scared that what I’m seeing around me is making things worse.

There’s no technological fix for the mess we’re in

Amanda Hess has a thoughtful piece in the NYT about proposed tech fixes for the ‘filter bubble’ problem that has supposedly fractured democratic discourse in the US and elsewhere. She lists numerous well-meaning attempts — from browser plug-ins to iPhone apps — to use technology to help Internet users escape their personal bubbles.

It goes without saying that the motives behind these initiatives are good. (Ms Hess calls them “kumbaya vibes”.) The question is whether they really address the problem, which is rooted in human psychology — confirmation bias, homophily, etc.

The same social media networks that helped build the bubbles are now being framed as the solution, with just a few surface tweaks. On the internet, the “echo chambers” of old media — the ’90s buzzword for partisan talk radio shows and political paperbacks — have been amplified and automated. We no longer need to channel-surf to Fox News or MSNBC; unseen algorithms on Facebook learn to satisfy our existing preferences, so it doesn’t feel like we’re choosing an ideological filter at all.

But now, no entity is playing the filter bubble crisis more than Facebook itself. The company’s leader, Mark Zuckerberg, has published a manifesto of sorts, “Building Global Community,” which jockeys for Facebook to seize a central role in opening our minds by exposing us to new ideas.

Just last summer, the company was whistling a different tune. In a blog post called “Building a Better News Feed for You,” Facebook declared that the information it serves up is “subjective, personal, and unique — and defines the spirit of what we hope to achieve.” That all seemed harmless when the network was a site for reconnecting with old high school friends, but now Facebook is a major driver of news. (A Pew study from last year found that 62 percent of Americans get news on social media.) And as Mr. Trump rose, Facebook found itself assailed by critics blaming it for eroding the social fabric and contributing to the downfall of democracy. Facebook gave people what they wanted, they said, but not what they needed. So now it talks of building the “social infrastructure” for a “civically-engaged community.” Mr. Zuckerberg quoted Abraham Lincoln as inspiration for Facebook’s next phase.

Ms Hess also astutely points out that some of these ideas have partisan roots. The new tools for providing liberals with an insight into how other people think have a whiff of utilitarianism. The philosophy is that to win next time — and restore the old neoliberal order — we just need to know what the hoi-polloi are thinking. Which is a neat way of avoiding what really needs to happen, namely for ruling elites to hear the signal in the populist noise and accept the need to revise the way they think about politics and the world. As Carleigh Morgan, perceptively puts it, “exposure to new ideas and a commitment to listening are not the same”. Or, as Ms Hass puts it,

President Trump’s critics feel the practical need to break down these ideological cocoons, so they can win next time. Charlie Sykes, a former conservative radio talk show host who was blindsided by Mr. Trump’s win, now writes of the need to dismantle the “tribal bubble” of modern American politics, where citizens are informed through partisan media and bullied into submission by Twitter mobs. And Sam Altman, the president of the start-up incubator Y Combinator, recently set out from the liberal Silicon Valley and traveled across America to better understand the perspectives of Trump voters. His final question to them: “What would convince you not to vote for him again?”

It will be more difficult to entice Trump supporters to consider alternative perspectives, and not just because the president himself has declared the mainstream media the “opposition party.” As members of the winning team, Trump supporters have no urgent need to understand the other side.

Very good, thought-provoking piece. And repeat after me: there is no purely technological fix for the mess we’ve got ourselves into.

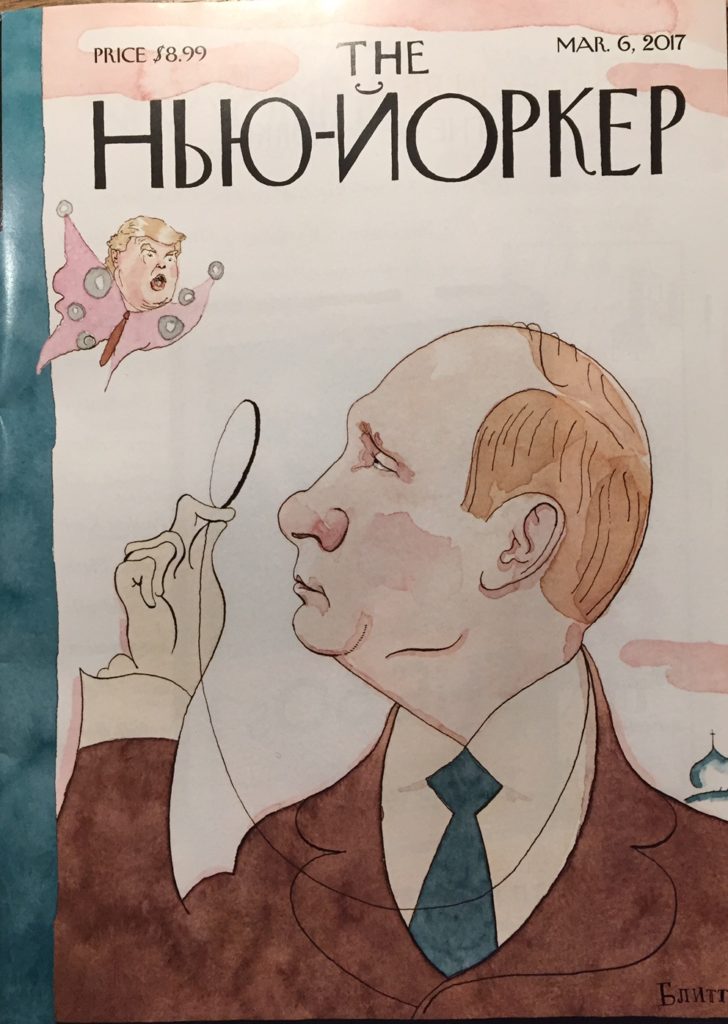

New Yorker, Moscow edition

Understanding Snapchat

Now that the IPO has valued Snap at $30B, perhaps the adult world will grasp that there’s something interesting here. Joel Stein has had a pretty good go at explaining it for them. Here’s the gist from his piece in Time:

Snapchat makes visual communication so frictionless that, according to Nielsen, it is used by roughly half of 18-to-34-year-olds, which is about seven times better than any TV network. Those who use it daily open the app 18 times a day for a total of nearly 30 minutes. Last fall, Snapchat passed Instagram and Facebook as the most important social network in the semiannual Taking Stock With Teens poll by the investment bank Piper Jaffray. Tweens used to count the days until they turned 13 so they could open a Facebook account; now they often don’t bother. And just as Facebook matured years ago, Snapchat is starting to be used by adults. The company says the app is now used by 158 million people daily, though that growth has slowed a bit lately.

Snapchat’s ethos is largely about the seemingly contrary values of control and fun: the company prospectus is one of the few in Wall Street history to use the word poop, employing it to explain just how often people use their smartphones. Snapchat gives users such tight control of their disappearing messages so that they feel safe taking an imperfect photo or video, and then layering information on top of it in the form of text, devil horns you can draw with your finger, a sticker that says “U Jelly?” or a filter that turns your face into a corncob that spits popcorn from your mouth when you talk. Snapchat is aware that most of our conversations are stupid.

But we want to keep our dumb conversations private. When Snapchat first launched, adults assumed it was merely a safe way for teens to send nude pictures, because adults are pervs. But what Spiegel understood is that teens wanted a safe way to express themselves.

Many teens are so worried about projecting perfection on Instagram that they create Finstagram (fake Instagram) profiles that only their friends know about. “Teens are very, very interested in safety, including something they call ’emotional safety,'” says San Diego State psychology professor Jean Twenge, author of the forthcoming iGen: The 10 Trends Shaping Today’s Young People–and the Nation. “They know on Snapchat, ‘If I make a funny face or use one of the filters and make myself look like a dog, it’s going to disappear. It won’t be something permanent my enemies at school can troll me about.'”

The Economist also has a kindly explanation for baffled oldies.

I’m a student – don’t stress me out

Lovely passage in David French’s review of Tyler Cowen’s new book — The Complacent Class:

This weekend, my wife and oldest daughter visited her first-choice college, the University of Tennessee. There was one curious moment in an otherwise wonderful weekend. The tour guide noted that the university was there to help students get through the trauma of exams. It brought in masseuses to massage away the stress. It rolls out a sheet of paper, passes out crayons, and lets the students express their rage against algebra. Oh, and it vowed to bring in puppies, so students could cuddle something cute to take the edge off their anxiety.