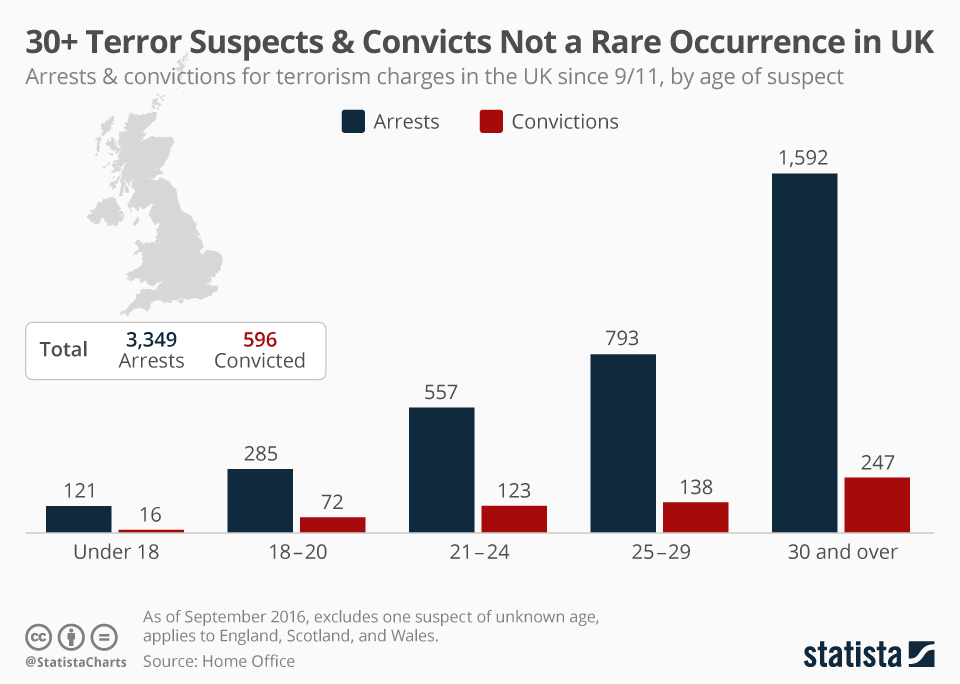

Interesting chart. Suggests that the ‘Prevent’ strategy might not make much of a difference.

Daily Archives: March 24, 2017

YouTube, dodgy content and the advertising business

There’s much hoo-hah about major corporations suddenly being scandalised by the discovery that their digital advertising appears alongside all kinds of objectionable YouTube videos. A sceptic might ask: what took them so long to realise this? One answer might be that most corporate executives don’t ever look at the kind of stuff on YouTube that kids watch. But, anyway, now they have discovered what’s been going on and they are reacting like scandalised Victorian spinsters who have just caught a glimpse of a naked ankle.

And they’re withdrawing their ads. As the NYT reports this morning:

But the technology underpinning YouTube’s advertising business has come under intense scrutiny in recent days, with AT&T, Johnson & Johnson and other deep-pocketed marketers announcing that they would pull their ads from the service. Their reason: The automated system in which ads are bought and placed online has too often resulted in brands appearing next to offensive material on YouTube such as hate speech.

On Thursday, the ride-sharing service Lyft became the latest example, removing their ads after they appeared next to videos from a racist skinhead group.

Google, sensing that this is going to turn into a PR nightmare, is responding in textbook fashion. Soothing noises, promises of technological fixes, plus gentle chiding of advertisers for apparently not being aware that they are not using the ‘tools’ that Google provides for decreasing the likelihood of their ads being seen in undesirable company.

The big question, of course, is whether this fuss is likely to do real damage to the company. Lots of investment analysts are crawling all over this. Here’s one assessment from RBC Capital Markets:

We built a very simple analysis based on the following assumptions: YT [YouTube] is roughly $14B of Revenue in 2017, and GDN [Google Display Network] is $4.8B (GOOG does not disclose so these are very rough ests); GDN pays 70% TAC; YT & GDN have roughly the same Net margins as our estimates for Alphabet as a whole (26.7% GAAP NI margins on Net Revenue). With this as a backdrop, a 10% hit to YT and GDN revenue in 2017 would be a 1.7% reduction to Net Revenue / GAAP EPS ($1.5B / $0.59) and a 2% hit would be 0.3% reduction ($309MM / $0.12).

If that’s right, this controversy is relatively small beer as far as Google is concerned. My conclusion: expect more soothing PR-speak and very little action.

The ideology behind the gig economy

Jia Tolentino has a very good piece in the New Yorker about the ideology that underpins the gig economy. The piece opens with the story of Mary, a Lyft driver in Chicago who kept accepting rides even though she was nine months pregnant – and even kept going when her contractions began!

In the end, it ended well. Mary had a customer who only needed a short ride, so she was able to drive herself to hospital after dropping him off. Once there, she gave birth to a baby girl — who appears on the company blog wearing a “Little Miss Lyft” onesie.

The point of the company blog post is to laud the spirit of workers like Mary. But, writes Tolentino,

It does require a fairly dystopian strain of doublethink for a company to celebrate how hard and how constantly its employees must work to make a living, given that these companies are themselves setting the terms. And yet this type of faux-inspirational tale has been appearing more lately, both in corporate advertising and in the news. Fiverr, an online freelance marketplace that promotes itself as being for “the lean entrepreneur”—as its name suggests, services advertised on Fiverr can be purchased for as low as five dollars—recently attracted ire for an ad campaign called “In Doers We Trust.” One ad, prominently displayed on some New York City subway cars, features a woman staring at the camera with a look of blank determination. “You eat a coffee for lunch,” the ad proclaims. “You follow through on your follow through. Sleep deprivation is your drug of choice. You might be a doer.”

Quite so. Lyft drivers in Chicago earn about $11 per trip.

Perhaps, as Lyft suggests, Mary kept accepting riders while experiencing contractions because “she was still a week away from her due date,” or “she didn’t believe she was going into labor yet.” Or maybe Mary kept accepting riders because the gig economy has further normalized the circumstances in which earning an extra eleven dollars can feel more important than seeking out the urgent medical care that these quasi-employers do not sponsor. In the other version of Mary’s story, she’s an unprotected worker in precarious circumstances.

Spot on.

The next war

Interesting snippet from Tom Ricks:

I interviewed Eric Schmidt of Google fame, who has been leading a civilian panel of technologists looking at how the Pentagon can better innovate. He said something I hadn’t heard before, which is that artificial intelligence helps the defense better than the offense. This is because AI always learns, and so constantly monitors patterns of incoming threats. This made me think that the next big war will be more like World War I (when the defense dominated) than World War II (when the offense did).