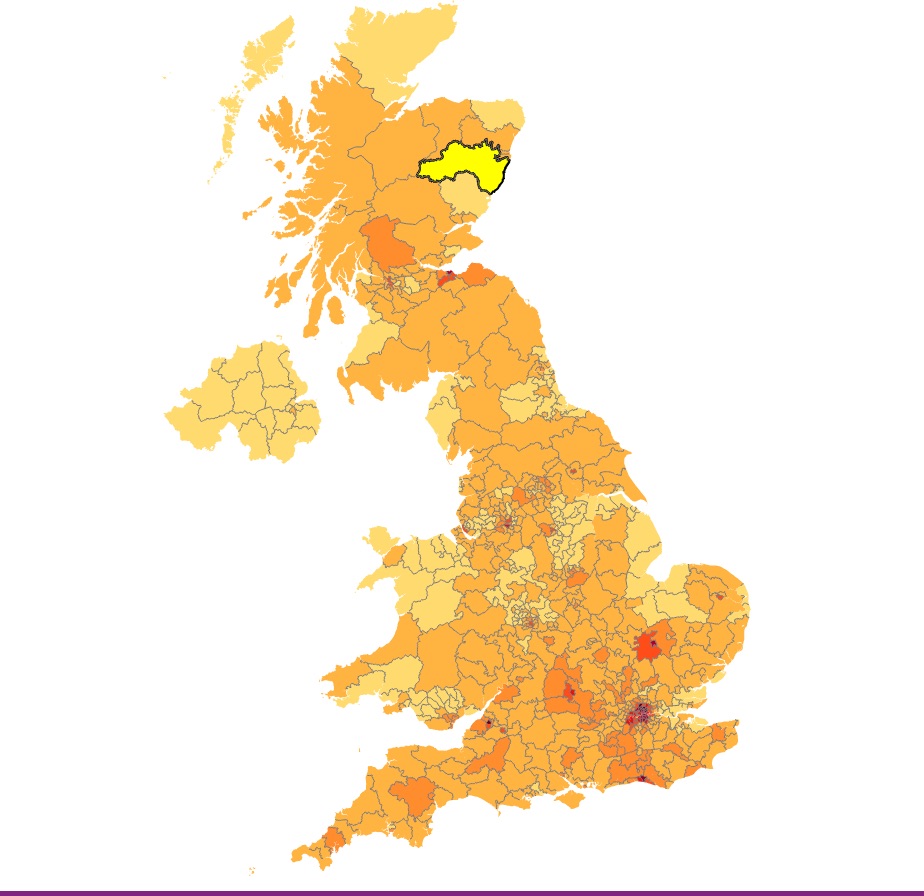

Here’s a neat idea — an online petition opposing the idea of a State Visit to the UK for Trump as pathetically proffered by Theresa May. Note that it doesn’t rule out the idea of Trump coming on an ordinary visit (for example for a NATO meeting) — just that the Queen shouldn’t be involved. As I write 1,438,415 people – plus me — have signed it. It’ll be 1.5m by the time you read this. The Petition site also has a nice ‘heat map’ showing the geolocation of the signatories.

Oh — and wouldn’t it be interesting to see if this heat map inversely correlates with the equivalent map for Brexit support? I’m sure some talented data-wrangler is already at work on this.

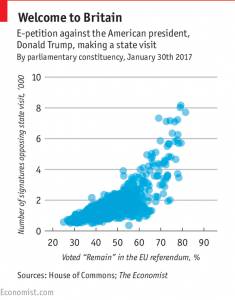

LATER They were! The Economist has published this correlation chart:

It also summarises the inferences one can draw from it.

This tells us several things. First, geographical patterns of opposition to Mr Trump in America may well be reflected in other countries too. Second, the demographics of his support and support for Brexit speak to similarities between the two phenomena (their “pull up the drawbridge” character in particular). Third, Britain’s divide over Brexit was not a one-off: the political behaviour of cosmopolitan places and nativist ones remains quite distinct. And fourth: there are many thousands of British people, many of them living in or near the capital, who may be minded to line the streets, protest and generally cause disruption when Mr Trump comes to London. He should not expect a warm welcome.

Many thanks to Philip Cunningham for spotting the chart.