Monthly Archives: December 2008

Remembering the Cruiser

Conor Cruise O’Brien, one of the most notable Irish intellectuals of my lifetime, was buried yesterday in Glasnevin cemetery, alongside his daughter Kate. He was 91.

Most of the obituaries failed to do him justice. The IHT/NYT one was perfunctory; the Guardian‘s (by Brian Fallon) was surprisingly unsatisfactory, given the author. The only obit I’ve read that came up to the mark was the one in the Times, which was masterful. (I suspect it was written by Roy Foster; at any rate, he’s the only one I could think of who has the requisite intellectual range.)

The Cruiser (as he was universally known in Ireland) first came to my attention when the ‘scandal’ of his divorce and remarriage (to the daughter of an Irish Cabinet minister) transfixed holy Catholic Ireland. My parents (devout Catholics) were scandalised. For my part, I was fascinated: who was this guy who could get people into such a lather? Later on, I got to know him slightly during the late 1970s when he was Editor-in-Chief of the Observer. I was not yet a columnist on the paper, but I was a regular contributor to the books pages, and so a frequent attendee in the nearby pubs behind New Printing House Square at the end of a working day. Cruiser was invariably also in attendance, drinking and arguing with anyone who caught his attention. It was in one of these sessions that he gave me a line which I’ve often used since in introducing myself to audiences. When he discovered that I was, like him, both an academic and a journalist, he remarked: “I see. You have a foot in both graves”.

At that time, no British paper had an Editor-in-Chief, though the role was commonplace in US newspaper groups. He was recruited by the American owners of the paper, the US oil company Atlantic Richfield, who felt that papers ought to have Editors-in-Chief and looked round for a really grand figure. Their gaze alighted on Conor. He demanded that the paper should rent a houseboat for him in Chelsea, where he lived from Tuesday to Friday, and then he flew back to Dublin to spend the weekend in his wonderful house atop Howth Hill overlooking Dublin Bay (where Leopold and Molly Bloom first made love).

He had an amazing life — well sketched in the Times obit. He began as a brilliant student, graduating from Trinity College with a double first. He was then, successively: a career civil servant; a diplomat; a high official of the UN carrying awesome responsibilities during an acute phase of the Cold War; a university Vice-Chancellor and, later, professor; a politician and Cabinet minister; a newspaper editor. And, for most of that time, a prolific author of memorable books and a newspaper columnist with a gift for controversy.

He had a remarkable intellectual range, producing first-rate historical scholarship on Parnell, terrific essays (e.g. Maria Cross on Catholic writers), a book on Gide, a play, a breathtaking memoir of his time as the UN representative in the Belgian Congo (To Katanga and Back), an insightful book about the United Nations, a great book on Edmund Burke, an intemperate book about Israel and a fascinating autobiography which was absolutely true to life in that it showed a character whose great gifts were balanced by great flaws.

In argument he was a real bruiser, especially when he had been drinking (which was often; I doubt that he ever went to bed sober). There was a real sense of danger when he was around. Simon Hoggart, who was then on the Observer, captured this in his column last Saturday:

He was a great toper, but made more sense when drunk than most of us while sober. His great theme, brilliantly expatiated, was the corrosive effect of Irish national mythology on the politics of the present day. I remember seven or so of us having a terrific session in the new El Vino’s in Blackfriars. The Cruiser had reached the stage that he had stopped drinking, but he always insisted on receiving another glass of red at each round.

My colleagues slipped away home before closing time, 8.15pm, and we were left alone. He solemnly drank the half dozen glasses in front of him, while distributing fascinating insights into the Northern Ireland problem as casually as crisps. Then he tottered to the door with me behind, waiting to catch him. Thank heavens, the orange light of a taxi loomed up, and I thought I had better find out where he was staying. “With my son,” he said gravely. “I know your son,” I said, “he’s a very nice bloke.”

Suddenly the red mist came down. He grabbed my lapels and stared at me, eyes blazing with anger. “I. Know. That!” he shouted, then gave a perfectly coherent address to the cabbie and climbed safely aboard.

But inside the bulldozer, there was a rapier. When the Cruiser was deeply embroiled in the Katangan fiasco, my friend Bill Kirkman, who was then the Africa correspondent for the Times, wrote a piece in which he said that one of the problems with the UN operation was that its staff included “too high a proportion of mediocrities”. Several days later, he was taken aback to receive a letter from the Cruiser suavely soliciting Bill’s advice as to “the correct proportion of mediocrities”.

He was such a paradoxical figure. On the one hand, the very model of a modern public intellectual in his willingness to speak out. He resigned from the Irish civil service, for example, in order to tell the Katangan story as he thought it should be told — something that did not endear him to several powerful governments, including that of Harold Macmillan. He was likewise courageous — and, ultimately, correct — in challenging the sentimental, myopic nationalism which characterised Irish policy towards the North until the 1980s. He saw through the cant of the Provisional IRA and its Sinn Fein ventriloquists, and he stiffened the resolve of the Coalition Government of which he was a member in its campaign against terrorism. And he excoriated Charlie Haughey as a political gangster long before it was popular or profitable to do so.

But on the debit side — as Roy Greenslade perceptively observed — the Cruiser regarded consistency as a quality suited only to lesser mortals. He spent several years early in his career, for example, pushing Irish nationalist propaganda — the kind of myopic nationalism he later excoriated. His hatred of Sinn Fein led him to oppose the policy which eventually led to the Good Friday Agreement and the eventual emergence of power-sharing in Northern Ireland. And his courageous stance in favour of intellectual freedom in Nkrumah’s Ghana was at odds with the intolerance towards nationalist views that he displayed when he wielded real political power in the Republic — or indeed with his persecution of the journalist Mary Holland when he was Editor-in-Chief of the Observer. His admiration for Israel was not matched by any sympathetic understanding of the Palestinian position. And so on.

So, great gifts and great flaws. But a genuinely big figure in Irish life. He’ll be missed.

LATER: I remembered something he said to me (also in a pub). I was asking him what he thought of the Observer and he said something to the effect that you could always tell a newspaper by its copy-takers. (In the pre-Internet age all newspapers had people who transcribed copy telephoned in by reporters. The Observer’s copy-takers were a breed apart — highly literate and often very erudite.) Cruiser said he first realised this when he was phoning in a column. “The atmosphere”, he dictated, “was redolent of fin de siecle Vienna… That’s French, spelled f-i-n-space-d-e-…”. At this point he was interrupted by the copy-taker. “I think you should assume, Dr O’Brien”, he said, “that a copy-taker on the Observer would know what the end of the century is in French.”

Sigh. Memories of a vanished age. Remind me to tell you about the Boer War sometime…

Dem fones, dem fones, dem eye-fones

Pure genius! Thanks to Charles Arthur for spotting it. Made my day!

Journalisted.com

This is an interesting development — a website funded by the Media Standards Trust which enables users to find out more about working British (er, and Irish) hacks. I’ve just run a search on myself (purely in the interests of research, you understand), and it comes up with the interesting factoid that I’ve written 59,700 words in 75 articles spread over 14 UK news websites since 2007. Not sure how accurate this is (and there is another John Naughton who writes about film and stag night videos for outfits like the Sunday Times and Radio Times so some of his stuff may be wrongly attributed to me — and vice versa). What is impressive, though, is that the site correctly identifies my most recent pieces. It also claims that I write more about Google than about anything else (with Microsoft a close second according to the tag cloud), which may well be true. But then those two companies are the biggest threat to our freedoms, so no apologies are called for.

En passant, Bobbie Johnson of the Guardian has just tweeted to say that Journalisted.com is claiming he’s written 250,000 words in the same time. Ratebuster!

Interesting Twitter application #257

From Steven Johnson.

A few months ago, I flew into London to give a talk at the Handheld Learning Conference, which had put me up at the Hoxton Hotel. I'd arrived late at night, and when I woke up, I realized that, for the first time in my life, I was waking up in London with no clear idea what neighborhood I was in. That seemed like precisely the kind of observation/query to share with the Twittersphere, and so I jotted down this tweet before heading out to find a coffee:

Waking up at the Hoxton Hotel in London — strangely unclear as to what neighborhood I'm actually in…

When I came back from coffee, I discovered, first, from a batch of Twitter replies that I was apparently in the neighborhood where half my London friends lived and worked. And then I noticed the envelope that had been placed on my desk. I opened it up, and it turned out to be a note from a producer who worked with Sir David Frost. They had noticed on Twitter that I was in London, and said they were very interested in having me talk with Sir David about Everything Bad Is Good For You for his show on English-language Al Jazeera.

Speed cameras and depravity

Hmmm…

Wonder if this is an urban legend.

High school students in Maryland are using speed cameras as a tool to fine innocent drivers in a game, according to the Montgomery County Sentinel newspaper. Because photo enforcement devices will automatically mail out a ticket to any registered vehicle owner based solely on a photograph of a license plate, any driver could receive a ticket if someone else creates a duplicate of his license plate and drives quickly past a speed camera. The private companies that mail out the tickets often do not bother to verify whether vehicle registration information for the accused vehicle matches the photographed vehicle.

In the UK, this is known as number plate cloning, where thieves will find the license information of a vehicle similar in appearance to the one they wish to drive. They will use that information to purchase a real license plate from a private vendor using the other vehicle's numbers. This allows the "cloned" vehicle to avoid all automated punishment systems. According to the Sentinel, two Rockville, Maryland high schools call their version of cloning the "speed camera pimping game."

A speed camera is located out in front of Wootton High School, providing a convenient location for generating the false tickets. Instead of purchasing license plates, students have ready access to laser printers that can create duplicate license plates using glossy paper using readily available fonts. For example, the state name of "Maryland" appears on plates in a font similar to Garamond Number 5 Swash Italic. Once the camera flashes, the driver can quickly pull over and remove the fake paper plate. The victim will receive a $40 ticket in the mail weeks later. According to the Sentinel, students at Richard Montgomery High School have also participated, although Montgomery County officials deny having seen any evidence of faked speed camera tickets.

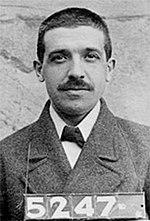

The original Mr Madoff

Meet Charles Ponzi, of the eponymous scheme. Cheery looking chap, isn’t he? The Times of July 28, 1920, reported thus:

An amazing “get-rich-quick” scheme, whereby Mr Charles Ponzi, a short time ago a relatively poor man, now estimates his wealth at upwards of £1,700,000, has attracted the attention of the public authorities of Boston.

The extraordinary feature of the case is that the authorities are not at all certain that Mr Ponzi’s operations are in any way illegal, and have only called a halt until his accounts, which run into millions of dollars, can be audited.

His arrest was quite a circus:

Mr Ponzi surrendered yesterday to the Federal authorities just in time to prevent his arrest by the State officials. It is said that the completed audit of Mr Ponzi’s affairs will show a deficit of at least £600,000. It is estimated that during the past six months he received from investors nearly £2,500,000, that in the fortnight since the run on his bank began he paid out about £1,500,000, and that his securities, realty, and other assets amount to perhaps £800,000.

The statement by the Federal auditor that Mr Ponzi’s accounts would show a deficit resulted in scenes almost approaching riot. The streets of South Boston were filled with hundreds of Poles, Italians, Greeks, and Lithuanians who had entrusted their savings to his charge.

This was before the foundation of the Palm Beach club, of course.

Robotic society

I particularly like the crack that most humans couldn’t pass a Turing Test. Also the observation that artificial intelligence makes people stupid.

The insanity of RAE

Those happy souls who live in the real world will not know that last Thursday saw the culmination of nonsense on stilts in the British university world — the release of the latest Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) results. In a nutshell, RAE is the extension of ‘targets’ and bean-counting to the world of ideas, and it’s a crazy system. In one major academic department I know, the most creative and original member of the department was excluded from the RAE by his colleagues because his pathbreaking work “didn’t fit the narrative” — i.e. the story being carefully crafted to impress the bean counters.

The mainstream media know nothing of this, however, so it’s really nice to see my Observer collleague, Simon Caulkin, turning his withering fire on it. He examines the consequences for universities of having to play the ‘targets’ game.

The first and most obvious of these is colossal bureaucracy. Government blithely assumes that management is weightless; but the direct cost of writing detailed specifications and special software, and assembling 1,100 panellists to scrutinise submissions from 50,000 individuals in 2,500 submissions, high as it already is, is dwarfed by the indirect ones – in particular, the huge and ongoing management overheads in the universities themselves. As with any target exercise, the RAE has developed into a costly arms race between the participants, who quickly figure out how to work the rules to their advantage, and regulators trying to plug the loopholes by adjusting and elaborating them.

The result is an RAE rulebook of staggering complexity on one side and, on the other, the generation of an army of university managers, consultants and PR spinners whose de facto purpose is not to teach, nor make intellectual discoveries, but to manage RAE scores. As in previous assessments, a lively transfer market in prolific researchers developed before the submission cut-off date at the end of 2007, while, under the urging of their managers, many university departments have been drafting and redrafting their submissions for the past three years.

Wapping comes to Wall Street

This morning’s Observer column.

You might think this is all a storm in an online teacup, but in fact it's a revealing case study of how our media ecosystem has changed. What happened is that reporters on a major newspaper got something wrong. Nothing unusual about that – and the concept of "network neutrality" is a slippery one if you're not a geek or a communications regulator. But within minutes of the article's publication, it was being picked up and critically dissected by bloggers all over the world. And much of the dissection was done soberly and intelligently, with commentators painstakingly explaining why Google's move into content-caching did not automatically signal a shift in the company's attitude to network neutrality. Lessig was able instantly to rebut the views attributed to him in the article.

Watching the discussion unfold online was like eavesdropping on a civilised and enlightening conversation. Browsing through it I thought: this is what the internet is like at its best – a powerful extension of what Jürgen Habermas once called "the public sphere".

And the Journal’s response? A snide little “roundup” on its website about critical responses to the article which – it observed – “has certainly gotten a rise out of the blogosphere”. Instead of an apology for a seriously flawed piece of journalism, it produced only a celebration of the outrage its errors had generated. Verily, the Sun has come to Wall Street.

Because my Observer column is limited to about 800 words, there’s a lot more I’d like to have said about this episode. It would have been nice, for example, to have been able to point to some of the more illuminating commentaries on the WSJ story. For example:

I could go on, but you will get the point. This was about as far as you can get from the LiveJournal-OMG-my-cat-has-just-been-sick media stereotyping of blogging. It was an illustration of something that has always been true — that the world is full of clever, thoughtful, well-informed people. What has changed is that we now have a medium in which they can talk to one another — and to newspaper reporters, of only the latter are prepared to participate in the conversation.

I’m searching for metaphors to capture what has happened. One image that comes to mind is that of a vast auditorium or sports arena which is packed to the rafters. In the centre is a stage with a very powerful public address system capable of generating tremendous amplification. Only a few people are allowed onto the stage to speak. When they do, everyone in the stadium can hear them. But they can’t hear the audience; or if they can it’s only as an undifferentiated roar. The performers cannot hear any individual voice.

That’s how it was when newspapers and broadcasters were in their prime. As someone who was first invited onto the stage in 1987 (and has been performing on it continuously ever since), I always felt that it was a privileged position, which carried with it commensurate responsibilities. No doubt many other journalists and columnists felt like that too. But as a group we took our privileged position for granted, and most of us didn’t notice that our technological advantage — the amplification provided by the mass-media publication machine — was eroding. Nor did many journalists notice that network technology — the ‘generative Internet’ in Jonathan Zittrain’s phrase — was busily providing members of the audience with their own global publishing machine. So suddenly we find ourselves in an arena where our amplifiers are losing power, and individual members of the audience can not only talk to one another, they can shout back at us.

But actually, most of the time they don’t want to shout. They want to talk. They think we’re wrong about something that they know about. Or they feel we haven’t done a subject justice, or maybe have missed a trick or even the point. The challenge for mainstream journalism now is whether its practitioners want to participate in the conversation that’s now possible. My complaint about the WSJ’s reaction to the blogosphere’s reaction is that it evinced a refusal to participate. The errors made by its reporters were serious but for the most part understandable; journalism is the rushed first draft of history and we all make mistakes. The tragedy was that the Journal saw the blogosphere’s criticism as a problem, when it fact it was an opportunity.