Neat, isn’t it. Details here.

Oh and here’s how to install a minimalist version of Linux on a flash drive.

Neat, isn’t it. Details here.

Oh and here’s how to install a minimalist version of Linux on a flash drive.

This is a serious question, not a rhetorical one. (I raised it tangentially in today’s Observer column.) It’s sparked by clear signs of stress in Redmond, with serious managerial restructuring and the announcement that Vista is going to be late — again. A few days ago, Steve Lohr and John Markoff asked the question in an article in the New York Times.

The company’s marathon effort to come up with the a new version of its desktop operating system, called Windows Vista, has repeatedly stalled. Last week, in the latest setback, Microsoft conceded that Vista would not be ready for consumers until January, missing the holiday sales season, to the chagrin of personal computer makers and electronics retailers — and those computer users eager to move up from Windows XP, a five-year-old product.

In those five years, Apple Computer has turned out four new versions of its Macintosh operating system, beating Microsoft to market with features that will be in Vista, like desktop search, advanced 3-D graphics and “widgets,” an array of small, single-purpose programs like news tickers, traffic reports and weather maps.

So what’s wrong with Microsoft? There is, after all, no shortage of smart software engineers working at the corporate campus in Redmond, Wash. The problem, it seems, is largely that Microsoft’s past success and its bundling strategy have become a weakness.

Lohr and Markoff say that the explanation is that Microsoft is hamstrung by its past success as a monopolist — that it has to make sure that its new operating system is “backwards compatible” with older versions of Microsoft software running on millions and millions of PCs.

I’m sure there’s something in this. But it’s not entirely convincing. After all, Apple has some of the same problems (albeit with a smaller consumer base and a more uniform hardware platform). So it was interesting to read Eric Raymond’s comment on the NYT article. He says that the authors have described only symptoms, not the underlying problem.

Closed-source software development has a scaling limit, a maximum complexity above which it collapses under its own weight.

Microsoft hit this wall six years ago, arguably longer; it’s why they’ve had to cancel several strategic projects in favor of superficial patches on the same old codebase. But it’s not a Microsoft-specific problem, just one that’s hitting them the worst because they’re the largest closed-source developer in existence. Management changes won’t address it any more than reshuffling the deck chairs could have kept the Titanic from sinking.

Apple has been able to ship four new versions in the last five years because its OS core is open-source code. Linux, entirely open-source, has bucketed along even faster. Open source evades the scaling limit by decentralizing development, replacing top-heavy monoliths with loosely-coupled peer networks at both the level of the code itself and the organizations that produce it.

You finger backward compatibility as a millstone around Microsoft’s neck, but experience with Linux and other open-source operating systems suggests this is not the real problem. Over the same six-year period Linux has maintained backwards binary compatibility as good as (arguably better than) that of Windows without bloating.

Microsoft’s problems cannot be fixed — indeed, they are doomed to get progressively worse — as long as they’re stuck to a development model premised on centralization, hierarchical control, and secrecy. Open-source operating systems will continue to gain at their expense for many of the same reasons free markets outcompeted centrally-planned economies.

The interesting question is whether we will ever see a Microsoft equivalent of glasnost and perestroika.

Excellent essay on the phoney rows about Wikipedia’s alleged inadequacies and limitations. Sample:

What pissed me off more was how the academic community pointed to this case and went “See! See! Wikipedia is terrible! We must protest it and stop it! It’s ruining our schools!” All of a sudden, i found myself defending Wikipedia to academics instead of reminding the pro-Wikipedians of its limitations in academia. I kept pointing out that they wouldn’t let students cite from encyclopedias either. I reminded folks that the answer is not to protest it, but to teach students how to read it and to understand its strengths and limitations. To actually TEACH students to interpret web material. I reminded academics that Wikipedia provides information to people who don’t have access to books and that mostly-good information is far better than none. Most importantly, i reminded academics that the vast majority of articles on Wikipedia are super solid and if they had a problem with them, they could fix them. Academics have a lot of knowledge, but all too often they forget that they are teachers and that there is great value in teaching the masses, not just the small number of students who will help their careers progress. Alas, public education has been devalued and information elitism is rampant in an age where we finally have the tools to make knowledge more accessible. Sad. (And one of the many things that is making me disillusioned with academia these days.) I found myself being the Wikipedia promoter because i found the extreme academic viewpoint to be just as egregious as the extreme Wikipedia viewpoint…

The piece goes on to quote Jimmy Wales’s wonderful defence of Wikipedia with an analogy about steak knives in restaurants.

From The Inquirer…

BIGGISH BLUE donned a Red Hat and said that it will not install Microsoft Vista into any of its corporate desktops and will continue its roll-out of Linux instead.

Speaking at a Linux Forum, IBM’s Open source and Linux technical sales bigwig Andreas Pleschek said that IBM has cancelled its contract with Microsoft as of October this year.

This means that Vista will not appear on any Big Blue desktops. Instead, from July IBM employees will begin using IBM Workplace on its brand spanking new, Red Hat-based platform.

Some users will remain on their old XP machines for a while, but none will be upgraded to Vista, said Pleschek.

Not clear if this is an IBM Germany decision on one that applies worldwide.

Wonderful piece in the Times by Gervase Markham, who looks after licensing for the Mozilla Foundation.

A little while ago, I received an e-mail from a lady in the Trading Standards department of a large northern town. They had encountered businesses which were selling copies of Firefox, and wanted to confirm that this was in violation of our licence agreements before taking action against them.

I wrote back, politely explaining the principles of copyleft – that the software was free, both as in speech and as in price, and that people copying and redistributing it was a feature, not a bug. I said that selling verbatim copies of Firefox on physical media was absolutely fine with us, and we would like her to return any confiscated CDs and allow us to continue with our plan for world domination (or words to that effect).

Unfortunately, this was not well received. Her reply was incredulous:

“I can’t believe that your company would allow people to make money from something that you allow people to have free access to. Is this really the case?” she asked.

“If Mozilla permit the sale of copied versions of its software, it makes it virtually impossible for us, from a practical point of view, to enforce UK anti-piracy legislation, as it is difficult for us to give general advice to businesses over what is/is not permitted.”

I felt somewhat unnerved at being held responsible for the disintegration of the UK anti-piracy system. Who would have thought giving away software could cause such difficulties?

Who indeed? Sometimes, it’s difficult to explain altruism to people. Sigh.

Thanks to Seb for the link.

My colleague, Seb Wills, has recently returned from Bangladesh, where he set up a multi-screen Ndiyo internet cafe (called a Community Information Centre) using mobile phone technology to provide the internet link. Given that the lack of connectivity is supposed to be a showstopper in developing countries, this is a really significant step forward. More details here.

From The Register. The really interesting thing is that the Linux they’re working on is allegedly based on the Ubuntu distro we use in the Ndiyo Project! Needless to say, it will be called Goobuntu.

I’m very interested in finding way of communicating the essence of important technological issues to lay audiences. The advantages of open source software are readily obvious to techies, but opaque to anyone who has never written a computer program.

So when I talk about open source software nowadays I find it helpful to talk about cooking recipes without mentioning computers at all. To communicate the importance of the ‘freedom to tinker’ that free software bestows on its users, for example, I invite people to ponder the absurdity of not being allowed to modify other people’s recipes for, say, Boeuf Bourgignon or fruit scones. I often make BB without using shallots, for example, and just chop standard onions into largish chunks. (It saves time and IMHO doesn’t materially affect the ultimate taste. And if a purist objects, I can always christen my modified recipe “Beef in red wine” and tell him to go to hell!)

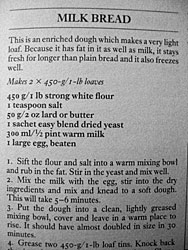

Similarly, to illustrate the difference between open source software and compiled binaries I compare Hovis bread-mix (“just add water”)

with a recipe for baking bread.

Most people grasp intuitively that the ‘open-source’ recipe gives you certain important freedoms that the ‘compiled’ bread-mix doesn’t.

Now comes an equally homely way of communicating to a lay audience what a news aggregator does.

A blogger compiled her own table of contents for several fashion magazines, mashing them up to make the one magazine she wanted (instead of the half-dozen ad-filled craptacular glossy anorexia advertisements that she had). If you’re struggling to explain the value of aggregators to offline people, this is a good place to start: magazines are often only 10% relevant to you, so what if you could extract the few good articles from a lot of mediocre magazines to get one really good magazine?

Insightful essay by David Weinberger. Excerpt:

The media literally can’t hear that humility, which reflects accurately the fluid and uneven quality of Wikipedia. The media — amplifying our general cultural assumptions — have come to expect knowledge to be coupled with arrogance : If you claim to know X, then you’ve also been claiming that you’re right and those who disagree are wrong. A leather-bound, published encyclopedia trades on this aura of utter rightness (as does a freebie e-newsletter, albeit it to a lesser degree). The media have a cognitive problem with a publisher of knowledge that modestly does not claim perfect reliability, does not back up that claim through a chain of credentialed individuals, and that does not believe the best way to assure the quality of knowledge is by disciplining individuals for their failures.