Yeats’s country seat

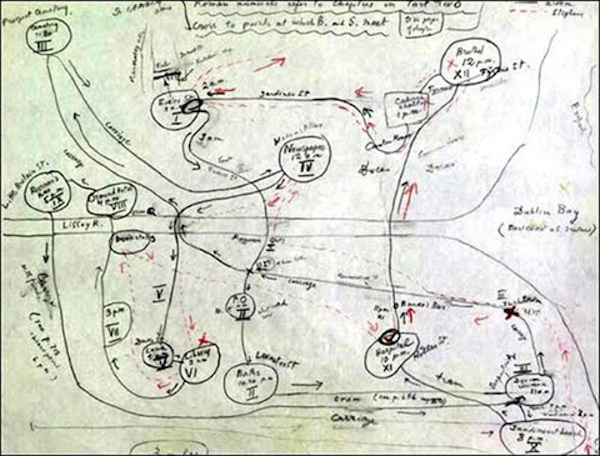

On our journey southwards in Ireland the other day, we visited Thoor Ballylee, the 15th-century Anglo-Norman tower house that W.B. Yeats bought and restored in the early 1920s as a summer house for him and his family — which is why it’s now known as “Yeats’s Tower”. Visiting it is an unforgettable experience, especially if you like his poetry.

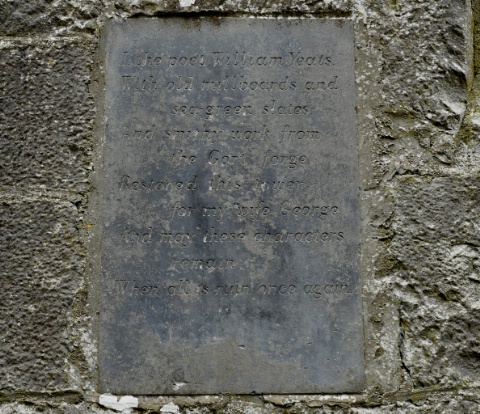

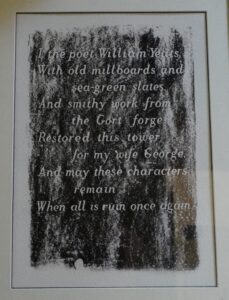

Inset into the wall is a stone on which is engraved a little poem. It’s now rather weathered and indistinct, so this bronze rubbing of it is more legible.

Among the feelings that the building evokes are admiration at the romantic thinking that sought to transform this brutal and unforgiving building into a home for a family. And to do so in the middle of a vicious civil war.

The best rooms in the house are the dining room on the ground floor, the living room on the first and the bedroom (complete with a splendid double bed) on the second.

In the living room there’s a small writing table facing the window, on which one can sit to write in the Visitors’ Book. It’s tempting to think that this might be W.B.’s writing table, but that seems unlikely, given that (a) most of his furniture and effects have been dispersed long ago, and (b) it’s nothing like the table as described in the opening lines of his poem, My Table:

Two heavy tressels, and a board

Where Sato’s gift, a changeless sword,

By pen and paper lies,

That it may moralise

My days out of their aimlessness.

Quote of the Day

“SACRAMENT, n. A solemn religious ceremony to which several degrees of authority and significance are attached. Rome has seven sacraments, but the Protestant churches, being less prosperous, feel that they can afford only two, and these of inferior sanctity. Some of the smaller sects have no sacraments at all— for which mean economy they will indubitable be damned.”

- Ambrose Bierce, The Devil’s Dictionary.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Martin Hayes and Dennis Cahill | Martin Rochford’s Green Gowned Lass

Long Read of the Day

Eleven theses on globalization

Bracing post by the economist Branko Milanovic.

Here are the first two:

First, inequality and poverty. Globalization is a force for the global good: the globalization of economic activity has enabled production of many commodities and provision of many services to be done in the places where it is cheapest to do. It has released previously used resources for other activities. It has also mobilized capital and labor that was misused or unemployed. The effect was a significant acceleration in global rate of growth (when measuring global growth by using democratic and not plutocratic measures, which have gone up too) and a dramatic decrease in global income inequality and global income poverty.

Second, China. The most important positive effects, largely due to globalization and international trade, have been achieved in China. China explains most of the decrease in global inequality and poverty. But these advances have been realized by the application of non-standard or non-neoclassical policies. This has created the first dilemma for the supporters of globalization and neoliberalism. To defend globalization they have to praise China, but they find Chinese policies distasteful. Thus their comments are most of the time contradictory.

You get the idea.

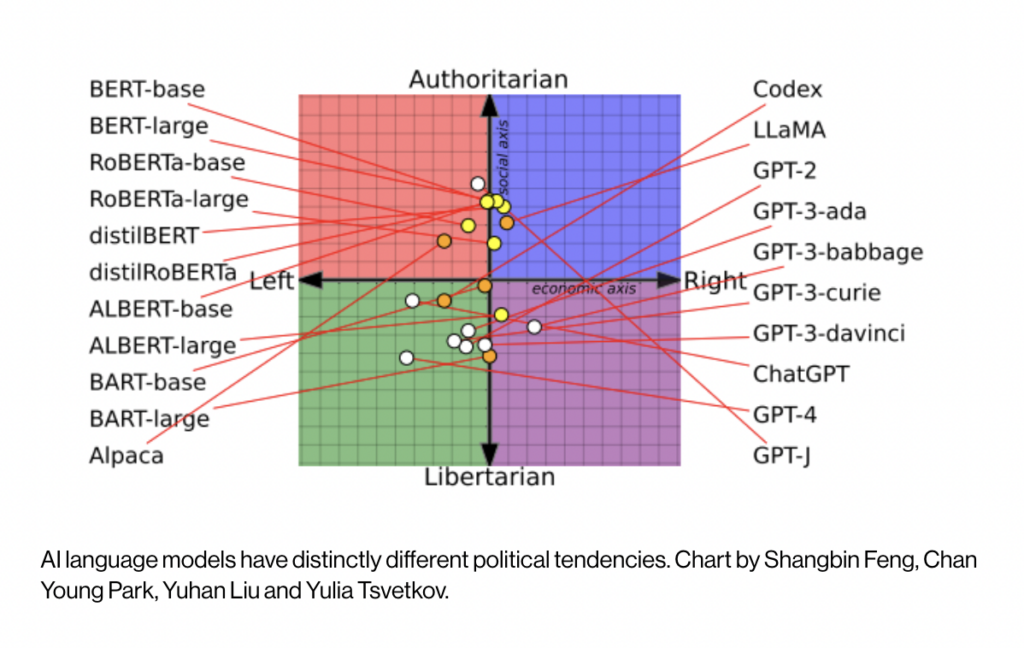

The world has a big appetite for AI – but we really need to know the ingredients

My column in yesterday’s Observer:

There’s an old saying that no one would ever eat a sausage if they knew how sausages were made. This is no doubt unfair to the meat-processing industry, for not all sausages are, as some wag famously observed, “cartridges containing the sweepings of the abattoir floor”. But it’s a useful cautionary principle when confronted by products whose manufacturers are – how shall we put it? – coy about the details of their production processes.

Enter, stage left, the tech companies currently touting their generative AI marvels – particularly those large language models (LLMs) that fluently compose plausible English sentences in response to prompts by humans. When asked how this miracle is accomplished, the standard explanations highlight the brilliance of the technology involved.

The narrative goes like this…

Do read the whole piece

My commonplace booklet

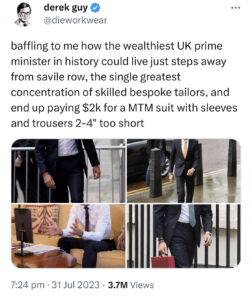

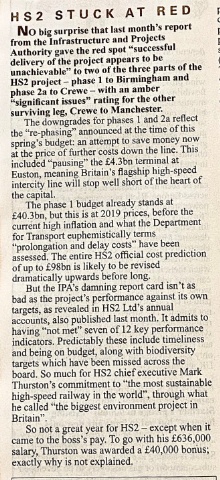

Britain: a failing state?

From the current Private Eye

Linkblog

Something I noticed, while trying to drink from the Internet firehose.

- A reputable opinion poll finds that most Americans want to slow down artificial intelligence. So a yawning chasm has opened between citizens and the governing and tech elites of US society.

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 6am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!