What’s this?

Outside Cambridge railway station yesterday.

Quote of the Day

”There is always one moment in childhood when the door opens and lets the future in.”

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Sharon Shannon | Galway Girl | Live at Cambridge Folk Festival

Link

Long Read of the Day

The Policy Paradox: The more obvious an idea is the less likely it will happen.

Sobering (and insightful) blog post by Sam Freedman.

I’ve been around for a while now and have occasionally found myself drifting into the cynicial “it’s been tried before” mode. So I’m trying to avoid it by taking a different approach. When I’m talking to a young think-tanker or political aide, whose enthusiam is not yet dimmed, I try not to dismiss ideas that have been doing the rounds for a while, but ask a different question: “given you’re not the first person to think of this why hasn’t it happened before?”

Just because something hasn’t worked, or has been blocked, in the past, it doesn’t mean it can’t work now. But it is important to understand the history and explain why it can be different this time.

The more of these discussions I have the more I have come to realise that there’s an odd paradox that applies to every policy area: the more obvious the idea, the less likely it is to happen. I don’t just mean obvious to me. There are plenty of policies that I personally – as a member of the dissolute liberal new elite – think are no brainers that are nevertheless hotly contested. No, these are ideas that everyone, bar perhaps a tiny ideological fringe, agree with, and that, at any of those panel events, will get a room full of appreciative nods, but nevertheless don’t happen…

It’s interesting, if sometimes dispiriting and when I was reading I kept thinking of Gramsci’s adage that what we need is “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will”. But, since pessimism can be disabling, maybe “realism of the intellect and optimism of the will” might be more useful.

There’s plenty of realism in this essay.

Thanks to Andrew Curry for alerting me to it.

Books, etc.

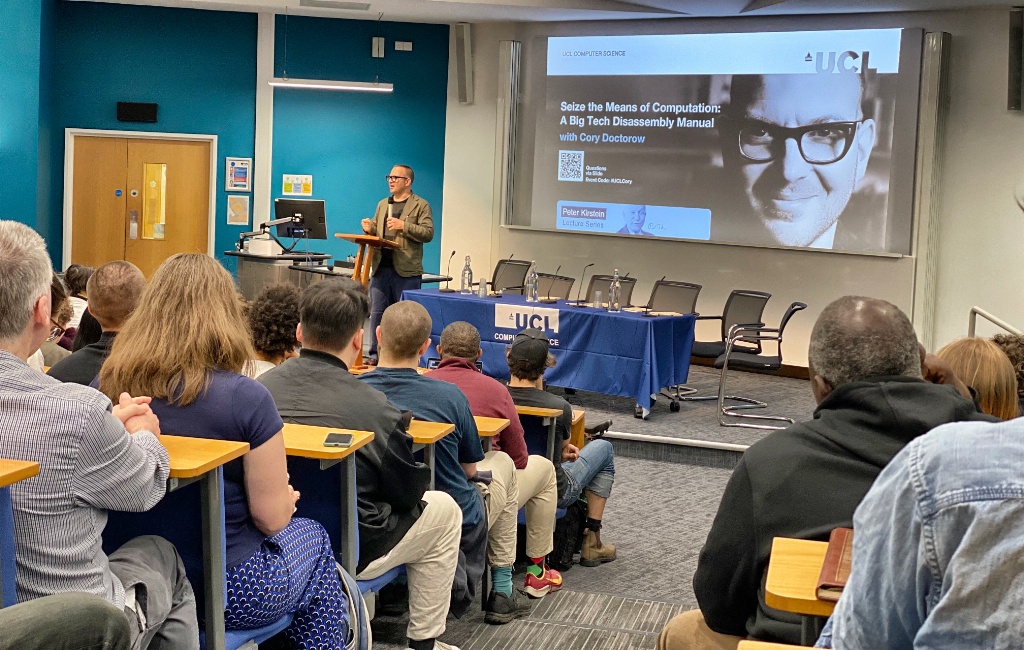

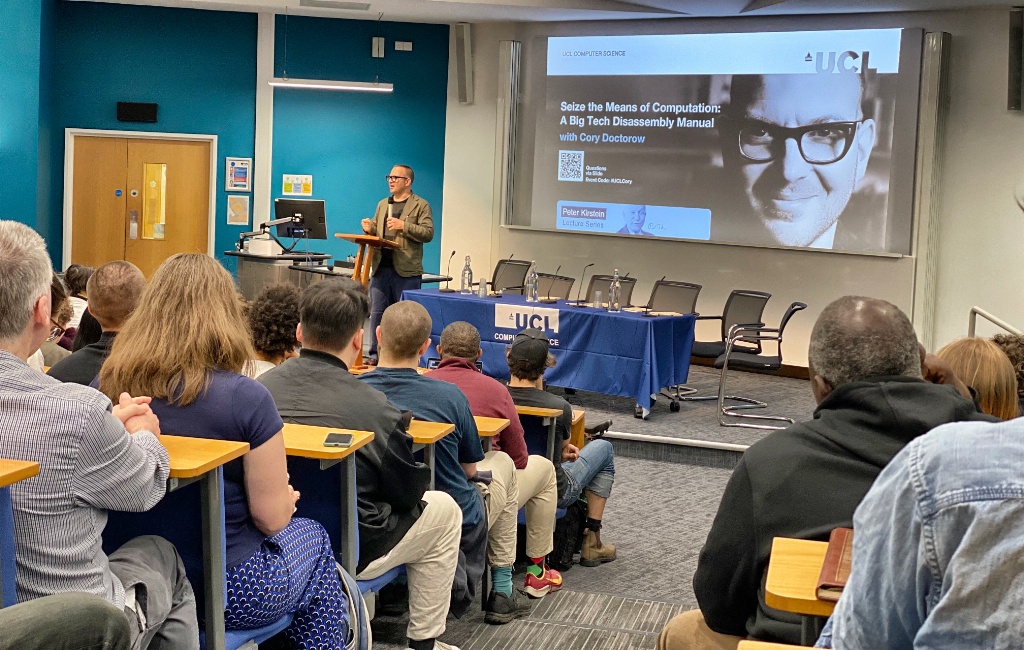

Cory Doctorow on a “Big Tech Dissassembly Manual”

Cory (Whom God Preserve) gave the Peter Kirstein Lecture in UCL yesterday. It was a typical Cory performance — which means that nobody slept at the back. The lecture theatre was packed and he outlined his ‘enshittification’ thesis of tech platforms with verve and wit and coruscating sarcasm. I like to think that I am critical of the tech industry, but in comparison to Cory I sound like a PR agent for Zuckerberg & Co.

I’ve also recently finished his first venture into mainstream thriller writing — Red Team Blues — and enjoyed it hugely. What’s special about it is the way it takes for granted the astonishing way in which tech (notably crypto) facilitates money-laundering, tax evasion and criminality on a cosmic scale. Henry Farrell wrote a perceptive review of it recently, and so now has his sister Maria — who was also at yesterday’s event, as evidenced below.

Cory is a truly extraordinary individual, the nearest thing we have to a one-man think-tank on the nature and pathologies of digital capitalism. More power to his elbow, as we say in Ireland.

My commonplace booklet

’Fire of Love’ trailer

This is a movie I’d like to see.

Errata

By now you will have gathered that in yesterday’s edition the number 10^60 (ten to the power of 60, which is as big a number as you are ever likely to contemplate), was rendered as 1060, which sounds like the state of England before the Norman Conquest!

This Blog is also available as a daily email. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!