Well, well. Facebook’s IPO Prospectus claims 845 million users, which is probably true. But it also claims that the number of “daily active users” is a whopping 483 million. Andrew Ross Sorkin of the New York Times found that number hard to swallow, so he went digging. And guess what? That number includes people like me who are registered Facebook users but almost never visit the site.

Facebook counts as “active” users who go to its Web site or its mobile site. But it also counts an entire other category of people who don’t click on facebook.com as “active users.” According to the company, a user is considered active if he or she “took an action to share content or activity with his or her Facebook friends or connections via a third-party Web site that is integrated with Facebook.”

Come again?

In other words, every time you press the “Like” button on NFL.com, for example, you’re an “active user” of Facebook. Perhaps you share a Twitter message on your Facebook account? That would make you an active Facebook user, too. Have you ever shared music on Spotify with a friend? You’re an active Facebook user. If you’ve logged into Huffington Post using your Facebook account and left a comment on the site — and your comment was automatically shared on Facebook — you, too, are an “active user” even though you’ve never actually spent any time on facebook.com.

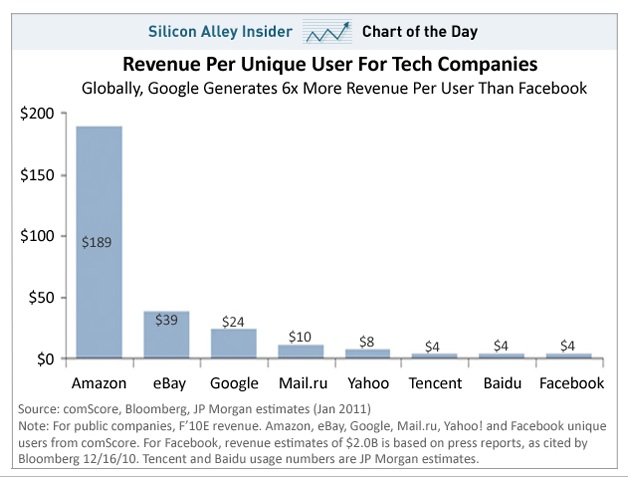

“Think of what this means in terms of monetizing their ‘daily users,’ ” Barry Ritholtz, the chief executive and director for equity research for Fusion IQ, wrote on his blog. “If they click a ‘like’ button but do not go to Facebook that day, they cannot be marketed to, they do not see any advertising, they cannot be sold any goods or services. All they did was take advantage of FB’s extensive infrastructure to tell their FB friends (who may or may not see what they did) that they liked something online. Period.”

Facebook appears to be using the term “active” as a euphemism for “engaged” rather than how many users are actually going to its site every month.

I count as an “active user” because I’ve arranged for my Twitter stream to be fed to my Facebook account as a set of status updates. But as a member of Facebook’s advertising ecosystem I’m a dead loss because I never see an ad.