Aleks Krotoski, by far the most elegant presenter at the Google Big Tent event yesterday.

Category Archives: Asides

Hypocrisy rules OK

What’s surprising about JP Morgan Chase’s admission that it ‘lost’ $2billion in the trading of complex financial derivatives is not that it happened but what it demonstrates about how our democracies have been captured by a banking system which continues to thumb its nose at legislators. For Jamie Dimon, the chief executive of JPMorgan Chase who had to reveal the cock-up in a call to analysts, was — and no doubt remains — a fierce opponent of tighter regulation of the banking system, and especially of any rule that might constrain banks from unduly risky behaviour. “What Mr. Dimon did not say”, observed the New York Times,

is that the loss also occurred because of a continued lack, nearly four years after the crisis, of rules and regulators up to the task of protecting taxpayers and the economy from the excesses of too big to fail banks; and, yes, of protecting the banks from their executives’ and traders’ destructive risk-taking.

The fact that JPMorgan’s loss — which Mr. Dimon has warned could “easily get worse” — is not enough to topple the bank, is not the point. What matters is that JPMorgan, like the nation’s other big banks, is still engaged in activities that can provoke catastrophic losses. If policy makers do not strengthen reform, then luck is the only thing preventing another meltdown.

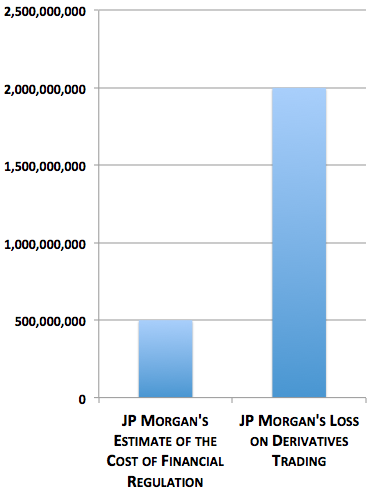

All of which brings to mind Mr Dimon’s ferocious opposition to the Dobb-Frank Act, which was the Congressional response to the banking catastrophe, compliance with which — he claimed — would cost his bank $400m-$600m annually. The Dobb-Frank Act was also the object of sustained ridicule by the Economist magazine in a long piece last February (which quoted Dimon’s estimate of the cost of compliance). The piece attacked what it portrayed as flaws in “the confused, bloated law passed in the aftermath of America’s financial crisis”, but failed to observe that one reason for the complexity of Dodd-Frank was the unconscionable complexity of the financial system that it was attempting to regulate.

The other thing that, strangely, escaped the notice of Economist is the need to make a cost-benefit assessment of initiatives like Dodd-Frank. Sure, the costs it imposes on banks are no doubt heavy; sure, it will give employment to lawyers and form-fillers. But what about the costs that the banking meltdown has inflicted on our societies (as some readers of the Economist pointed out in letters to the Editor the following week)?

But perhaps the most acute angle on the irony of JP Morgan Chase’s screw-up is provided by this chart by Derek Thompson of The Atlantic:

The NYT points out that the Dodd-Frank Act also calls for new rules on derivatives — including transparent trading and requirements for banks to back their trades with collateral and capital. If such rules were in place, JPMorgan’s trades could not have escaped notice by regulators and market participants. In the face of heavy lobbying, the derivatives’ rules have also been delayed or watered down. But guess what?

There are now several bills in the House, with bipartisan support, to weaken the Dodd-Frank law on derivatives. One of those would let the banks avoid Dodd-Frank regulation by conducting derivatives deals through foreign subsidiaries. The JPMorgan loss was incurred in its London office, which doesn’t lessen the effect here.

Finally — and needless to say — Mitt Romney has called for repealing the Dodd-Frank Act. Sometimes, one wonders if there is any intelligent life left on earth.

The Disruptive Innovator

It’s not often that one comes on books that change the way one thinks. Examples that have that kind of impact on me are Donald Schon’s The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action, Neil Postman’s The Disappearance of Childhood

, Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

and Howard Gardner’s Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences

.

And of course Clayton Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma, which has shaped my thinking about innovation ever since I read it many years ago. But although I knew his work, I knew very little about the man himself, which is why I found Larissa MacFarquhar’s New Yorker profile of him such riveting reading.

It appears in the May 14 issue and is, alas, behind the paywall, but the online summary gives a flavour of it.

In industry after industry, Christensen discovered, the new technologies that had brought the big, established companies to their knees weren’t better or more advanced—they were actually worse. The new products were low-end, dumb, shoddy, and in almost every way inferior. But the new products were usually cheaper and easier to use, and so people or companies who were not rich or sophisticated enough for the old ones started buying the new ones, and there were so many more of the regular people than there were of the rich, sophisticated people that the companies making the new products prospered. Christensen called these low-end products “disruptive technologies,” because, rather than sustaining technological progress toward better performance, they disrupted it.

It’s eerie how Christensen’s analysis still resonates. A few weeks ago, Kamal Munir from the Judge Business School gave a terrific talk in my Arcadia Seminar series at Cambridge University Library about his investigation of how Kodak fumbled the digital future. By any definition, Kodak was a great company which not only dominated its market, but had effectively created that market. And yet when the early digital cameras (like the Sony Mavica) arrived, the crappy technical quality of the images they produced was one of the factors that led Kodak to underestimate the threat that they would represent to its future. (Another factor was that the margins on digital photography were minuscule compared with the 70 per cent margins that Kodak was squeezing out of analog photography.)

And the innovation story goes on. We’re seeing it currently in the Higher Education business. Traditional universities are expensive and inefficient as teaching institutions, but most of them persist in believing that their USPs are such that scrappy online alternatives will never pose a serious threat. And it’s true that at the moment most online offerings are still pretty chaotic, variable and uncoordinated. But if Christensen’s analysis is correct, the challengers will eventually prove “good enough” for many customers (especially as the costs of traditional university courses continue to escalate) — with the result that he observed all those decades ago in industries like disk storage and steel-making. Caveat vendor.

Interestingly, MacFarquhar says that one of the people who first spotted Christensen’s work was Andy Grove:

One of the first C.E.O.s to understand the significance of Christensen’s idea was Andy Grove, the C.E.O. of Intel. Grove heard about it even before Christensen published his book, “The Innovator’s Dilemma,” in 1997. Intel brought out the Celeron chip, a cheap product that was ideal for the new low-end PCs, and within a year it had captured thirty-five per cent of the market. Soon afterward, Andy Grove stood up at the COMDEX trade show, in Las Vegas, holding a copy of “The Innovator’s Dilemma,” and told the audience that it was the most important book he’d read in ten years.

I’ve always thought that Grove was one of the most insightful CEOs of all time. He also understood the real significance of the Internet long before most people got it — as when he declared in 1999 that “in five years’ time all companies will be Internet companies or they won’t be companies at all”. What he meant was that the Net would become like the telephone or mains electricity: a utility that would transform the world in which everyone did business. Grove was much ridiculed for the declaration at the time. But he had the last laugh.

Trailblazers, road-builders and travellers (video)

Bertrand Russell’s Ten Commandments

1. Do not feel absolutely certain of anything.

2. Do not think it worth while to proceed by concealing evidence, for the evidence is sure to come to light.

3. Never try to discourage thinking for you are sure to succeed.

4. When you meet with opposition, even if it should be from your husband or your children, endeavor to overcome it by argument and not by authority, for a victory dependent upon authority is unreal and illusory.

5. Have no respect for the authority of others, for there are always contrary authorities to be found.

6. Do not use power to suppress opinions you think pernicious, for if you do the opinions will suppress you.

7. Do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric.

8. Find more pleasure in intelligent dissent than in passive agreement, for, if you value intelligence as you should, the former implies a deeper agreement than the latter.

9. Be scrupulously truthful, even if the truth is inconvenient, for it is more inconvenient when you try to conceal it.

10. Do not feel envious of the happiness of those who live in a fool’s paradise, for only a fool will think that it is happiness.

From the consistently terrific Brain Pickings.

Satire surfaces on Amazon

Sample of one of the spoof reviews on Amazon mentioned by Jamie Doward in his lovely Observer piece today.

I used to be a very successful insurance salesman at AIG. I had riches beyond belief: Faberge Eggs; Brut Aftershave, also by Faberge; a diamond encrusted Rolex; lime green Lamborghini; monogrammed slippers; a piano shaped toilet that once belonged to Liberace and a 16 ft pyramid of Ferrero Rocher chocolates. Some friends at the country club let me in on this secret that all the old money had canvas printed photos of Paul Ross, so I bought one at auction.

There was something wonderful and majestic about it, some people say the enigmatic smile is a knowing reference to his Merovingian ancestry. It hung for 3 years above the alabaster fireplace in my drawing room, replacing Munch’s Scream, which I borrowed from a friend who was also in the insurance business.

But over time there was something unsettling about the picture. At first it sounded like it emitted a high pitched, almost imperceptible, tone, like an old TV set. Then it started whispering things to me. After a while it started telling jokes and then giving me stock tips. Eventually it recommended I invest all my money with a guy called Bernie Madoff.

Now I have nothing, I get high by sucking anti-freeze from car windscreen washers, and even had to take public transport. My only possession is this picture of Paul Ross. It is my love, my life. He completes me.

Restores one’s faith in human nature.

The Succession

On Wednesday some of us went to a very enjoyable dinner at St Antony’s College, Oxford (which is Wolfson’s sister college). Wandering round the Combination Room afterwards I was struck by this juxtaposition of the bust of the founder of the college, Antonin Besse, and a lovely portrait by Henry Mee of its third Warden, Marrack Goulding.

Semi-infinite regress

Lucky winners celebrate missile lottery win

The problem for the Posh Boys: they’re not actually much good at running the country

My Observer colleague Andrew Rawnsley has a very perceptive column about Cameron and Osborne in the paper this morning.

Once asked, while in opposition, why he wanted to become prime minister, David Cameron replied: “Because I think I would be quite good at it”, one of the most self-revealing remarks he has ever made. Shortly after he moved into Number 10, someone inquired whether anything about the job had come as a surprise to him. Not really, he insouciantly replied: “It is much as I expected.” In his early period in office, that self-confidence served him rather well. He certainly looked quite good at being prime minister. He seemed to fit the part and fill the role. Broadly speaking, he performed like a man who knew what he was doing. That is one reason why his personal ratings were strikingly positive for a man presiding over grinding austerity and an unprecedented programme of cuts.

So you can get away with being “arrogant” as long as the voters think you have something to be arrogant about. You can also get away with being “posh” in politics. To most of the public, anyone who wears a good suit and swanks about in government limousines looks “posh” whether their schooldays were spent at Eton or Bash Street Comprehensive. There may even be some voters who think – or at least once thought – that an expensive education has its advantages as a preparation for running the country. Though David Cameron and George Osborne have always been sensitive on the subject, poshness wasn’t a really serious problem for them so long as they could persuade the public that they were in politics to serve the interests of the whole country, not just of their own class.

Rawnsley’s right: one of the things that has become obvious in the last few months is how amateurish these lads are. Their self-esteem is inversely proportional to their ability — a classic problem for toffs.

Maybe this is really beginning to dawn on the electorate. Currently Labour has a huge lead over the Tories in the polls. And that’s despite having Miliband like a millstone round the party’s neck.