People often thoughtlessly quote Keynes’s observation that “in the long run we are all dead” as a way of closing off an argument or a discussion. But, as Paul Krugman points out, the quotation is ripped completely out of its context. What Keynes actually wrote was: “But this long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead. Economists set themselves too easy, too useless a task if in tempestuous seasons they can only tell us that when the storm is long past the storm is flat again.”

Krugman points out that “Keynes’s point here is that economic models are incomplete, suspect, and only tell you where things will supposedly end up after a lot of time has passed. It’s an appeal for better analysis, not for ignoring the future.”

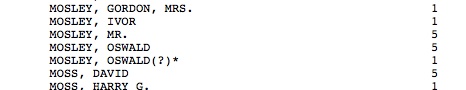

What’s interesting about this habit of misquoting Keynes is the way right-wingers use it as a way of ridiculing Keynes on the grounds that he was a homosexual. Brad DeLong highlights, for example, the way in which a succession of reactionaries — Joe Schumpeter, George Will, Daniel Johnson, Gertrude Himmelfarb and, yes, Niall Ferguson — have all used “in the long run we are all dead” as the basis for sneering homophobia. It is, one of them observed, only the kind of thing that “a childless homosexual” would have said.

LATER: To do him credit, Ferguson recanted and apologised. The statement on his website reads:

During a recent question-and-answer session at a conference in California, I made comments about John Maynard Keynes that were as stupid as they were insensitive.

I had been asked to comment on Keynes’s famous observation “In the long run we are all dead.” The point I had made in my presentation was that in the long run our children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren are alive, and will have to deal with the consequences of our economic actions.

But I should not have suggested – in an off-the-cuff response that was not part of my presentation – that Keynes was indifferent to the long run because he had no children, nor that he had no children because he was gay. This was doubly stupid. First, it is obvious that people who do not have children also care about future generations. Second, I had forgotten that Keynes’s wife Lydia miscarried.

My disagreements with Keynes’s economic philosophy have never had anything to do with his sexual orientation. It is simply false to suggest, as I did, that his approach to economic policy was inspired by any aspect of his personal life. As those who know me and my work are well aware, I detest all prejudice, sexual or otherwise.

My colleagues, students, and friends – straight and gay – have every right to be disappointed in me, as I am in myself. To them, and to everyone who heard my remarks at the conference or has read them since, I deeply and unreservedly apologize.